The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you without Digital Rights Management software (DRM) applied so that you can enjoy reading it on your personal devices. This e-book is for your personal use only. You may not print or post this e-book, or make this e-book publicly available in any way. You may not copy, reproduce or upload this e-book, other than to read it on one of your personal devices.

Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy .

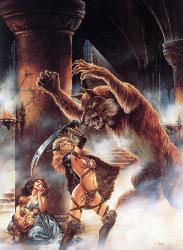

THE ULSTER CYCLE IS a large corpus of tales about the deeds of a legendary band of warriors led by Conchobor Mac Nessa who lived in the area now known as Ulster. They were originally called the Ulaidh but referred to themselves as the Rudhraighe, or rightful owners, and from this, the name of Conchobors house took its name: the Craeb Ruad of Emain Macha. The Craeb Ruad was only one of the three houses of Emain Macha, which included the Hostel of Kings at present-day Navan Fort, Co. Armagh, and Craeb Derg, where the skulls of enemies slain and other war trophies were stored. The exploits of these warriors, commonly called the Red Branch ( craeb: branch; ruad: red), make up the corpus of the Ulster Cycle.

The central tale of the Cycle is Tin B Cuailnge, or Cattle Raid of Cooley, of which a few recensions exist, the newest titled The Raid and translated by this author. The earliest surviving recension dates from roughly the eleventh century, but it appears to be a conflation of two previous texts that have their origin in the ninth century, with clarifying material added by the newest author. As near as we can reckon, it appears that the basic materialof this tale came from writings in the seventh century, although it seems to have had its genesis in the oral tradition, or bardic tradition, that dates back to the eighth century B.C.

The Ulster Cycle portrays a warrior-aristocracy that was organized along the lines of a heroic society and provides an excellent and authentic picture of the Iron Age Celtic culture.

Fled Bricrend, or Bricrius Feast, appears to be one of the oldest of the Ulster Cycle tales, dating back to the eighth century, and it survives today in several texts that have constantly been emended in order to explain some occurrences and parts of the tale that were common knowledge among the early Celts. Perhaps one of the more characteristic tales of the Ulster Cycle, Fled Bricrend is comprised of a mythic subtext, a heroic competition, and visits to and from the Otherworld that predate other stories in other cultures, suggesting that the Ulster Cycle may have been a major source of information for the compilers of such tales as Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and others.

Bricriu appears to be somewhat of an Irish Lki, a mischief-maker, although he seldom perpetrates any pranks that cause severe damage or death. He is more humanistic than Lki in that he appears to be misanthropic and does not seem to be capable of magic, although his threat to send the breasts of all women in Ireland banging together like empty bladders is taken most seriously by his peers. Unlike his Scandinavian counterpart, Bricriu cannot get out of difficulties through the use of wizardry or magic, but must depend upon his own wits. He suffers from bellyache, the gripe, and bitterness, all human conditions.

The central figure of the Ulster Cycle, however, even in Fled Bricrend, is not Bricriu, but Cchulainn, the Boy-Warrior, who became such a strong metaphor for the people of Ireland that today a statue of the mythical youth can be seen in the Dublin post office as a symbol of those who were forced to stand alone while attempting to achieve Irelands freedom from British rule. We cannot find any historical evidence that substantiates the existence of Cchulainn, although his king, Conchobor, does appear in records as the ruler of ancient Ulster sometime around 30 B.C.At the time, Ulster was a difficult land to travel in, what with dense fog and heavy undergrowth, almost surrounded by river and bog and mountains.

Although for the majority of Ireland in the seventh and eighth centuries, these stories were so familiar that simple reference to the main characters was enough to provide background for the listeners, this is not true today, for few people are aware of the Ulster Curse as it may be or what precipitated it, or of the birth of Cchulainn, or of the general cultural background that gives meaning to the story. Consequently, I have been forced to intrude into the text in order to add a few points for clarification in the following story.

Those who would like to further their studies of the Ulster Cycle may wish to consult other translations of the tales such as Joseph Dunns The Ancient Irish Epic Tale Tin B Calnge, London, 1914; Winifred Faradays The Cattle-Raid of Cualnge, London, 1904; Cecile ORahillys Tin B Calnge from the Book of Leinster, Dublin, 1967; Thomas Kinsellas The Tin, Oxford, 1969, and Lady Augusta Gregorys Cchulain of Muirthemne, London, 1902.

Of course it is much better if the reader can read the original work, which shows ancient life in all its raw sensuality. But with the recent rapid decline in the Celtic language, this is almost an impossibility. Even in Ireland, where the Ulster Cycle is part of the national heritage and tradition, barely one-tenth of the people are capable of reading the original text.

Much of early Irish literature has been lost, for it did not exist in a written form but was handed down over the centuries through the oral tradition: from singer to singer, seancha to seancha. Certain sections of the central story were undoubtedly altered by the singers or storytellers of the various provinces, who focused upon what was important to their particular people or clans. These snippets underwent constant alteration until the central story all but disappeared. In certain cases, as we can tell from a careful study of the Ulster Cycle, some stories undoubtedly disappeared, for great gaps exist between some of the stories, gaps that logic tells us probably were once filled by stories or minor episodes thatprovided a transition from one tale to the next.

Eventually these stories were written down in the seventh century by medieval monks in illuminated manuscripts, on parchment in some cases, then later transcribed into more formal units. Basically, the ancient Irish stories can be subdivided into four groups: those pertaining to the Tuatha D Danann, the Ulster Cycle, the Fenian Cycle, and what we may call a post-Fenian Cycle.

The Tuatha D Danann refers to the various tribes that supposedly traced their lineage from the goddess Anu, or Danu, a Mother Goddess associated with fertility celebrations. According to legend, the Tuatha came from four cities in the northern islands of GreeceFailias, Goirias, Findias, and Muiriasbringing with them their knowledge of the Druidic arts (a possible reference to the Eleusinian Mysteries), and defeated the Fir Bolg for control of Ireland. They were discovered by the Fomorians (sea-comers, or those who live under the sea), and the ensuing battle suggests a struggle between darkness (the Fomorians) and light ( Tuatha D Danann ), a common theme in stories from ancient cultures. The Tuatha are those who are commonly referred to as the gods of Ireland. According to legend, they came to Ireland from Greece, bringing with them the Lia Fail, a stone that utters a shriek at the inauguration of the rightful king; the invincible spear of Lugh; the deadly sword of Nuada; and the ever-plentiful cauldron of the Dagda, the Good God, or Father God, of Ireland. This story can be found in the account of the third invasion in The Book of Invasions (Lebor Gabala).