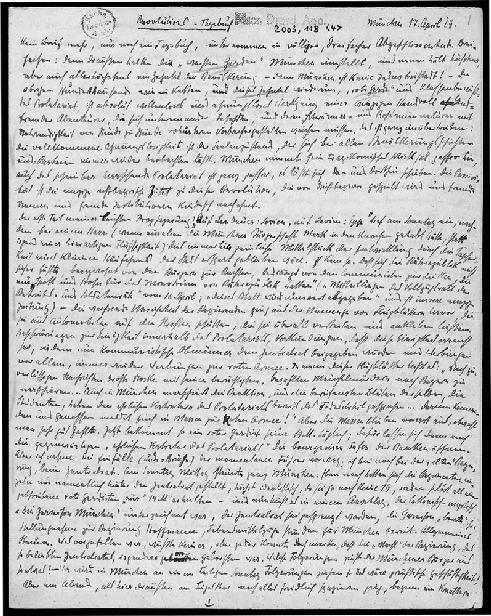

Appendix

The first page of the manuscript of Klemperers Revolutionary Diary from 1919.

The German Revolution of 191819

A historical essay

Wolfram Wette

Even 100 years later, the German revolution of 191819 attracts our interest. This should come as no surprise. It was the only revolution to have taken place in Germany to that point, and it was relatively successful. It produced the first German democracy, the Weimar Republic. The revolution of 191819 was a turning point in modern German history. It has a permanent place in Germanys memory of its democratic traditions. To understand the reasons for this revolution and the forms that it took, it is important to know that it was nothing less than a strategically planned coup by professional revolutionaries who were prepared to use violence. No, it was born from the protest of millions of Germans against the Great War, which had lasted for four years. The war had brought death and misery to the country, and most people longed for a swift end to it. From 1916 the country was ruled by a military dictatorship, namely, the Supreme Army Command (Oberste Heeresleitung, or OHL) under General Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg and his deputy, General Erich Ludendorff. The latter was the actual strongman in the OHL.

In the spring and summer of 1918, it became apparent that these generals were still making no effort to move toward a negotiated peace. A parliamentary majority had proposed this as a political goal one year earlier. Instead, those in power wanted to continue fighting and let the homeland continue suffering in order to achieve the military victorious peace that was supposedly still possible. This was the breeding ground for the protest movements that emerged in the course of 1918, both on the front line and back at home. In March, German soldiers on the Western front, on French soil, made their feelings about Germanys war policy known by engaging in a covert military strike that they concealed from the military leadership. Major strikes were held at home as well, even in armaments plants critical to the war effort. A massive anti-war movement formed and took to the streets demanding Peace, Freedom, Bread! peace meaning a rapid end to the war, freedom meaning replacing the militaristic authoritarian state with a democratic republic, and bread meaning the state should focus at long last on feeding its needy population, in part by endeavoring to lift the Allied blockade on food imports.

At the end of October and start of November 1918, sailors from the Imperial High Seas Fleet mutinied, first in Wilhelmshaven and then in Kiel, in the hopes of quickly ending the war. By fundamentally calling the old power structures into question while simultaneously allying themselves with the local workforce, the sailors gave the signal for the start of the German revolution. This spread like a tidal wave from the north to cover all of Germany. It arrived in Munich on November 7 and 8, 1918, even before it had reached the imperial capital of Berlin. As had previously happened in Kiel, revolutionary soldiers allied themselves with revolutionary workers in many other German cities. From their own ranks they appointed workers and soldiers councils on a local, regional, and national level, and these revolutionary ruling bodies took the place of the old powers.

A politically decisive breakthrough was achieved on November 9 in Berlin. The workers in Berlins large factories went on general strike. The soldiers in the garrison declared their solidarity with the strikers. Under pressure, Kaiser Wilhelm II abdicated. Reich Chancellor Prince Max von Baden relinquished his office to the chairman of the Majority Social Democratic Party of Germany (MSPD), Friedrich Ebert. Philipp Scheidemann, a long-serving parliamentarian and one of the best-known members of the MSPD, proclaimed from the balcony of the Reichstag building: Long live the German Republic! A few streets away, Reichstag delegate Karl Liebknecht from the Independent Social Democratic Party of Germany (USPD) proclaimed the Free Socialist Republic of Germany.

Then came the revolution from below. Under pressure from the rank and file, who were pushing for the two social democratic parties to join forces, a new government was brought into being on November 10, 1918, a revolutionary body calling itself the Council of Peoples Deputies. It was made up of three experienced politicians each from the two social democratic parties. Ebert assumed chairmanship of it. This revolutionary government issued an important proclamation on November 12, 1918, An das deutsche Volk! (To the German People!), in which it announced the enforcement of political reforms: the introduction of an eight-hour workday as well as general, equal, secret, and direct voting rights for everyone from the age of 20 (including women), and the election of a constituent National Assembly. The issue of socialization that is, the communization of the means of production was not addressed in the proclamation. This was due to the two parties differing ideas about the goals of the revolution, and it would be a source of conflict in the following months. The revolutionary upheaval in the Reich capital of Berlin, which would affect the entire German Reich, was largely calm and bloodless contrary to some expectations. The old system collapsed without a fight. Some historians believe the peaceful course of the November Revolution can be attributed to the fact that the old powers resigned without resistance. Others point out the countrys advanced state of democratization and high degree of industrialization and, as a result of these two factors, the German populations widespread anti-chaos instinct, which included a desire for administrative continuity.

On November 11, 1918, the guns finally fell silent, just as the mass movement had been demanding for months. But the leading generals Hindenburg and Ludendorff evaded having to sign the armistice and thus accept responsibility for the military defeat of the German Reich. Instead, the government of Peoples Deputies sent Center Party politician Matthias Erzberger to the French city of Compigne to sign the armistice agreement. In the period that followed, the responsible officers led millions of German soldiers from the front lines back to Germany, where they were demobilized. Spontaneous demobilizations occurred wherever the military bureaucracy was unable to issue proper discharge papers. Everyone was happy to have survived the war, and they all desperately wanted to be back home before Christmas.

While the revolutionary upheaval was under way in Berlin, German NCO Victor Klemperer was in the Lithuanian city of Vilnius, which was occupied by German troops. In 1915, the 34-year-old (born October 9, 1881) who was married and had both a doctorate and a university lecturers qualification in Romance philology had reported as a war volunteer as proof of his patriotism. Klemperer, the son of a Jewish father and Jewish mother, also demonstrated his eagerness to assimilate by converting to Protestantism. From November 1915 to March 1916 he was deployed on the Western front, in Flanders. In the autumn of 1918 he was performing relatively safe military duties in Vilnius, in the press office of the staff of Ober Ost, as the office of the supreme commander of the entire German armed forces in the East was known.

After the armistice agreement of Compigne, Klemperer swiftly found a way to get back to the West entirely legally by train. He first stopped over for several weeks in Leipzig, where his wife, Eva, lived, and then traveled on in mid-December 1918 to spend a few days in Munich, where his reserve unit, the Prince Luitpold 7th Field Artillery Regiment, was stationed. Sergeant Klemperer placed great value in bringing his military service to a formally proper end. His former regimental comrades honored this by not only issuing him the necessary discharge papers without complaint, but also furnishing him with wages, leave and ration cards.