Contents

Guide

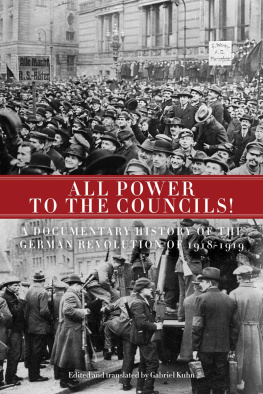

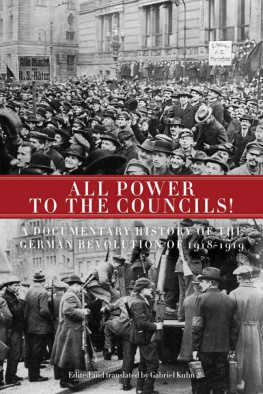

A Peoples History of the German Revolution

Peoples History

History tends to be viewed from the perspective of the rich and powerful, where the actions of small numbers are seen to dictate the course of world affairs. But this perspective conceals the role of ordinary women and men, as individuals or as parts of collective organisations, in shaping the course of history. The Peoples History series puts ordinary people and mass movements centre stage and looks at the great moments of the past from the bottom up.

The Peoples History series was founded and edited by

William A. Pelz (19512017).

Also available:

Long Road to Harpers Ferry

The Rise of the First American Left

Mark A. Lause

A Peoples History of the Portuguese Revolution

Raquel Varela

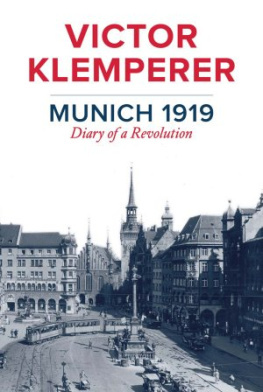

A Peoples History of

the German Revolution

191819

William A. Pelz

Foreword by Mario Kessler

First published 2018 by Pluto Press

345 Archway Road, London N6 5AA

www.plutobooks.com

Copyright the Estate of William A. Pelz 2018

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 978 0 7453 3711 1 Hardback

ISBN 978 0 7453 3710 4 Paperback

ISBN 978 1 7868 0248 4 PDF eBook

ISBN 978 1 7868 0250 7 Kindle eBook

ISBN 978 1 7868 0249 1 EPUB eBook

This book is printed on paper suitable for recycling and made from fully managed and sustained forest sources. Logging, pulping and manufacturing processes are expected to conform to the environmental standards of the country of origin.

Typeset by Stanford DTP Services, Northampton, England

Simultaneously printed in the United Kingdom and United States of America

Contents

Foreword

Mario Kessler

A Peoples History of the German Revolution, 191819, is the last book by the American historian William Arthur (Bill) Pelz, who died at age 66 on December 10, 2017 in his hometown of Chicago.

The son of a bus driver, Bill Pelz was connected to working people by origin and attitude. He wrote his doctoral thesis in 1988, inspired by Arthur Rosenbergs classic work The Birth of the German Republic, on the Spartacus League in the German November Revolution. Documentary books on Eugene V. Debs and Wilhelm Liebknecht followed. Against Capitalism: The European Left on the March was published in 2008, Karl Marx: A World to Win four years later, German Social Democracy: A Documentary History in 2015, and finally A Peoples History of Modern Europe in 2016. Among his numerous editorial works, his contributions to the Encyclopedia of the European Left and his appointment as a co-editor of Rosa Luxemburgs works in English must also be mentioned. A lifelong Chicagoan, he held positions as a contingent professor at Roosevelt University, and then as Director of Social Science Programs at De Paul University. For the past 20 years, the Marxist historian was professor of European history and political science at Elgin Community College on the outskirts of Chicago.

A Peoples History of the German Revolution, 191819, a manuscript completed by Pelz just days before his unexpected loss, returns the author to the starting point of his career as a historian. The title should remind us of Howard Zinns A Peoples History of the United States. Both Zinns and Pelzs works unashamedly make the social history of working-class women and men accessible, vital and popular. Yet, unlike Zinns documentary approach, Pelzs interpretive history of the German Revolution might benefit from an introduction to the historical context of this crucial moment in German and working-class history for those less familiar with German history. Why should readers be curious about this book, a brilliant and entirely fresh overview of an important period of German and European history?

The book introduces the reader to German social history of the nineteenth and early-twentieth centuries; a time that seems distant, but whose problems, as this book shows, remain present today. Compared to England and France, Germany was a belated nation: its bourgeoisie only appeared as a historical force when it felt the breath of the emerging working class at its neck. Thus, in the European revolutionary year of 1848, the middle class was neither willing nor able to fight out the struggle for national unity together with lower classes, especially workers. Instead, the German bourgeoisie allied itself with the forces led by Prussian Chancellor Otto von Bismarck. After the Prussians fought and won three wars against their neighbors, they unified the new state from above; in 1871, most German-speaking territories became part of a new German Empire (with the notable exception of Austria which remained part of the Habsburg Empire). This sealed the alliance between the emerging imperialist bourgeoisie and the old nobility, the class which provided the German military and diplomatic elite.

Denied any meaningful political role in the new state, workers were attracted to the Social Democratic Party (SPD), whose path to the strongest electoral force in the German Empire is impressively traced in this book. The social-democratic workers and the left-wing intellectuals supporting them formed an increasingly dense network of trade unions, media, cooperatives and cultural organizations whose structures grew as an alternative to the dominant culture of bourgeois German society.

But this social-democratic counter-society faced a dilemma: the more it grew into a counter-society in the state, the more its leaders and administrative functionaries no longer wanted to eliminate this state. Rather than abolish bourgeois society in the Hegelian sense, SPD leaders and theorists sought to peacefully take over the states institutions through social and electoral reform. At the same time, revolutionary rhetoric remained central to SPD theory.

As early as 1896, Bertrand Russell sharply recognized that this contradiction within the SPD overlapped the fundamental contradiction of German societythat the largest and strongest class remained excluded from participation in society. Although men, but not women, had universal, equal and secret suffrage in the Reich, the German parliament, the Reichstag, had no real executive power in comparison with the Emperor. In Prussia, by far the most important of the German states, a three-class franchise system gave the dispossessed classes less voting rights than the upper class. Moreover, the SPDs increasing bureaucratic direction resulted in a distinct cultural cleavage between the partys career-oriented professionalism and its working-class electoral and trade union base.

Social Democratic Party leaders believed that through an alliance with the liberal wing of the bourgeoisie they would gain one concession after another from the ruling classes, resulting in the conditions for a peaceful transition to socialism. A minority in the party criticized these policies as reformist illusions, Rosa Luxemburg perhaps most notably. The Polish Marxist, who devoted her life to the German workers movement, came to understand most precisely that the liberal bourgeoisie would rather seek a compromise with the reactionary landlords, industrialists, and the military at the expense of the working class, and that the ruling elites would never give away class power to workers in the form of civil and economic rights. In fact, the Imperial Court, the landlords and the military forged an ever stronger alliance with the industrial and financial capital in order to realize their great political project, that Germany would be elevated from the rank of a European power to the rank of the pre-eminent European power, and a world power, even if it required deadly war with neighboring states.