Table of Contents

Introduction

A successful workers revolution in Germany in 1923 would have changed the entire course of the centurys history. A second workers statein one of the most advanced industrial countrieswould have made nonsense of Stalins slogan of socialism in one country and enormously enhanced the chances of spreading the revolution to France, Britain and Italy. And Adolf Hitler, even if he had escaped summary execution, would have found it hard to make any impact on events. The two great tyrannies of the century, Stalins Russia and Hitlers Germanywith their host of imitators and would-be imitatorswould have been aborted. Of course, there would have been other dangers, other possibilities of defeat still to face. But the scales would have been shifted significantly in favor of socialism.

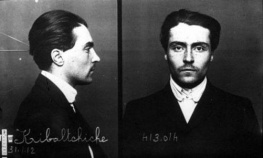

One person who had the opportunity to observe and analyze the events of 1923 at first hand was Victor Serge. Serge was still a young man32in 1923, but he had an extensive revolutionary past behind him. Born in Brussels to Russian revolutionary parents in exile, he went to Paris while still in his teens and became active in anarchist journalism. He spent the years 1913 to 1917 in jail after defending the anarchist bank robbers of the notorious Bonnot Gang. He went next to Spain, where he participated in the unsuccessful 1917 Barcelona syndicalist uprising. Then he made his way to revolutionary Russia, where he soon decided to become a member of the Communist Party (though he never abandoned political dialogue with his former anarchist comrades). His experiences in revolutionary Russia are described in his Memoirs of a Revolutionary ,

By 1922 Serge was feeling considerable disillusion at the way events were developing in Russia. He believed that only by spreading could the revolution survive: Relief and salvation must come from the west. From now on it was necessary to work to build a Western working-class movement capable of supporting the Russians and, one day, superseding them. With Zinovievs assistance he got a job in Berlin with the Comintern [Communist International] press agency Inprekorr ( Correspondance internationale ), which provided reports for the Communist press around the world. He spent most of 1922 and 1923 in Berlin, then worked in Vienna and elsewhere before returning to Russia in 1926. He became a supporter of the Left Opposition, and was sent into internal exile before being expelled from the USSR. Back in the West he continued to be an intransigent anti-Stalinist writer, who also produced a series of outstanding novels. With the German occupation of France, he left Europe for Mexico, where he died in 1947.

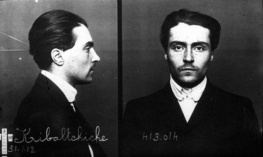

In his Memoirs Serge gives only a relatively sketchy account of his activities in Germany. Even before the major clampdown of November 1923 his activity was at best semi-legal. Many articles under his name appeared in the Comintern press of the time, but they generally dealt with Russian affairs. It was doubtless useful to let the German authorities think Victor Serge (itself a pseudonym; he was born Kibalchich) was in Russia. But for German matters, on which Serge wrote a weekly column between July and December 1923, he adopted the pseudonym R. Albert. As a result, Serges writings on the German revolution lay for many years ignored and forgotten in the files of Comintern publications.

Albert was first identified as Serge by Richard Greeman after a study of the style and content of more than 20 articles in Correspon-dance internationale and the Bulletin communiste . The selection in this book is inspired by Brous edition, but I have added eight additional pieces not included by Brou (see the appendix for details of the comparison between the two books). In fact, on close study Serges authorship becomes obvious. His style, his eye for significant detail, are unmistakable. Even his characteristic punctuationthe way in which he frequently, and often irritatingly, ends a sentence with three dotsis there. Doubtless the German police did not employ experts in literary analysis.

Much that has been written on Germany in 1923 has focused on the relations between the German Communist Party (KPD) and the Russian leadership of the Comintern. Serge tells us nothing new on thiseven if he had been aware of such discussions, they would not have been suitable matter for publication. What he does give is a vivid account of events in Germany during 1923, and in particular a picture of the consciousness and mood of the working class, the crucial factor in evaluating any revolutionary situation. Serge is describing the German events for an audience abroadand especially for the French lefthis former comrades and the people whose solidarity would be crucial if German workers made a bid for power.

Working in a press agency, Serge read the entire range of the German press from far left to far right. He also had access to the KPDs internal channels of communication. But on top of that he found time to walk the streets and observe daily life. He documented the inflation of 1923 with lists of figures that sometimes become wearisome. But he always quickly returned to the concretewhat did it mean for a worker with two children who wanted to buy some bread and an egg? The major events of the yearthe French occupation of the Ruhr, the rise of Hitler, the creation of workers governmentswere followed through week by week.

But, despite their fragmentary appearance, Serges reports were not just random impressions. Serges account was in fact structured by a rigorously Marxist, materialist method. At the very core was the theme to which he returned again and againthe need for German capitalism to restore its profits. There was only one way it could achieve thisby increasing the level of exploitation. Hence the key aims of cutting real wages and extending the working day from eight to ten hours (reversing the one real gain of the 1918 revolution). It is this that makes sense of the otherwise confusing political fluctuations of the period. Would the bourgeoisie opt for parliamentary democracy (with or without the social democrats), for military dictatorship, or for the Nazis? The answer: whichever would best enable it to increase exploitation and raise profits.

Around this central core Serge accumulated a mass of detail which illuminated the crisis. A trial verdict made clear the balance of class forces. An art exhibition revealed the way in which capitalist decline dehumanized. (It is hard to know which is more surprising: that art exhibitions still took place in 1923, or that Serge found time to attend them.) When he observed a policeman watching a bread queue and looking miserable, he speculated that the cause of the misery was the fact that his wife was in the queue. In one sentence Serge said more about the contradictory nature of the bourgeois state than many learned tomes.

For many years Serges reputation has rested on his novels and his Memoirs . But his earlier writings from his period as a Bolshevik activist show that before being a remarkable novelist he was a remarkable journalist. At a time when we have seen so many journalists, during the recent Balkan War, acting as mere transmitters of the government line, it is important to remember that revolutionary journalism has a quite different historythat it can combine passionate commitment with honest observation. Serge wrote with wit, humor and irony, but above all it was anger that motivated his writinganger at a system in which the rich got richer while, over ten years, working people faced first slaughter in the trenches, then armed repression, and finally starvation. It is Serges anger, controlled but never suppressed, which makes this book such a striking testimony to the experience of a revolutionary year.