Critical acclaim for I Will Bear Witness

Richer and more profoundly disturbing than Anne Franks journals.

Time

To read his almost day-by-day account is a hypnotic experience; the whole, hard to put down, is a true murder mysteryfrom the perspective of the victim. Klemperer [writes] with a vivid power that is, and I think will remain, unsurpassed.

P ETER G AY , The New York Times

Few readers will fail to be moved, as I wasultimately to the point of tears.

N IALL F ERGUSON , The Sunday Telegraph

Has the immediacy and poignancy of unedited notes written in the thick of experience. Extraordinary. One of the shrewdest and most meticulous observers of life under the Nazi regime.

The New Republic

This is history rawfull of shrewd observations on the nature of the Nazi regime and the quality of the response of the German people. An extraordinary and important event.

The New York Times

This is color film of Nazi Germany after years of black and white. Klemperers diary deserves to rank alongside that of Anne Frank. It is certain to become not only the main primary source for historians of the Nazi period, but also an essential read for anyone who wishes to understand what it was like to be a Jew living in Germany in the 1930s.

P HILIP K ERR , The Sunday Times (London)

Exceptional. Klemperers uniquely vivid voice deserves to be heard in the current debates surrounding Daniel Jonah Goldhagens wholesale indictment of ordinary Germans.

The Times Literary Supplement

The best written, most evocative, most observant record of daily life in the Third Reich.

A MOS E LON , The New York Times Magazine

The most extraordinary German witness of Nazism that has yet come to lightKlempererdemonstrates that reason is not only a quality of mindin his case a deeply moral perceptionbut also a cultural tradition of enormous value.

V ERLYN K LINKENBORG , The New York Times

1999 Modern Library Paperback Edition

Translation, preface, and notes copyright 1998 by Martin Chalmers

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Modern Library and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

This translation was originally published in Great Britain by Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, and in the United States by Random House, Inc., New York, in 1998.

First published in Germany under the title Ich will Zeugnis ablegen bis zum letzten: Tagebcher 19331945 von Victor Klemperer. Copyright Aufbau-Verlag GmbH, Berlin, 1995.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Klemperer, Victor.

[Ich will Zeugnis ablegen bis zum letzten. English]

I will bear witness: the diaries of Victor Klemperer.

p. cm.

Contents: [1]. 19331941.

ISBN 0-375-75378-8 [1]

1. Klemperer, Victor, 18811960Diaries.

2. French teachersGermanyDiaries. 3. PhilologistsGermanyDiaries. 4. GermanyHistory19331945Sources. I. Title.

PC2064.K5A31998

943.086092dc21

[B]9815429

eBook ISBN9780399589072

Modern Library website address: www.modernlibrary.com

eBook design adapted from printed book design Mercedes Everett

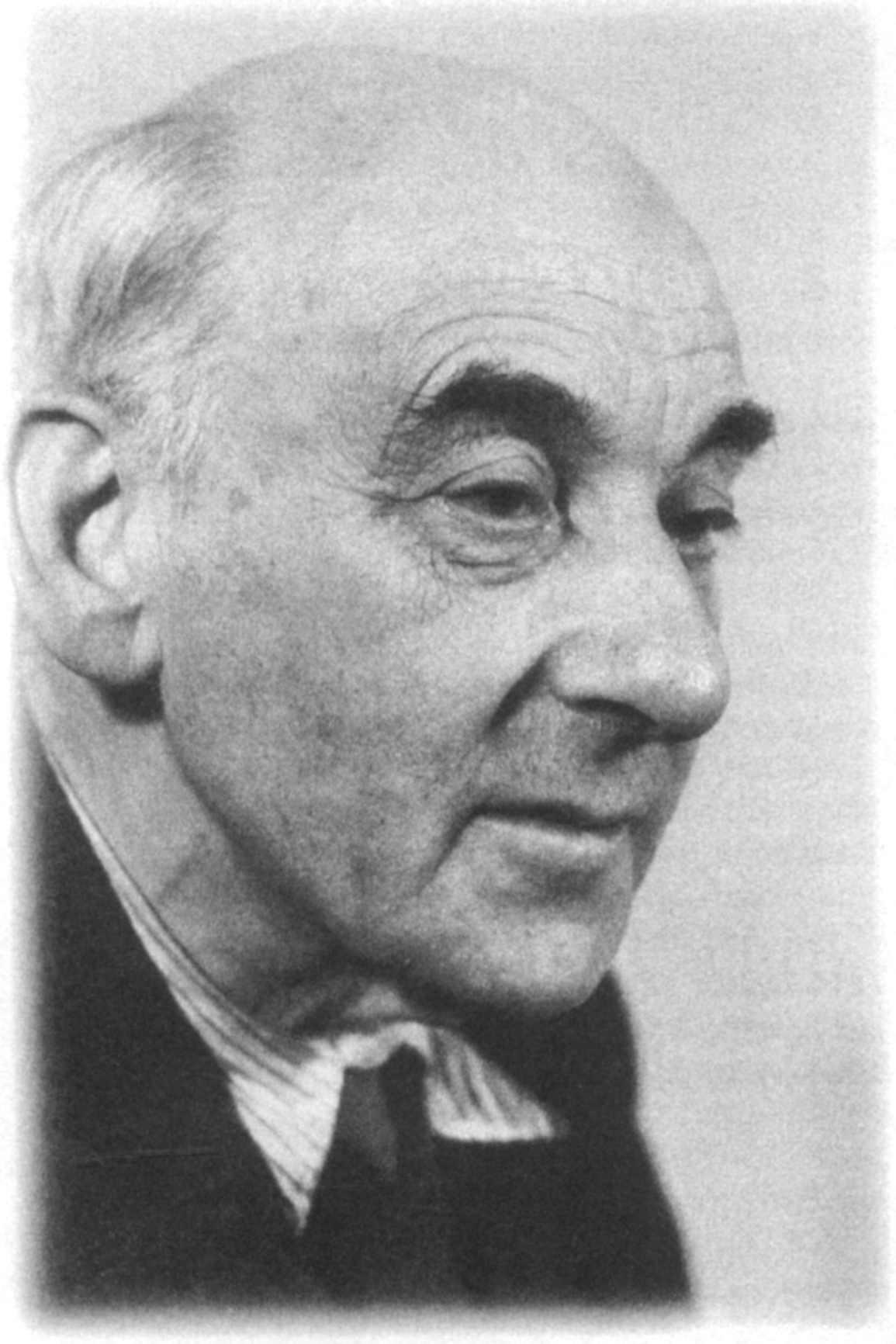

Frontispiece photograph of Victor Klemperer by Eva Kemlein, Berlin.

Photograph on Aufbau-Verlag GmbH.

v4.1

a

I shall go on writing. That is my heroism.

I will bear witness, precise witness!

May 27, 1942

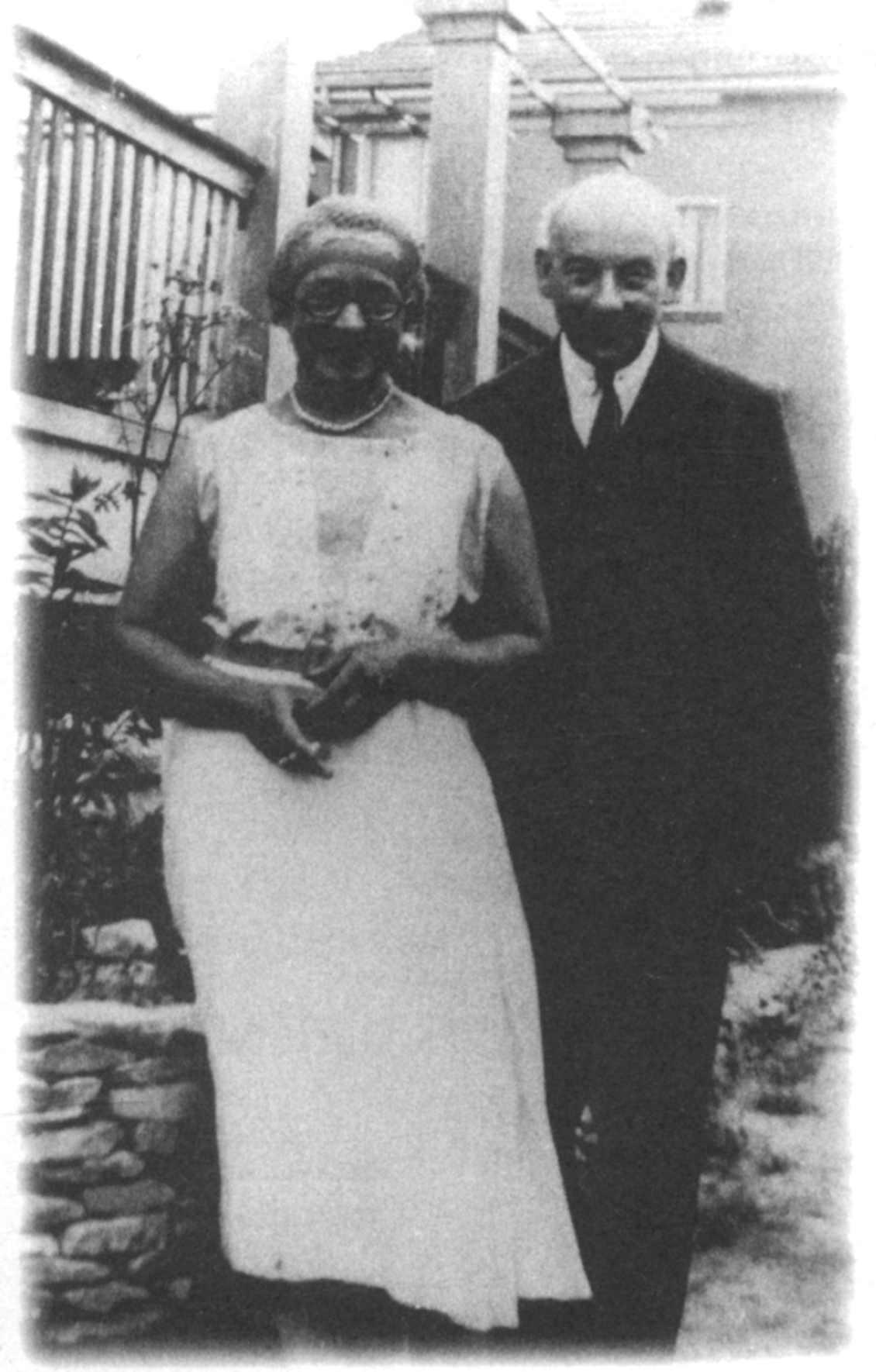

Eva and Victor Klemperer, c. 1940.

PREFACE

The Lives of Victor Klemperer

Escape

At the beginning of February 1945, there were 198 registered Jews, including Victor Klemperer, left in the city and the district of Dresden. The remainder of the 1,265 who had been in the city in late 1941 had been deported to Riga, to Auschwitz, to Theresienstadt.

All the remaining Jews in Dresden had non-Jewish wives or husbands. This had placed them in a relatively privileged position but dependent on the courage and tenacity of their marriage partners. If the Aryan spouse died or divorced them, they would immediately be placed on the deportation list. The majority of such couples and families had been ghettoized, together with the less privileged Jews, in a dwindling number of Jews houses.

On the morning of Tuesday, February 13, all Jews considered capable of physical labor were ordered to report for deportation early on Friday, February 16. The mixed marriages of Dresden were finally to be split up. Victor Klemperer regarded this as a death sentence for himself and the others. Then, on the evening of February 13 the catastrophe overtook Dresden: the bombs fell, the houses collapsed, the phosphorus flowed, the burning beams crashed onto the heads of Aryans and non-Aryans alike, and Jew and Christian met death in the same firestorm; whoever of the bearers of the star was spared by this night was delivered, for in the general chaos he could escape the Gestapo.

Victor Klemperer and the other Jews who survived the Allied raid and the subsequent firestorm had experienced a double miracle, had been doubly lucky.

In the confusion following the destruction of the city, Victor Klemperer pulled off the yellow Jews star, and he and his wife merged with the other inhabitants fleeing the city. It was easy enough for them to claim they had lost their papers. Nevertheless, afraid of being recognized and denounced, they went on the run across Germany for the next three months, until the village they had reached in southern Bavaria was occupied by American forces.

Contradictions

On the night of the Dresden firestorm, when Victor Klemperer escaped both the Allied bombs and the Gestapo, he was already sixty-three. He was born in 1881, the youngest child of Wilhelm Klemperer, rabbi in the little town of Landsberg on the Warthe (today the Polish town of Gorzow Wielkopolski), in the eastern part of the Prussian province of Brandenburg. Three brothers and four sisters survived into adulthood; the famous conductor Otto Klemperer was a cousin, but there was little contact between the two parts of the family. By the time Victor was nine, his father, after an unhappy interlude with the Orthodox congregation at Bromberg (today Bydgoszcz), had been appointed second preacher of the Berlin Reform Congregation. The whole family appears to have felt relieved at the change, and according to his autobiography, Victor immediately relished the freedom and excitement of the big city.

Observance at the Reform Synagogue was extremely liberal. The services themselves were conducted almost entirely in German, and on a Sunday, heads were not covered, and men and women sat together. There was no bar mitzvah; instead, at the age of fifteen or sixteen, boys and girls were confirmed together on Easter Sunday. There were neither Sabbath restrictions nor dietary proscriptions. The sermons seem, to some degree, to have expressed the ethical tradition of the German Enlightenment. In other words, services approximated Protestant practice, and Judaism here became as rational and progressive as it could be while retaining a Jewish identity. This was not the norm of Jewish congregations, but it is nevertheless exemplary of a tradition of merging with the dominant culture. The Reform Synagogue can perhaps be regarded as something of a halfway house to conversion to Protestantism, which had become common in Prussia since the early nineteenth century. (The parents of Karl Marx and Felix Mendelssohn were among only the most prominent examples; conversion, of course, remained for a long time a condition of state service.) Wilhelm Klemperer raised little objection when his own sons were baptized as Protestants. Indeed, Victor Klemperers three elder brothers seem to have gone out of their way to deny their Jewish origins. The biographical note prefacing the doctoral thesis of Georg Klemperer, the oldest brother, begins with the words, I was born the son of a country cleric.