For distributor details and how to order please visit the Ordering section on our website.

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations in critical articles or reviews, no part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without prior written permission from the publishers.

The rights of Paul Gordon as author have been asserted in accordance with the Copyright,

Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

We operate a distinctive and ethical publishing philosophy in all areas of our business, from our global network of authors to production and worldwide distribution.

Acknowledgements

This book simply would not have come into being without Gareth Evans. Love and thanks to him and to Melissa Benn and Graham Music for their encouragement and critical engagement; also to Hannah and Sarah, for being who they are. If I may borrow some words from Serge, I am grateful to them all for existing.

The music of Dino Saluzzi and Mal Waldron, brooding, tender, searching, endlessly evocative, provided the perfect soundtrack.

Paul Gordon

July 2012

Permissions

The quotations from Serges novels are used by kind permission of the translator, Richard Greeman. The lines from Serges poems are reprinted by kind permission of City Lights Books, translation (c) 1989 by James Brook. The lines from The Kingfishers are from Charles Olson, The Collected Poems of Charles Olson, Excluding the Maximus Poems. (c) 1987 by the Regents of the University of California, reprinted by kind permission of the University of California Press.

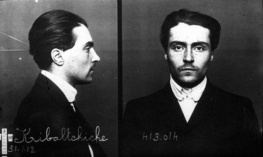

Victor Serge - a life line

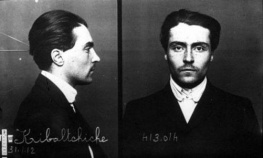

1890 - Born 30 December, Victor Lvovich Kibalchich, into Russian revolutionary migr family in Brussels

1912 - Sentenced to five years in French prison for association with armed anarchist gang

1915 - Marries Rirette Maitrejean

1917 - Released from prison, takes part in syndicalist uprising in Barcelona

Russian Revolution

1918 - Interned in concentration camp in France trying to get to Russia

1919 - Arrives in Petrograd to join the revolution, marries Liuba Russakova

1920 - Son, Vlady, born

1923 - Comintern agent in Berlin and Vienna

1924 - Death of Lenin, succession of Stalin

1928 - Expelled from Communist Party, begins writing fiction, Men in Prison (1930), Birth of our Power (1930) and Conquered City (1932), all published in France

1933 - Exiled to Orenburg, near Kazakhstan, writes Midnight in the Century (1939) and much of his poetry

1935 - Daughter, Jeannine, born

1936 - International solidarity campaign secures his exit from Soviet Union, lives in Brussels and Paris

1937 - Publishes Destiny of a Revolution and From Lenin to Stalin

1940 - Fall of France; assassination of Trotsky in Coyocoan, Mexico

1941 - Begins exile in Mexico where he writes three more novels, The Long Dusk, The Case of Comrade Tulayev and UnforgivingYears, and Memoirs of a Revolutionary, marries Laurette Sejourne

1947 - Dies of heart attack, 17 November, stateless, he is buried as a Spaniard in the French cemetery

Introduction:

the art of not dying away

Dazzling. That was the last word Victor Serge ever wrote. In his poem, Hands, a meditation on a sixteenth century terra cotta, which he had finished and typed up in the early hours of the day that would be his last. That evening, Tuesday 17 November 1947, he had gone out to see his artist son, Vlady, but he wasnt at home. He met Julian Gorkin, his old comrade, who had traveled from revolutionary Barcelona to greet him in Brussels when he was finally allowed to leave Russia. They talked for a bit before shaking hands and parting. Probably feeling unwell, he decided to take a cab home. His heart gave way before he even had time to tell the driver where he wanted to go.

Gorkin went to the police station to identify him just after midnight:

In a bare shabby room with grey walls, he was laid out on an old operating table, wearing a threadbare suit and a workers shirt, with holes in his shoes. A cloth bandage covered the mouth that all the tyrannies of the century had not been able to shut. One might have thought him a vagabond who had been taken in out of charity. In fact, had he not been an eternal vagabond of life in search of the ideal? His face still bore the stamp of bitter irony, an expression of protest

He had arrived here six years before with Vlady - his companion, Laurette, and his daughter, Jeannine, would come later - fleeing from Nazi-occupied Europe, leaving behind a lifetime of political activity - an anarchist in France, a syndicalist in Spain, a critical Bolshevik in Russia, an agent of the Comintern in Germany and Austria, years of internal exile in Russia, a supporter of the revolutionary POUM in Spain, of which Gorkin had been one of the leaders. The journey had taken six months on a cargo ship he described as an ersatz concentration camp of the sea. There were more than 300 of them on it, including the surrealist Andre Breton, with whom Serge had campaigned in Paris against the Stalinist show-trials, and Bretons wife, Jacqueline. Oddly, the passengers included the anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss, on his way to a new post in New York. Levi-Strauss was clearly in awe of Serge: he was a man, after all, who had known Lenin, but he found his physical presence at odds with his preconceptions. more like an elderly and spinster aunt with an asexual quality very far removed from the virile and superabundant vitality commonly associated with subversive activities. This, surely, says more about Levi-Strauss than it does about Serge. (Although he complained, Levi-Strauss traveled in comparative comfort compared to most of the passengers, as he was one of the few to have the use of the ships two cabins.)

By stark contrast, the young man who would become Mexicos greatest writer and who would eventually win the Nobel Prize, Octavio Paz, had met Serge in Paris not long before and was immediately and powerfully drawn to him. I spent hours talking with him, he recalled. Serges human warmth, his directness and generosity, could not have been further from the pedantry of the dialecticians. A moist intelligence. In spite of his sufferings, setbacks. and long years of arid political arguments, he had managed to preserve his humanity. I was not moved by his ideas, but by his person an example of the fusion of two opposing qualities: moral and intellectual intransigence with tolerance and compassion. (It was Serge who introduced Paz to the work of the French painter/writer, Henri Michaux, a discovery of capital importance for me.)

Their journey involved yet another period in prison (this time in French-run Martinique) and, then bizarrely, his first ever flight in a plane. Mexico was not his choice but there was nowhere else, and it had become a home of sorts to thousands of political refugees, thanks to Lazaro Cardenas, the former president whose government was one of the few to have supported the Republican side in Spain, and opened the country to many Spanish and other exiles.