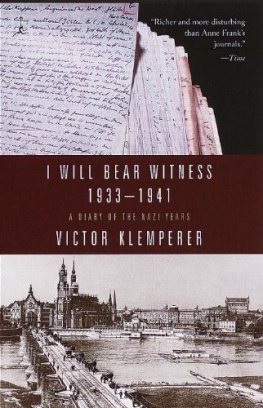

Critical acclaim for I Will Bear Witness

Together and separately, the two volumes form a stunning, engrossing, and magnificently human document, created by a shrewd and honest man during an insane and cataclysmic time. An eloquent and essential testament.

Chicago Tribune

Klemperers personal history of how the Third Reich month by month, sometimes week by week, accelerated its crusade against the Jews gives us as accurate a picture of Nazi trickery and brutality as we are likely to have. I Will Bear Witness is a report from the interior that tells the horrifying story of the evolving Nazi persecution with a concrete, vivid power that is, and I think will remain, unsurpassed. To read his almost day-by-day account is a hypnotic experience; the whole, hard to put down, is a true murder mysteryfrom the perspective of the victim.

P ETER G AY , The New York Times Book Review

Riveting and invaluable.

Arizona Republic

There is no better record of what it felt like to live through the war in Germany as a German Jew. I Will Bear Witness will take its place with the great human records of our time.

Newsday

What has been called one of the most remarkable documents to come out of the Second World War turns out to be one of the most compulsively readable books of the year.

The San Diego Union Tribune

The diary is his obsessionthe point is not to write history, but to provide evidence. That, of necessity, means confession. I Will Bear Witness is of great value to historians in their present debate as to how far ordinary Germans collaborated in the death of six million Jews. But it is even more precious as a story of love between two sixty-year-olds, both hypochondriacs who try each others nerves almost to the breaking point but who knowthis is the entry for March 18, 1945the main point after all is that for forty years we have so much loved one another.

P ENELOPE F ITZGERALD , The Wall Street Journal

Klemperers writing has a mesmerizing quality that draws readers on.

Denver Post

Richer and more profoundly disturbing than Anne Franks journals.

Time

This is color film of Nazi Germany after years of black and white. Klemperers diary deserves to rank alongside that of Anne Frank. It is certain to become not only the main primary source for historians of the Nazi period, but also an essential read for anyone who wishes to understand what it was like to be a Jew living in Germany in the 1930s.

P HILIP K ERR , The Sunday Times (London)

2001 Modern Library Paperback Edition

Translation, preface, and notes copyright 1999 by Martin Chalmers Discussion Guide copyright 2001 by Random House, Inc.

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

M ODERN L IBRARY and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

This translation was originally published in Great Britain by Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, and in the United States by Random House, Inc., New York, in 1999.

First published in Germany under the title Ich will Zeugnis ablegen bis zum letzten: Tagebcher 19331945 von Victor Klemperer.

Copyright Aufbau-Verlag GmbH, Berlin, 1995.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Klemperer, Victor.

[Ich will Zeugnis ablegen bis zum letzten. English]

I will bear witness: the diaries of Victor Klemperer.

p. cm.

Contents: [1]. 1933-1941.

ISBN 0-375-75697-3 ([1]: alk. paper)

1. Klemperer, Victor, 1881-1960Diaries.

2. French teachersGermanyDiaries. 3. PhilologistsGermanyDiaries. 4. GermanyHistory19331945Sources. I. Title. PC2064.K5A3 1998 943.086092dc21

[B] 98-15429

Modern Library website address: www.modernlibrary.com

eBook design adapted from printed book design by Mercedes Everett

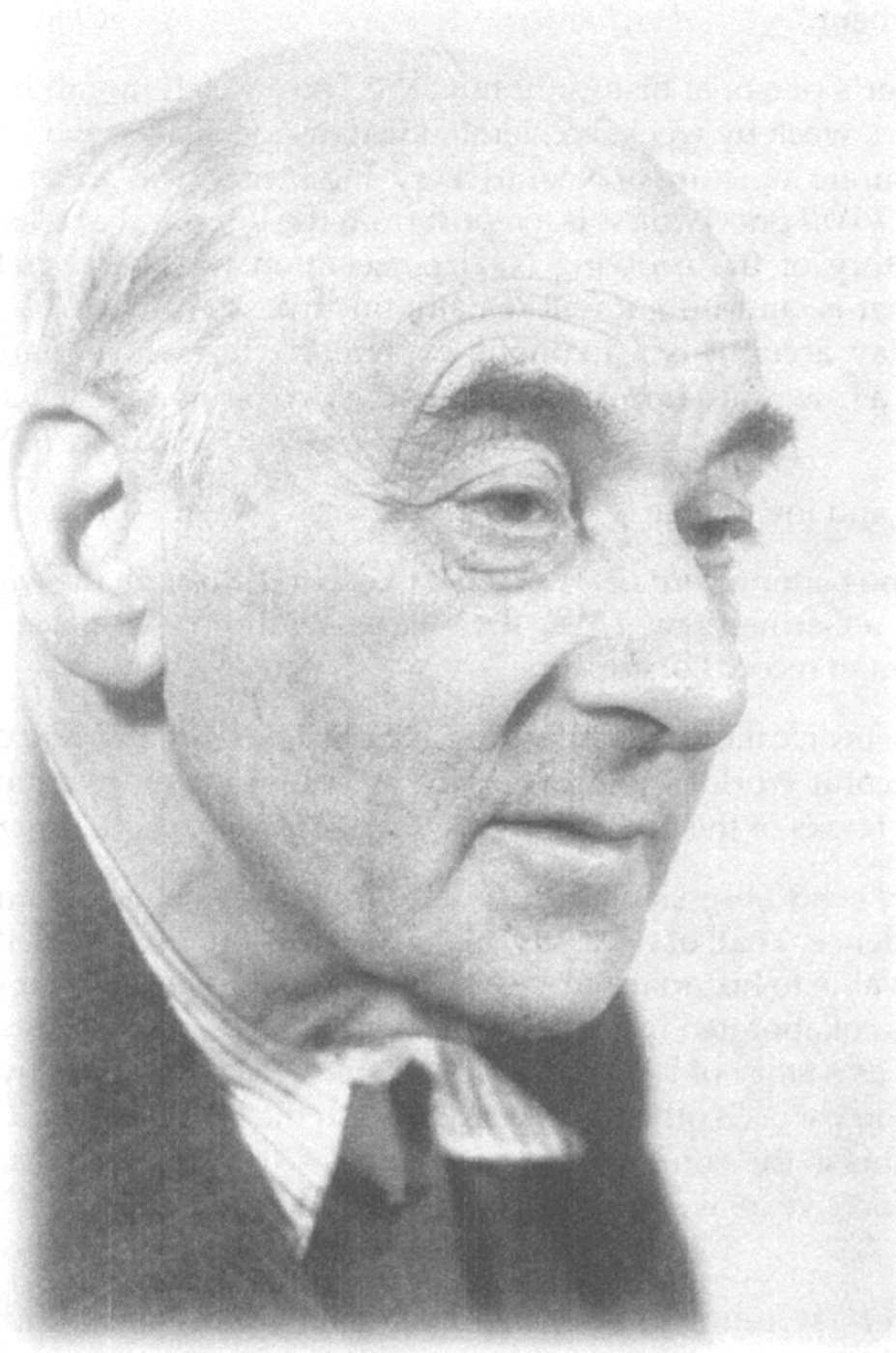

Frontispiece photograph of Victor Klemperer by Eva Kemlein, Berlin.

Photograph on p. vi Aufbau-Verlag GmbH.

eBook ISBN9780399589089

v4.1

a

I shall go on writing. That is my heroism.

I will bear witness, precise witness!

May 27, 1942

Eva and Victor Klemperer, c. 1940.

PREFACE

but I want to tell that he was a hero. He could not say three sentences without talking about his fear, but I want to tell of his courage.

Jurek Becker, Jakob the Liar

I

On New Years Eve 1941, Victor Klemperer gave a little speech to the remaining occupants of the Jews House at 15b Caspar David Friedrich Strasse in Dresden. It had been, he said, our most dreadful year, dreadful because of our own real experience, more dreadful because of the constant state of threat, most dreadful of all because of what we saw others suffering (deportation, murder)but, he concluded, there were grounds for optimism. The regime, he implied, was close to collapse, the guilty would receive just punishment.

As we now know, and the diarist Victor Klemperer was soon to discover, the worst was very far from over. The German advance after the surprise attack on the Soviet Union on June 22, 1941, had created the conditions for a final solution of the Jewish question by extermination. While the Jewish population of the newly occupied territories was massacred, the Jews of Germany and of the territories under German control were to be deported eastward and, together with the Jews of Poland, murdered immediately or starved and worked to death. The year 1942 would be, in Raul Hilbergs words, the most lethalin Jewish history.

At the end of 1941, Klemperer was still unaware of the massacres taking place behind the German front. The extent of his knowledge was summed up in a diary entry of October 25, 1941: Ever more shocking reports about deportation of Jews to Poland. They have to leave almost literally naked and penniless. Thousands from Berlin to Lodz. Dependent on rumor and secondhand reports of foreign broadcasts, Klemperer was only dimly able to discern the scope and radicalism of the Nazis plans and actions. The repercussions of the plan of genocide, however, were soon to be felt in Dresden.

On January 13, 1942, Paul Kreidl, a fellow resident of the Jews House where Klemperer lives, passes on a rumorbut it is very credible and comes from various sourcesevacuated Jews were shot in Riga, in groups, as they left the train. On the fifteenth, the first evacuation from Dresden is announced. The Zeiss-Ikon plant, in which a large number of the remaining Jews in the city work as forced labor, manages to retain its Jewish workers. Nevertheless, on January 21, 224 Jews from Dresden and nearby towns, including Paul Kreidl, are transported to the Riga ghetto.