Preface

The enemys revengeful hysteria

The German delegation reacted to the peace proposals presented at Versailles on 7 May 1919 with a combination of disbelief and outrage. A copy of the bulky draft treaty before him, the delegations leader, Foreign Minister Count Ulrich von Brockdorff-Rantzau, told the worlds peacemakers gathered in the Trianon Palace, We are aware that the strength of German arms has been crushed. We can feel all the power of hate we must encounter in this assembly It is demanded of us that we admit ourselves the only parties guilty of this war on my lips such an admission would be a lie.

Georges Clemenceau, the French prime minister and chairman of the Peace Conference, had left the Germans in no doubt about the victors attitude in his brusque opening speech. This is neither the time nor the place for superfluous words. You have before you the accredited plenipotentiaries of the greater and lesser Powers, both Allied and Associated, that for four years have carried on without respite the merciless war which has been imposed upon them. The time has come for a heavy reckoning of accounts. You have asked for peace. We are prepared to offer you peace. There would be no face-to-face negotiations, though the Allies and Associated powers (hereafter, the Allies) would accept written comments on the draft. Germany was given two weeks to digest and comment on the treatys 440 articles, some 80,000 words covering over 200 pages.

By the terms of the treaty, Germany was to lose almost a tenth of her population, 25,000 square miles of territory in Europe to her neighbours, and her African and Asian colonies. To ensure that Germany would not emerge from the war larger than she had entered it in 1914, union with what remained of the diminished Austrian Empire was forbidden. The army was to be limited to 100,000 men, conscription would be abolished, no air force permitted and the navy severely restricted. Germany would pay reparations for the damage she and her allies had caused in the war, the precise amount to be determined by May 1921. Articles 227231 caused the greatest uproar in Germany. The former Kaiser and military advisors accused of war crimes were to be handed over to the Allies for trial and Germany was to acknowledge her responsibility for the war.

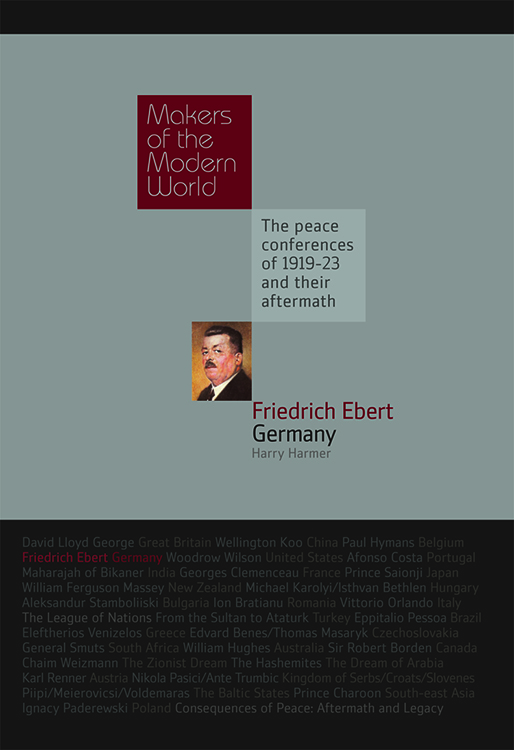

After a hurried translation and scrutiny of the draft treaty, Brockdorff-Rantzau complained to Clemenceau on 9 May that some demands were intolerable, while others were impossible to comply with. On the same day Germanys provisional Reich President, Friedrich Ebert, accused the Allies of abandoning their promise that President Woodrow Wilsons Fourteen Points would form the basis of what Germany had believed would be a just settlement. From such an imposed peace fresh hatred would be bound to arise between the nations, and in the course of history there would be new wars The dismemberment and mangling of the German Nation, the delivering of German labour to foreign capitalism for the indignity of wage slavery, and the permanent fettering of the young German republic by the Ententes imperialism is the aim of this peace of violence In view of this danger of destruction, the German nation and the Government which it chose must stand by each other, knowing no parties. The entire sweep of the German press liberal, socialist, conservative and nationalist echoed his sentiments. Cardinal Hartmann, the Archbishop of Cologne, appealed to the Pope to intervene and prevent what he described as a cruel imposition that would utterly ruin Germany.

What hand would not wither that binds itself and us in these fetters?

SCHEIDEMANN, 12 MAY 1919

The German Chancellor Philipp Scheidemann condemned the treaty in the National Assembly in Berlin on 12 May. Pointing to the document before him he said, I ask you: who can, as an honest man, I will not say as a German, but only as an honest, straightforward man, accept such terms? What hand would not wither that binds itself and us in these fetters? Speakers for each of the parties rose to echo Scheidemann. The Social Democrat Heinrich Mller described the treaty as intolerable and said it could not, in any case, be fulfilled. Only Hugo Haase, leader of the Independent Socialists who had broken from the Social Democrats, argued that Germany should sign on the basis that the treaty would be made irrelevant by the revolution he believed was sweeping the world.

Addressing a large demonstration at the Lustgarten in Berlin, Ebert said Germany could not accept the treaty as it stood, the product of the enemys revengeful hysteria.

Brockdorff-Rantzau despatched Germanys voluminous, detailed, but ultimately fruitless counterproposals to Clemenceau on 29 May. In their reply on 16 June, the Allies left the thrust of the treaty unchanged, granting only minor concessions on Germanys borders with the new Polish state. Germany was given five days to accept or reject the terms, with the clear implication that rejection meant a renewal of the war. The German delegation arrived at Weimar, where the government was now sitting, on 18 June. Brockdorff-Rantzau advised the cabinet that the delegation considered the treaty unacceptable. Discussion among the ministers, chaired by President Ebert, continued until 3 oclock the following morning. The cabinet had also to consider advice from the army commander, Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg. What he said was carefully ambiguous: the army would be unable to resist a renewed advance by the overwhelming might of the British, French and American armies. A favourable outcome of our operations is therefore very doubtful, but as a soldier I would rather perish in honour than sign a humiliating peace. The cabinet divided, six in favour of signing, eight including Chancellor Scheidemann against. Ebert said that without a cabinet consensus, the National Assembly would have to make the final decision.

The divisions in the cabinet reflected uncertainties in the parties that made up the coalition. In separate meetings on 20 June the Democrats voted unanimously against signing, the Social Democrats 75 for and 35 against, while a majority of the Centre Party favoured acceptance provided the Allies removed the articles on war guilt and war crimes. Scheidemann went directly from the Social Democrats meeting to Eberts office, accompanied by Otto Landsberg, Minister of Justice and a member of the deputation at Versailles. Both told him they were resigning. Ebert asked them to stay. When they refused, a despairing Ebert who in May had publicly proclaimed Germanys determination to reject the treaty said he must also give up his office. They persuaded him to remain, arguing that his resignation would leave Germany in chaos. A little later Brockdorff-Rantzau announced that the Versailles delegation would be standing down.

Three days before the Allied ultimatum for signature was due to expire Germany had no government and no delegation to the Peace Conference. On 22 June, with one day remaining, the Social Democrat Gustav Bauer formed a new coalition with the Centre. His administrations first task, Bauer said, would be to conclude what he called this peace of injustice. Later that day he presented a resolution to the National Assembly: The government of the German republic is ready to sign the peace treaty without thereby acknowledging that the German people are the responsible authors of the war and without accepting Articles 227 to 231. After three hours of debate the deputies voted 237 to 138 in favour of the resolution.