Praise for Birth of Our Power

Nothing in it has dated. It is less an autobiography than a sustained, incandescent lyric (half-pantheist, half-surrealist) of rebellion and battle.

Times Literary Supplement

Surely one of the most moving accounts of revolutionary experience ever written.

Neal Ascherson, New York Review of Books

Probably the most remarkable of his novels. Of all the European writers who have taken revolution as their theme, Serge is second only to Conrad. Here is a writer with a magnificent eye for the panoramic sweep of historical events and an unsparingly precise moral insight.

Francis King, Sunday Telegraph

Intense, vivid, glowing with energy and power A wonderful picture of revolution and revolutionaries. The power of the novel is in its portrayal of the men who are involved.

Manchester Evening News

Birth of Our Power is one of the finest romances of revolution ever written, and confirms Serge as an outstanding chronicler of his turbulent era. As an epic, Birth of Our Power has lost none of its strength.

Lawrence M. Bensky, New York Times

Editor: Sasha Lilley

Spectre is a series of penetrating and indispensable works of, and about, radical political economy. Spectre lays bare the dark underbelly of politics and economics, publishing outstanding and contrarian perspectives on the maelstrom of capitaland emancipatory alternativesin crisis. The companion Spectre Classics imprint unearths essential works of radical history, political economy, theory and practice, to illuminate the present with brilliant, yet unjustly neglected, ideas from the past.

Spectre

Greg Albo, Sam Gindin, and Leo Panitch, In and Out of Crisis: The Global Financial Meltdown and Left Alternatives

David McNally, Global Slump: The Economics and Politics of Crisis and Resistance

Sasha Lilley, Capital and Its Discontents: Conversations with Radical Thinkers in a Time of Tumult

Sasha Lilley, David McNally, Eddie Yuen, and James Davis, Catastrophism: The Apocalyptic Politics of Collapse and Rebirth

Peter Linebaugh, Stop, Thief! The Commons, Enclosures, and Resistance

Spectre Classics

E.P. Thompson, William Morris: Romantic to Revolutionary

Victor Serge, Men in Prison

Victor Serge, Birth of Our Power

Birth of Our Power

Victor Serge. Translated by Richard Greeman

Copyright Victor Serge Foundation

Translation, introduction, and postface 2014 Richard Greeman

This edition 2014 PM Press

First published as Naissance de notre force. Paris: Les Editions Rieder, 1931.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be transmitted by any means without permission in writing from the publisher.

ISBN: 978-1-62963-030-4

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014908064

Cover by John Yates/Stealworks

Interior design by briandesign

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

PM Press

PO Box 23912

Oakland, CA 94623

www.pmpress.org

Printed in the USA by the Employee Owners of Thomson-Shore in Dexter, Michigan. www.thomsonshore.com

Contents

Introduction

by Richard Greeman

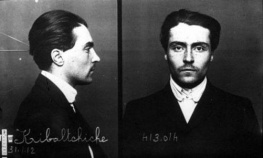

Birth of Our Power is an epic novel set in Spain, France, and Russia during the heady revolutionary years 19171919. It was composed a decade later in Leningrad by a remarkable witness-participant, the Franco-Russian writer and revolutionary Victor Serge (18901947). Serges tale begins in the spring of 1917, in the third year of insane mass slaughter in the blood- and rain-soaked trenches of World War I, when the flames of revolution suddenly erupt in Russia and Spain. Europe is burning at both ends. In February, the Russian people overthrow the Czar, while in neutral Spain militant anarcho-syndicalist workers allied with middle-class Catalan nationalists rise up in mass strikes aimed at taking power. Although the Spanish uprising eventually fizzles, in Russia the workers, peasants, and common soldiers are able to take power and hold it. Birth of Our Power chronicles that double movement.

Serges novel follows an anonymous narrators odyssey from Barcelona to Petrograd, from one red city to the other, from the romanticism of radicalized workers awakening to their own power in a sun-drenched Spanish metropolis to the grim reality of workers clinging to power in Russias dark, frozen revolutionary outpost. Where Dickens constructed his Tale of Two Cities around the opposition between conservative London (white) and revolutionary Paris (red) Serges novel is based on the opposition of two cites, both red: Barcelona, the city we could not take, and Petrogradthe starving capital of the Russian Revolution, besieged by counterrevolutionary whites.

Like Homers Odysseus and Virgils Aeneas, Serges nameless narrator is fated to pass through the Underworld on his two-year odyssey from the defeated revolution to the victorious one. He spends over a year in French World War I concentration camps for subversives. The novel ends in Petrograd with something of an anti-climax: The city of victorious revolution, the city where we have taken power, is revealed not as a vast tumultuous forum, but as a grim, half-empty metropolis, not at all dead, but savagely turned in on itself, in the terrible cold, the silence, the hate, the will to live, the will to conquer.

Whereas the defeat in Barcelona is partially transformed into a victory by the heroic exaltation of the masses newly awakened to a sense of their own power, in Petrograd, the original question of Can we take power? is superseded by an even more difficult one: Can we survive and learn to use that power? The novel thus plays on the ironic themes of victory-in-defeat (Barcelona) and defeat-in-victory (Petrograd).

Autobiography into Fiction

Serge lived it all. The novel follows its authors own two-year itinerary across war-torn Europe from an aborted revolt in Spain to the promise of a victorious revolution in Russia, but strange to say, the novel is not really autobiographical. Serges anonymous narrator is little more than a camera eye giving multiple perspectives on the action. He has no personal life. He never gets to speak a line, only to observe and narrate. Indeed, the pronoun I appears only once or twice per chapter. The fraternal we, the first-person plural, is Serges preferred part of speech, beginning with the very first sentence, indeed with the title.

I feel an aversion to using I as a vain affirmation of the self, containing a good dose of illusion and another of vanity or arrogance. Whenever possible, that is to say whenever I am not feeling isolated, when my experience highlights in some way or other that of people with whom I feel linked, I prefer to employ the pronoun we, which is truer and more general. We never live only by our own efforts, we never live only for ourselves; our most intimate, our most personal thinking is connected by a thousand links with that of the world.

Serges novel presents these events in a kaleidoscoping series of tableaux studded with epiphaniesrealistic incidents that unveil transcendent social truths. Given Birth of Our Powers somewhat disjointed, cinematographic styleno doubt influenced by such modernist masterpieces as Andrei Bielys

Next page