Anarchists Never Surrender: Essays, Polemics, and Correspondence on Anarchism, 19081938

Victor Serge. Edited and Translated by Mitchell Abidor.

Foreword by Richard Greeman

This edition copyright 2015 PM Press

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be transmitted by any means without permission in writing from the publisher.

This book has been made possible in part by a generous donation from the Anarchist Archives Project

ISBN: 978-1-62963-031-1

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014908074

Cover by John Yates/Stealworks

Interior design by briandesign

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

PM Press

PO Box 23912

Oakland, CA 94623

www.pmpress.org

Printed in the USA by the Employee Owners of Thomson-Shore in

Dexter, Michigan. www.thomsonshore.com

Contents

| by Richard Greeman |

| by Mitchell Abidor |

Meditation on a Maverick

by Richard Greeman

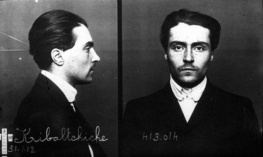

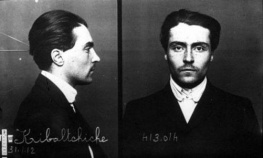

ANARCHISTS NEVER SURRENDER! WHAT AN APT TITLE MITCH ABIDOR HAS chosen for his beautifully translated anthology of the anarchist writings of Victor Lvovitch Kibalchich, aka Victor Serge (18901947), who up to the age of twenty-eight wrote and agitated under the pseudonym Le Rtif (Maverick).

The phrase Anarchists Never Surrender! comes from a 1909 Maverick article, written at the age of eighteen, and the anarchists in question, like Kibalchich himself, were Russian exiles, resolute bandits who fought to the death against a whole squad of London policemen. Mavericks dramatic declaration foreshadowed his own and his comrades doom in the Tragic Bandits affair a few years later in Paris. Indeed, Victor Kibalchich may be said to have inherited that fate, as he bore the famous name of N.I. Kibalchich, a distant relative, the Peoples Will terrorist whose bombs blew up the Czar, executed in 1881 and considered a martyr-hero by Victors parents.

Victors whole life was to be one of constant rebellion and constant persecution, and he already had a head start at birth. He spent more than ten of his fifty-seven years in various forms of captivity, generally harsh. He did five years straight time (191217) in a French penitentiary (anarchist bandit); survived nearly two years (191718) in World War I concentration camp (Bolshevik suspect); suffered three months grueling interrogation in Moscows notorious GPU Lubianka prison (Trotskyite spy); and endured three years deportation to Central Asia for his declared opposition to Stalins policies and for refusing to confess to trumped-up espionage charges (193336). Small wonder his first novel (written in French) bore the title Men in Prison.

Born of Russian exile parents camped out in Brussels, Victor was a stateless, undocumented alien from birth, destined to be expelled from nearly every country he ever lived in. He was thus vaccinated against the plague of nationalism and remained immune to the patriotic fever that swept away many socialists and anarchists at the outbreak of World War I in 1914. Young Kibalchich inherited the revolutionary ethos of the Russian intelligentsia, and little else from his penniless parents when they split up, leaving him on his own in Brussels at the age of fifteen. There, he bonded with a gang of teenagers, idealistic underpaid apprentices like himself, closer than brothers. The Brussels brothers started out as Socialist Young Guards but soon grew impatient with reformism and gravitated to anarchism, impressed with the free life at a short-lived anarchist Commune just outside of Brussels. There they learned the printing trades and eventually put out their own little sheet, The Rebel, where Victor first cut his teeth as a writer and adopted the name Maverick, symbolizing his distance from the tradition of his Russian parents and his embrace of an angry new anarchist identity in the slum streets of Brussels. Maverick was the signature on the articles in the first part of this anthology, starting in 1908 and continuing throughout Victors young manhood to 1917, the year of the Russian Revolution, when Kibalchich started signing Victor Serge and decided to go to Russia.

Meanwhile, as Maverick he moved to Paris in 1909 and eventually became the editor of the weekly organ of French anarcho-individualism, lanarchie, which preached, among other things, the right of individuals to reappropriate property from the bourgeois bandits who had, after all, stolen it in the first place (Proudhon: property = theft). A perfect theory, until Victors band of brothers, in total revolt against society and unwilling to be either masters or slaves, began to put it into practice in 1912 through a bloody series of expropriations (holdups) in which they pioneered the use of stolen automobiles as getaway cars (the police had only bicycles). Victor/Maverick, although appalled by the bloodshed, defended these Tragic Bandits of Anarchy in the pages of lanarchie, declaring, I am with the wolves! He was soon arrested. Like the Russian anarchists in London, Mavericks home-boys fought it out to the last, holding off small armies of police, troops, and armed civilians. In 1913, the survivors of what was known as the Bonnot Gang were put on trial. Victors oldest friend got the guillotine, and Maverick was sentenced to five years in solitary in the pen. He managed to survive, That is the context of the early (19081913) articles in this collection.

Released in the middle of World War I and expelled from France, Victor ended up in Barcelona, Spain. There he got involved with the local anarcho-syndicalists and participated in the preparation of an insurrectionary general strike in July 1917, itself inspired by the February 1917 Revolution in Russia which seemed to beckon to Victor from across wartorn Europe. He laid to rest his individualist identity of The Maverick, and began signing himself Victor Serge, the identity that he would retain for the rest of his life. The Parisian individualist who scorned revolutions as illusions, had now experienced a revolutionary movement in Spain and felt himself drawn to the Russian Revolution as to a flame. Yet we can see in the two articles from 1917 that he was still settling his scores with anarcho-individualism in his mind. And indeed, as Serge he retained the essence of his anarchismthe belief in the primacy of the individual, in human freedomto his dying day.

Arriving in Petrograd, the frozen, starving, besieged capital of Red Russia, Serge made the rounds of the anarchists and socialists before deciding to work with the Bolsheviks as the only practical way to serve the living revolution while hoping to influence it in a libertarian direction once victory was won. The newly founded Communist International immediately put to use Serges talents as a writer, translator, and printer, and at a crucial moment in the Civil War, when all seemed lost, he joined the Communist Party, the better to serve the cause. In this, he had much in common with other Soviet anarchists, including the Americans Bill Chatov and Big Bill Haywood.

This was the period when Lenin was wooing the best elements among the anarchists and anarcho-syndicalists of Europe to the Communist International, and Serges reports, published in France, were part of that Soviet propaganda campaign. For example Serges 1920 The Anarchists and the Russian Revolution,by calling upon his fellow anarchists to join with the Communists and to strive to preserve the spirit of liberty.

They will be the enemies of the ambitious, of budding political careerists and commissars, of formalists, party dogmatists and intriguers, in other words to fight the illusions of power, to foresee and forestall the crystallization of the workers state as it has emerged from war and revolution, everywhere and always to encourage the initiative of individuals and of the masses, to recall to those who might forget that the dictatorship is a weapon, a means, an expedient, a necessary evilbut never an aim or a final goal.

Next page