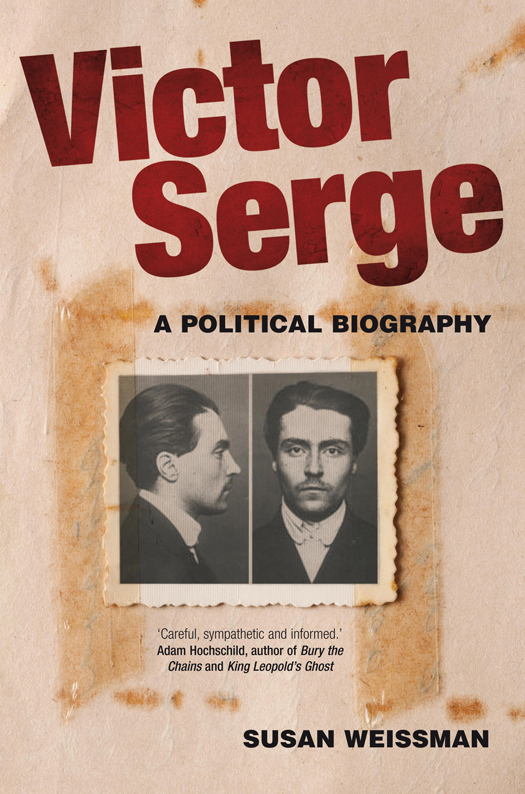

SUSAN WEISSMAN is a Professor of Politics at Saint Marys College in Moraga, California. She is an award-winning broadcast journalist, sits on the editorial boards of Critique and Against the Current, and is the editor of Victor Serge: Russia Twenty Years After and The Ideas of Victor Serge.

This updated paperback edition first published by Verso 2013

First published by Verso 2001

Susan Weissman 2001, 2013

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-84467-887-7

eBook ISBN: 978-1-78168-050-6

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

www.therunninghead.com

v3.1

To the memory of Roberto Naduris

whose bright smile is on every

page of this book,

to Eli and Natalia,

and to the memory of my parents,

Perle and Maurice Weissman

Contents

List of illustrations

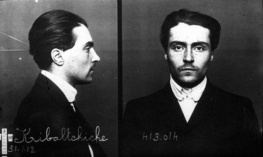

Victor Serge in the early 1920s

Serge, Vlady and Liuba following his release from prison, 1928

Anita Russakova, Serges sister-in-law

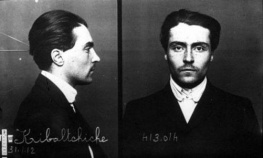

Serges uncle Nikolai Kibalchich, executed for his role in the assassination of Tsar Alexander II

The house at 33 Cavalry Street, Orenburg, where Serge and Vlady spent three years in exile. Painting by Vlady

Vladys sketch of Serge in Orenburg, signed V.V. Serge, Orenburg, 20 March 1936. Vlady was sixteen at the time

Serges NKVD file from Orenburg

Boris Mikhailovich Eltsin, leading Left Oppositionist and former chairman of the Soviet in Ekaterinburg, who was in Orenburg with Serge. Painting by Vlady

Vladys sketch of a memorial to Stalins victims

Receipt from the Department of Censorship, dated 29 October 1934 for Les Hommes perdus, Serges confiscated novel about pre-war France

Serge and Vlady, about 1936

Liuba, Jeannine, Serge and Vlady, Brussels, 1936 [Jeannine Kibalchich]

Liuba with Jeannine, France [Jeannine Kibalchich]

Safe conduct for Victor Serge and his party, issued by the French government, 1940. Note that Serges nationality is given as indeterminate

Laurette Sjourn [Jeannine Kibalchich]

Sketches of Serge in Marseilles, 1940, by Vlady

Charles Wolff, Victor Serge, Benjamin Pret and Andr Breton, standing in front of Villa Air-Bel, spring 1941 [Chambon Foundation]

Varian Fry standing in the pond at the Villa Air-Bel, watched by Victor Serge and Andr Breton (standing), Laurette Sjourn, and Jean Gemahling (with a stick). Vlady has his back to the camera. November 1940 [Chambon Foundation]

Victor Serge, probably on board the Presidente Trujillo sailing from Martinique to Santo Domingo [Chambon Foundation]

Victor Serge in Mexico, 1944

Laurette Sjourn in Mexico [Jeannine Kibalchich]

Leon Trotsky, Coyoacn, Mexico, 1940 [photograph A.H. Buchman]

Victor Serge in Mexico. Photo scratched, perhaps in anger?

Serges Mexican identity card

My fathers hand, Mexico, 1947, sketch by Vlady

Jeannine Kibalchich Russakova in 1982 [Jeannine Kibalchich]

Vlady and Irina Gogua, Moscow, 1989; their first reunion in fifty-seven years [photograph Susan Weissman]

Preface

This book aims to bring back to life the extraordinary commitment and hope of one of the great writer-thinker-activists of the twentieth century. Victor Serge is remembered for the intellectual richness and moral insight he brought to our understanding of the significant historical struggles of our time, as well as for the principled revolutionary life he exemplified. The journalist Daniel Singer wrote that Victor Serge devoted his life and brilliant pen to the revolution which for him knew no frontiers. An anarchist turned Bolshevik, he was unorthodox by nature, often a heretic but never a renegade. Serge lived in the maelstrom of the first half of the twentieth century, but his ideas are germane to current debates in our post-Soviet, post-Cold War world. His contribution is especially attractive today because Serge never compromised his commitment to the creation of a society that defends human freedom, enhances human dignity and improves the human condition. He belongs to our future.

Some readers may wonder how, more than a decade into the twenty-first century, the work of this almost forgotten revolutionary could have contemporary relevance. As the last century drew to a close, the Soviet Union collapsed, and with its demise the colossal battle of ideas it had provoked nearly disappeared from public discourse. How could the ideas and struggles that Serge represented, emerging from the titanic debates over the Russian Revolution and the society to which it gave birth, continue to resonate?

In fact, interest in Serges work experienced a stunning revival just as the Soviet Union was disintegrating, and is today in virtual renaissance his books are being published or re-published in many languages.political disputes of the disastrous Soviet experience, one is struck by the voice and testimony of Victor Serge. His works address the paramount and still unresolved issues of the day, as if he were speaking directly to this generation. Serge worried about how human beings could secure liberty, autonomy and dignity, and he belonged to a revolutionary generation that sought to create a society sufficient to realize these goals. They failed, but Serge spent the rest of his life elucidating the attempt, analysing the defeat and seeking better ways to the same ends. For that reason his life and work merits republication, analysis, interpretation and, above all, rescue.

Why rescue? The history of the Soviet experience is being rewritten by Cold Warriors and free-market dogmatists West and East who see early Bolshevism as no different from mature Stalinism. Both sides in the Cold War in a rather strange symbiosis thrived on this deliberate dishonesty in defining the nature and character of Communism, in theory and horrible practice. Both sides had an interest in distorting the ideas of the Soviet Left Opposition, who are once again being airbrushed from the platform of history. This book was written to rescue Serge from the margins and to redeem his reputation and his ideas, as well as to contribute in some small measure to correcting the historical record. Serge wasnt the only one nearly erased from historical memory, but he stands in this rendition as a clear representative of the ideas behind the October Revolution, ideas that fell by the wayside with the rise of Stalin.

The new editions of Victor Serges writings have been well received by leading contemporary intellectuals who recognize Serge as an important figure for the present. The American historian Walter Lacqueur finds the present Serge revival well deserved. Serges political recollections are very important because they reflect so well the mood of this lost generation [the small group of revolutionaries who were survivors of World War I]. His writings will find readers now because they help grant an understanding of the aftermath of the Russian Revolution and its impact on militants and intellectuals from what Lacqueur calls a world of yesterday almost as distant from subsequent generations as the Napoleonic wars. No longer invisible, Serges articles and books speak for themselves, and as Lacqueur concludes, we would be poorer without them.