Victor Serge - Victor Serge: Year One of the Russian Revolution

Here you can read online Victor Serge - Victor Serge: Year One of the Russian Revolution full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. genre: Romance novel. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

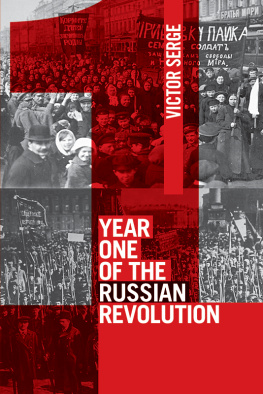

- Book:Victor Serge: Year One of the Russian Revolution

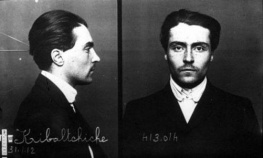

- Author:

- Genre:

- Rating:3 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Victor Serge: Year One of the Russian Revolution: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Victor Serge: Year One of the Russian Revolution" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Victor Serge: Year One of the Russian Revolution — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Victor Serge: Year One of the Russian Revolution" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Sequences in world history are so tightly interconnected that it is often necessary to go back a long while in order to get some more than arbitrary idea of the causes of an event especially when the event concerned is as grandiose as the Russian revolution.

The close of the eighteenth and the first half of the nineteenth century are marked in the history of western Europe by a social transformation which is painful, radical and pregnant with immense possibilities: the bourgeois revolution.

The ancien-rgime monarchies were the heirs of the feudal system over which they had triumphed in the bloody struggles of an earlier age, aided by the people of the communes, a revolutionary force of their time. These kingdoms rested on large-scale landed property (noble or feudal), on the bureaucratic absolutism of the royal dynasty, and on the hierarchy of orders in the realm, with the nobility and clergy taking precedence over the bourgeoisie. Of these social classes, the older dominant orders were in a state of decline and the other, the bourgeoisie of commerce, manufacturing, finance and parliament, was sinking powerful roots among the lower artisan classes, and developing traditions of work, thrift, business honesty, dignity and political liberty the latter, as always, being greatly valued among the subject classes of society. Growing in strength and in the consciousness of its own needs and principally of the necessity to sweep away all obstacles in the way of its own advancement the bourgeoisie was making its way towards power. The French Revolution of 1789-93 opened the series of bourgeois revolutions. What is the Third Estate [meaning the bourgeoisie]? the Abb Sieyes, one of the future men of Thermidor and Brumaire, speculated in 1789. Nothing. What must it become? Everything.

It took until about 1850 to complete the bourgeois revolution in Europe. Napoleons armies carried it from Madrid and Lisbon as far as Vienna and Berlin. The revolutions of 1830 and 1848 are its final political convulsions. In the meantime, the industrial revolution had begun, a revolution perhaps even more radical (the first steam-engine, that produced by Watt, dates from 1769; Fulton invents the steamboat in 1807 and Stephenson the locomotive in 1830; Jacquards loom is from 1802). Large-scale mechanized industry, with assistance from the railways, fills the cities of work and misery with a new transforming force: the proletariat. Hot in the steps of the bourgeois revolution characterized by the abolition of feudal privileges and the system of monarch, nobles and castes, the conquest of the freedoms necessary for industrial the social hegemony of the bourgeoisie and the omnipotence of money fresh battles break out in the newly won terrain: the proletariat, even before it recognizes its mission as the liberator of humanity, demands its right to a human existence.

Throughout the first half of the nineteenth century, Russia remains outside the influence of the revolutionary convulsions in the West. The ancien rgime (serfdom, privileges of nobility and Church, Tsarist autocracy) is here impregnable: the Decembrist military conspiracy of 1825 scarcely ruffles it. From 1840 onwards, the need for serious reform does begin to be apparent: agricultural production is poor, grain exports low, the growth of manufacturing industry slowed down through the shortage of labour; capitalist development is being impeded through aristocracy and serfdom. It is a perilous situation, which is given a fairly astute solution in the act of liberation of 19 February 1861, abolishing serfdom. The emancipated peasant now has to buy up tiny, neatly truncated plots of land, and passes from a feudal subjection to an economic one. He must now work harder, and manufacturing industry will find in the countryside the free manpower it needs so badly. With a population of sixty-seven million in this epoch, Russia had twenty-three million serfs belonging to 103,000 land-lords. The arable land which the freed peasantry had to rent or buy was valued at about double its real value (342 million roubles instead of 180 million); yesterdays serfs discovered that, in becoming free, they were now hopelessly in debt. Between this great reform of Alexander II, the Tsar Liberator, and the revolution of 1905, the lot of Russias peasants will worsen uninterruptedly. The reform of 1861 gave them about five hectares of land per male inhabitant; by 1900 the rapid population increase will leave the muzhiks with less than three hectares per head seventy per cent of the farmers possessed an area of cultivation below the minimum needed to support, their families. On the other hand, in 1876, fifteen years after the reform, the export sales of Russian grain on the European market had risen by 140 per cent, causing a fall in the world price of cereals. In 1857-9 Russia exports only 8,750,000 quarters (English measure) of cereal crops; in 1871-2 it exports 21,080,000. For commerce, for industry, for landed property and for the governing bureaucracy, the emancipation of the serfs was good business. The peasants simply exchanged one form of slavery for another and became subject to periodic famines.

The abolition of serfdom in Russia coincides with the War of Secession and the abolition of slavery in the United States of America (1861-3). Both in the Old World and the New, the growth of capitalism demands the replacement of the slave or serf by the free worker free, that is, to sell his toil. The free worker works better, more intensively and more conscientiously. Large mechanized industry is incompatible with primitive methods of compulsion; in their place it substitutes economic constraint, the concealed compulsion of hunger whose efficacy is different in nature from that of naked violence.

At the very time when his great reform was being implemented, in the year 1863, the Tsar Liberator crushed the Polish rising in the blood of its patriots: there were 1,468 executions.

The initial path of capitalist development in Russia may have been cleared by the reform of 1861, but the way ahead for it was not without obstacles. There was no equality of civil rights. Initiative was clogged by a rigid bureaucratic and police apparatus. Privileged castes maintained their position in the State; the bourgeoisie was kept at a distance from the levers of power, and saw its interests (which it sincerely identified with the general interests of progress) constantly misrepresented by reactionary values, or else sacrificed to the demands of the Tsarist court, the nobility or the big landlords.

Disturbances among the peasantry became a constant problem. Within the petty-bourgeoisie, deprived of any rights or assured future, and mauled both by the old rgime and by ascendant capitalism, the young intelligentsia had become captivated by the advanced ideas of the West, and promised to be a favourable ground for the seeds of revolution. New reforms, such as the reorganization of the judiciary, the statute on local governments and the abolition of corporal punishment, co-existed with pitiless acts of repression such as the deportation of the thinker Chernyshevsky to Siberia, where he spent twenty years. The first important revolutionary movement in Russia, that of the Narodniki or Populists (from the word narod, meaning people), was impelled by a number of factors: the weakness of the Russian bourgeoisie proper, which constantly tended towards compromise with reaction; the non-existence of any liberal movement; the desperate plight of the peasantry, the common people and the propertyless intellectuals; the rigours of repression and the influence of Western Socialism, with its heritage from the revolutionary tradition of 1848. The Narodniki hoped for a popular revolution and saw the old Russian rural commune, or

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Victor Serge: Year One of the Russian Revolution»

Look at similar books to Victor Serge: Year One of the Russian Revolution. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Victor Serge: Year One of the Russian Revolution and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.