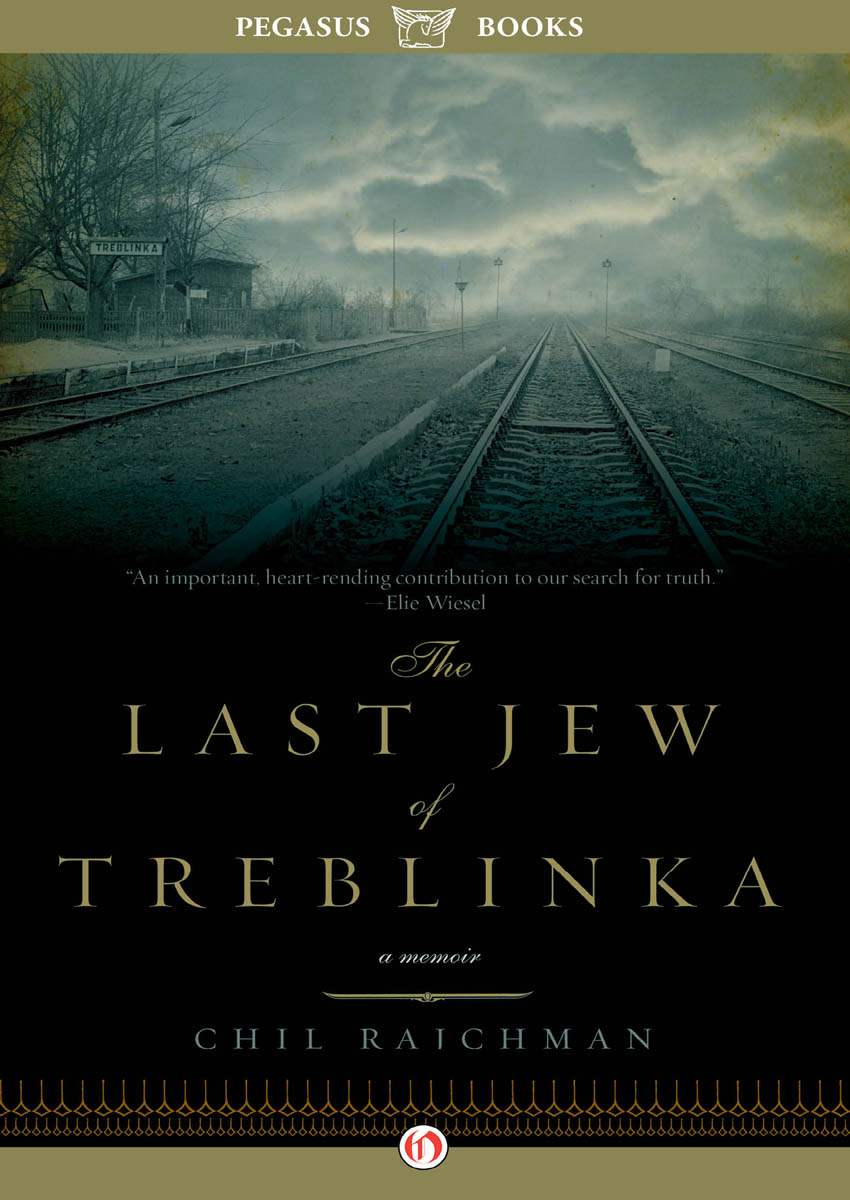

The

LAST JEW

of

TREBLINKA

A Survivors Memory

19421943

CHIL RAJCHMAN

Translated from the Yiddish by

Solon Beinfeld

PEGASUS BOOKS

NEW YORK

For all those to whom it was not possible to tell this tale.

Andrs, Daniel, Jos Rajchman

Preface

BY SAMUEL MOYN

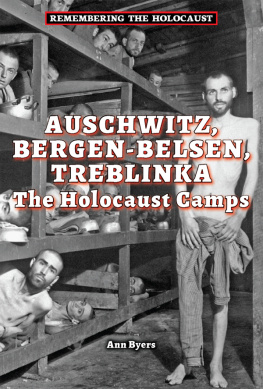

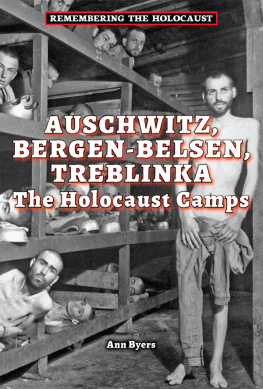

I N MID -A PRIL 1945 , A MERICAN GI S LIBERATED Buchenwald, while British soldiers marched, horrified, into Bergen-Belsen. There they found scenes of unimaginable suffering, men of bones and skin somehow standing on spindly legs, amidst piles of emaciated corpses. Celebrated journalists documented what must have seemed the nether pole of human depravity: the worst an inhuman regime could achieve. Even as thousands of typhus-stricken survivors died, witnesses to a liberation that came too late for them, Margaret Bourke-White took chilling photographs that captured the consequences of the Nazi designs, and a picture of evil was set. And yet, Treblinka was absent from this picture.

Chil Rajchmans memoir of that place lay in Yiddish manuscript for decades, and the very name Treblinka became widely known only decades after wars end. Yet Rajchman was witness to a very different reality, at a site thatunlike the concentration campsNazis had long since tried to wipe from the map. It was further east, in the territories the Red Army liberated, and where far more pitiless dynamics of killing were unleashed than the global audience of Belsen and Buchenwald could have imagined. The Nazi project of extermination reached its most terrible extremity in Treblinka and at the other industrial killing centers whose names were at first equally unfamiliar.

These were places very different than the Western concentration camps, which became lethal only in the last months of a war, as a failed regime lost its ability to feed its prisoners. In the eastern killing facilities, by contrast, the Nazi state did what it set out to do, after it chose the final solution of extermination. Unlike in the West, the victims in the east were dealt immediate extinction on arrival, and died as Jews targeted as Jews by the regime. Next to no one survived: compared to the scores of memoirs testifying to the concentration camps, which though terrible were generally not intended to kill, a paltry number could write of any experiences in the death camps. Only those few who, like Rajchman, were selected to operate the machinery of extinction in the Sonderkommando of the killing center, and not put to death themselves along the way or at the end, could tell what happened.

Along with a handful of other documents, Rajchmans astonishing memoirdrafted mostly in hiding before the Soviets reached Warsaw, where he had fled after his unlikely survival and escapeis one of the best descriptions of the Nazi project of extermination at its most spare and deadly. Indeed, the era can be known in its true horror only thanks to texts like this one.

I N CONTRAST TO THE W ESTERN CONCENTRATION CAMPS , which originated before World War II for a variety of Adolf Hitlers internal enemiescommunists and criminals were their main residents until the war and indeed during much of itthe extermination camps of the east arose in the heat of conflict on the eastern front. In the second half of 1941 the process of exterminating the Jews slowly shifted. Dominated immediately after the German invasion of the Soviet Union by mass shootings beyond the Molotov-Ribbentrop line, it now turned into a policy of constructing death factories behind it, as the triumphs of the invasion of the east in Operation Barbarossa slowed and a lightning victory came to seem out of reach.

Following Heinrich Himmlers orders, the SS began by setting up Chemno, in the Wartheland district of Greater Germany, and then Beec and Sobibr, across the border in the General Government, as the Nazis called their new colony made up of former Polish territories. Then Himmler ordered the erection of a new site, closer to Warsaw, also part of the General Government, and its largest city. Situated some fifty miles northeast of the city, on the Bug River, Treblinka was complete in June 1942. It became the centerpiece of Operation Reinhard, as the project of exterminating the Jews of the General Government came to be known, in honor of Reinhard Heydrich, a lieutenant of Himmlers who was assassinated that spring. In the end, 1.3 million Jews were killed as part of this policy, nearly 800,000 of them at Treblinka, in not much more than a year.

As if his destiny of living through so much death cuts him off from his prior existence, Rajchman tells nothing of his life before the grim railway cars bear him to this place in the memoirs opening lines. But more information is available in testimonies he later recorded for the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in 1988, and the USC Shoah Foundation Institute in 1994. Born Yechiel Meyer RajchmanChil for shorton June 14, 1914, in d, he fled east with a sister as the Germans invaded in 1939. Two years later, when with the Soviet campaign the final solution began in earnest, Rajchman found himself in the vicinity of Lublin, from where he was deported to Treblinka in the roundups that were intended erase a millennial Jewish presence from the area.

Arrival there means the immediate loss of his sister, along with all other women and children: the only work for which selection is possible at a death camp is for the handful of men needed to run the camp itself. Across the Molotov-Ribbentrop line, where hundreds of thousands of Jews were shot, mobile killing units took on the job of extermination; at Treblinka, as at the other death facilities, the logistics of destruction called for only a few dozen SS, some more Ukrainian assistants, and the Jews themselves. Rajchman refers his killers, indiscriminately, as murderers, with only a few singled out by name or nickname, notably Kurt Franz, the doll, famous for his dog, his vanity, and his cruelty. Rajchman knows the cremation specialist summoned for his expertise, almost certainly Herbert Floss, simply as the artist. And in passing, he mentions Ivan, dubbed the terrible, a sadistic brute whom Rajchman later believed he recognized in Ivan Demjanjuk, at whose American trial he testified.

R AJCHMAN S MEMOIR IS ABOVE ALL ELSE AN INCISIVE depiction of how the Nazis organized the destruction of millions of human beings and, indeed, reorganized and refined the process as time went on. As a worker, he moves from Treblinka 1 to Treblinka 2, sections of the killing center compartmentalized from each other by the gas chambers, to which arriving Jews are led along the Schlauch or corridor that the Germans euphemistically dubbed the road to heaven. Rajchman avoids that route somehow, and observes how man-made mass death is put into motion. If he knows on arrival what this place ispoignantly telling his sister not to bother with their bags on the trainhe learns the details of its professional evil only through harsh experience.

In brief, succeeding chapters, Rajchman tells of the infernal division of labor, through which the steps in the process of extermination are carefully apportioned, and whose shifting roles allow him to survive. He begins as a barber, shearing womens hair prior to their gassing, a fate many of the women he encounters clearly foresee, in one of the most affecting scenes Rajchman portrays in the narrative. Transferred to the secretive other zone of the camp, he carries bodies, asphyxiated by carbon monoxide generated from a diesel motor, often transformed beyond recognition, intertwined with one another, and repulsively swollen. Later, and for most of his time, Rajchman is made a so-called dentist, part of the crew of Jews charged with extracting gold from the teeth of corpses and searching the bodies for hidden valuables.