Foreword

The Holocaust was a set of events that engulfed an entire continent. The Nazi occupation of Europe pu r sued Jews from Greece to the Soviet Union. The survivors have been scattered around the globe. In recent years the memory of these events has become a global discourse there is a UN mandated remembrance day and the Holocaust has become a kind of moral touchstone which is held up as the central event of the twentieth century. As a consequence whenever one thinks of the Holocaust one inev itably thinks in terms of scale of six million dead, of journeys of thousands of miles. Th e rhetoric of Holocaust studies as attempts to understand th e Holocaust have become defined also emphasize the enormity of the events with which we are grappling, we are constantly reminded of the idea that the Holocaust is both unrepr e sentable and unimaginable. Part of this rhetoric is the idea that the Final Solution operated on an indu s trial scale , and that the concentration camps need to be understood as factories of death. Within this epic memory it is the camp at Auschwitz that provides much of the iconography both through contemporary images (the unmistakable tower at the entrance of Auschwitz-Birkenau for example) and the images b e queathed by the memorial museum, the apparently endless stacks of human hair, or the piles of shoes and suitcases.

Reading Chris Webb ' s book on Treblinka one is somewhat para doxically struck by the essential truth of that epic memory, but at the same time of some of its inherent distor tions by the degree to which Treblinka in some ways conforms and in some ways denies this epic memory. In Treblinka a meticulously constructed factory of death did emerge, where killing ultimately was the only function of the facility. This factory consumed, according to the numbers collected here , some 885 thousand lives. Such an o b servation is scarcely credible and one is tempted to simply throw up one ' s arms in despair and declare such events unimaginable.

Yet the detail brought together here, some of it for the first time in the English language, also provides a timely warning about surrendering to such rhetoric. This is not an unrepresentable or more precisely unimaginable horror. As Alan Confino argues in his recent Foundational Pasts , the Final Solution was and is imaginable precisely because it was imagined by its perpetrators. Chris Webb ' s reconstruction of Tr e blinka reminds us of this over and over again. This was a camp in which the technology of death was co n tinuously refined and made more efficient. While the end result might have been a cleaner process, it was not one in which the perpetrators were distanced from their crimes because the means of carrying out those crimes had been considered, reconsidered; imagined and re-imagined, over and over again.

One is also reminded in Webb ' s book of another, at times neglected reality of the Holocaust. Despite the implications of the epic memory I described, the Final Solution did not take place on another planet. Despite the desires of the perpetrat ors to keep their crimes secret the building of an imaginary train station at Treblinka being the most obvious indicator of that they were not. Although the reality of what was occurring in the death camps might have been obscured , these places were public spaces with which local populatio ns engaged in a variety of ways some of which are testified to here.

And despite the scale of the death toll, one is also reminded by Webb ' s book just how small places like Treblinka were and as such that the seismic events of the Holocaust were in many ways rather intimate too. Covering just a few hundred square meters , and with a largely identifiable staff, Treblinka was a place in which victims and perpetrators confronted one another repeatedly. This intimacy is reconstructed here and as such Treblinka emerges as very much representable. These are epic events, but they took place in spaces that are only too conceivable in the human imagination.

And it was of course because Treblinka was constructed on a small scale that in the aftermath of A k tion Reinhard t the camp could be dismantled and disguised. One of the consequences of this is that to visit Treblinka today is to visit a space in which there are no visible remains from the camp itself. Trebli n ka therefore stands, perhaps more than any other place, as representative of the void which the Final S o lution represents.

Yet it is thanks to works like Webb ' s and the scholarship that he represents here that we can know something of what happened there. We can hear the voices of surviving victims, and of course of the pe r petrators themselves. We can in that sense win a small victory over the Nazis ' efforts to destroy and to expunge Jews and Judaism from this world, and of course to expunge the memory of their own destru c tiveness. We can, thanks to collections of material like this, continue to proclaim that, in the words of Primo Levi, it has been. We can, however imperfectly, see into the void.

Professor Tom Lawson

Northumbria University

Authors ' Introduction

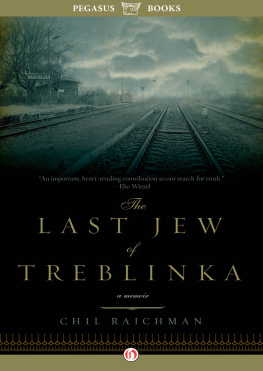

Treblinka Death Camp History, Biographies, Remembrance is the culmination of many years interest and research on the third and biggest of the three Aktion Reinhardt death camps in Nazi-occupied P o land, stimulated by the publication in 1967 of Jean-Francois Steiner ' s controversial book Treblinka, pu b lished in London by Weidenfeld & Nicholson and in New York by Simon & Schuster. An edition in Sl o vakian was published a year la ter by Obzor in Bratislava.

Within the pages of this book the history of the Treblinka camp is painstakingly reconstructed from its construction in early summer 1942 to its final liquidation in the autumn of 1943. During that short period of time, no more than fifteen months, approximately 900,000 Jews were deported to the camp from the big Polish ghettos of Warsaw and Biaystok, as well as from the districts of Lublin and Radom, and from as far afield as Austria, Germany, Greece, Macedonia, Salonika, a pa rt of former Czechoslovakia ( Reichs pro tektorat Bhmen / Mhren Bohemia and Moravia) and Vilna in the Reichs kommissariat Ostland (Lithuania). They were gassed and their bodies cremated on open air pyres.

Of these several hundred thousand victims deported to Treblinka, very few survived. The experiences of these few are recounted here partly in their own words in post-war testimony, and uniquely in the a u thors ' correspondence and personal interviews with the last survivors of Treblinka, Kalman Teigman, Eliahu Rosenberg, Samuel Willenberg, Pinchas Epstein, and Edi Weinstein. The debt owed to them and to their families for agreeing to meet and assist with our research, and in doing so reopening unimagin a bly painful memories, cannot be adequately repaid. This book is our modest attempt to honor both their courage and memory. At the time of writing (2014) only Samuel Willenberg is still alive.

There are several other people to whom we also owe a debt of thanks for their encouragement and i n valuable assistance in producing this book. First on the list is Michael Tregenza, the British historian based in Lublin, Poland, who has our deep gratitude for reading and copy-editing the entire manuscript, and for making invaluable suggestions and important additions to the text. His knowledge of Aktion Reinhardt and its personnel is second to none.

We would also like to warmly thank members of the ARC ( Aktion Reinhardt Camps) group who visited Treblinka in 2002 and subsequently established the website www.deathcamps.org. These include Michael Peters from Germany who undertook some sterling research on T4/ Treblinka personnel and Peter Laponder from South Africa, both of whom built models of the Treblinka death camp. Also from the ARC group, we wish to express our gratitude to Robert Kuwalek and Lukasz Biedka (Poland), Dr. Robin O ' Neil (UK), and the late Billy Rutherford (UK), another talented model-maker.