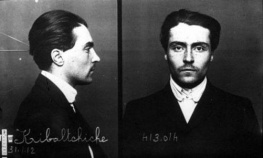

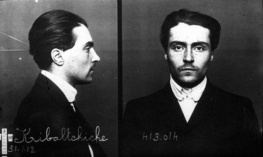

VICTOR SERGE (18901947) was born Victor Kibalchich in Brussels in 1890, the son of Russian political exiles. As a young man, he lived in Paris, moving in anarchist circles and enduring five years in prison for his beliefs. In 1919, he went to Russia to support the Bolshevik Revolution. Traveling between Petrograd, Moscow, Berlin, and Vienna, Serge served as the editor of the journal Communist International, but in 1928 his condemnation of Stalins growing power led to his expulsion from the Communist Party and imprisonment. Released, Serge turned to writing fiction and history, only to be arrested again in 1933 and deported to Central Asia. International protests from eminent figures such as Andr Gide succeeded in securing Serges freedom, and in 1936 he left Russia for exile in France. There Serge continued to write fiction, while struggling to expose the totalitarian character of the Soviet state; for a while he also aided Trotsky, translating a number of his works. After the German occupation of France, Serge fled to Mexico, where he died in 1947. Along with his most famous work, The Case of Comrade Tulayev, Serges many books include Year One of the Russian Revolution, Memoirs of a Revolutionary, From Lenin to Stalin, and the novels Conquered City, Midnight in the Century, Birth of Our Power, Men in Prison, and The Long Dusk.

SUSAN SONTAG is the author of four novels, The Benefactor, Death Kit, The Volcano Lover, and In America, which won the 2000 National Book Award for Fiction; a collection of stories, I, Etcetera; several plays, including Alice in Bed and Lady from the Sea; and seven works of nonfiction, among them Where the Stress Falls and Regarding the Pain of Others. Her books have been translated into thirty-two languages. In 2001, she was awarded the Jerusalem Prize for the body of her work; in 2003, she received the Prince of Asturias Prize for Literature and the Peace Prize of the German Book Trade.

THE CASE OF COMRADE TULAYEV

VICTOR SERGE

Translated from the French by

WILLARD R. TRASK

Introduction by

SUSAN SONTAG

NEW YORK REVIEW BOOKS

New York

CONTENTS

Unextinguished

(The Case for Victor Serge)

after all, there is such a thing as truth.

THE CASE OF COMRADE TULAYEV

How to explain the obscurity of one of the most compelling of twentieth-century ethical and literary heroes, Victor Serge? How to account for the neglect of The Case of Comrade Tulayev, a wonderful novel that has gone on being rediscovered and reforgotten ever since its publication, a year after Serges death in 1947?

Is it because no country can fully claim him? A political exile since my birth so Serge (real name: Victor Lvovich Kibalchich) described himself. His parents were opponents of tsarist tyranny who had fled Russia in the early 1880s, and Serge was born in 1890 in Brussels, as it happened, in mid-journey across the world, he relates in his Memoirs of a Revolutionary, written in 1942 and 1943 in Mexico City, where, a penurious refugee from Hitlers Europe and Stalins assassins at large, he spent his last years. Before Mexico, Serge had lived, written, conspired, and propagandized in six countries: Belgium, in his early youth and again in 1936; France, repeatedly; Spain, in 1917 it was then that he adopted the pen name of Serge; Russia, the homeland he saw for the first time in early 1919, at the age of twenty-eight, when he arrived to join the Bolshevik Revolution; and Germany and Austria in the mid-1920s, on Comintern business. In each country his residence was provisional, full of hardship and contention, threatened. In several, it ended with Serge booted out, banished, obliged to move on.

Is it because he was not the familiar model a writer engaged intermittently in political partisanship and struggle, like Silone and Camus and Koestler and Orwell, but a lifelong activist and agitator? In Belgium, he militated in the Young Socialist movement, a branch of the Second International. In France, he became an anarchist (the so-called individualist kind), and for articles in the anarchist weekly he co-edited that expressed a modicum of sympathy for the notorious Bonnot gang after the bandits arrest (there was never any question of Serges complicity) and his refusal, after his arrest, to turn informer, was sentenced to five years of solitary confinement. In Barcelona following his release from prison, he quickly became disillusioned with the Spanish anarcho-syndicalists for their reluctance to attempt to seize power. Back in France, in late 1917 he was incarcerated for fifteen months, this time as (the words of the arrest order) an undesirable, a defeatist, and a Bolshevik sympathizer. In Russia, he joined the Communist Party, fought in the siege of Petrograd during the Civil War, was commissioned to examine the archives of the tsarist secret police (and wrote a treatise on state oppression), headed the administrative staff of the Executive Committee of the Third Communist International and participated in its first three congresses, and, distressed by the mounting barbarity of governance in the newly consolidated Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, arranged to be sent abroad by the Comintern in 1922 as a propagandist and organizer. (In this time there were more than a few freelance, foreign members of the Comintern, which was, in effect, the Foreign, or World Revolution, Department of the Russian Communist Party.) After the failure of revolution in Berlin and subsequent time spent in Vienna, Serge returned in 1926 to the USSR now ruled by Stalin and officially joined the Left Opposition, Trotskys coalition, with which he had been allied since 1923: he was expelled from the Party in late 1927 and arrested soon after. All in all, Serge was to endure more than ten years of captivity for his serial revolutionary commitments. There is a problem for writers who exercise another, more strenuous profession full-time.

Is it because despite all these distractions he wrote so much? Hyperproductivity is not as well regarded as it used to be, and Serge was unusually productive. His published writings almost all of which are out of print include seven novels, two volumes of poetry, a collection of short stories, a late diary, his memoirs, some thirty political and historical books and pamphlets, three political biographies, and hundreds of articles and essays. And there was more: a memoir of the anarchist movement in pre-First World War France, a novel about the Russian Revolution, a short book of poems, and a historical chronicle of Year II of the Revolution, all confiscated when Serge was finally allowed to leave the USSR in 1936, as the consequence of his having applied to Glavlit, the literary censor, for an exit permit for his manuscripts these have never been recovered as well as a great deal of safely archived but still unpublished material. If anything, his being prolific has probably counted against him.

Is it because most of what he wrote does not belong to literature? Serge began writing fiction his first novel, Men in Prison when he was thirty-nine. Behind him lay more than twenty years worth of works of expert historical assessment and political analysis, and a profusion of brilliant political and cultural journalism. He is commonly remembered, if at all, as a valiant dissident Communist, a clear-eyed, assiduous opponent of Stalins counterrevolution. (Serge was the first to call the USSR a totalitarian state, in a letter he wrote to friends in Paris on the eve of his arrest in Leningrad in February 1933.) No twentieth-century novelist had anything like his firsthand experiences of insurgency, of intimate contact with epochal leaders, of dialogue with founding political intellectuals. He had known Lenin Serges wife Liubov Rusakova was Lenins stenographer in 1921; Serge had translated

Next page