The automobile used in the robbery.

The holdup at the Socit Gnrale, rue Ordener, Paris. The courier Ernest Caby is shot by one of the bandits.

Peemans was unharmed and ran into the bank, shouting, They are attacking our courier! Several bank employees followed Peemans out into the street in time to see the man fire a fourth shot, which lodged near Cabys spine. The gunman then grabbed one of Cabys bags; another man grabbed a second sack. Both men jumped back into the waiting car, leaving Caby lying in a pool of blood.

Two municipal policemen ( gardiens de la paix ) arrived from different directions and moved toward the automobile, but they were met by a barrage of shots fired from inside the Delaunay-Belleville as it sped off. A bus arrived, blocking the street at the corner of the rue du Cloys, and a tram was crossing the road, but the driver of the speeding automobile skillfully avoided both and turned onto rue Montcalm and then onto rue Vauvenargues and headed out of Paris via the porte de Clichy. No one managed to stop them before they made their escape.

News of the holdup and shooting at the Socit Gnrale exploded in Paris. Although it was the first holdup in France using an automobile, it confirmed public worries about the use of automobiles in burglaries to elude the police. In this case the thieves were better armed and better equipped than the authorities. The police had very few automobiles at their disposal. Caby, who survived, was the only casualty, but the holdup was an embarrassment for the police.

From his office on the le de la Cit, Louis Lpine, who had been the prefect of police since 1893, moved quickly to coordinate the massive police operation intended to find the bandits. Born in Lyon in 1846 into a family of modest origin, Lpine had quickly given up law for administration, serving in Saint-tienne as prefect of the Loire. The Prefecture of Police of Paris had been created in 1800 and charged with all that concerns the police, in the widest possible sense. Louis Lpines post was therefore an important position in the hierarchy of power in France. This position enabled him, as it had his predecessors, to intervene arbitrarily, forcefully, and sometimes secretly on the edge of illegality in the investigation of crimes, ordering arrests and searches as he pleased, dipping into an enormous drawer of secret funds that enabled him to pay off informers and police spies. Lpine knew how to manipulate the municipal council of Paris; he had staked his reputation on his ability to prevail in negotiations with anyone who might check his power. He imagined himself to be the king of Paris, or the commander by divine right, imposing military discipline on his agents, his brigades, and his administration. As he sat behind his large deskwith his mustache and short beard, invariably wearing a dark suit and tie, matched by a black top hat when he went outLpine had no idea who might have carried out the audacious attack on the courier who worked for Socit Gnrale. But his attention soon turned to the possibility that anarchists were involved.

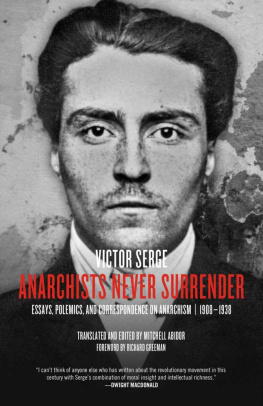

The next morning, in their small apartment in plebeian Belleville, Victor Kibaltchiche, the Brussels-born anarchist son of Russian migrs, and his companion Rirette Matrejean, a fellow anarchist who had come to Paris from her village in central France, read in the newspapers about the dramatic, bloody theft and getaway. Victor immediately thought of someone who might have done it: a certain Jules Bonnot, whom Victor and Rirette had recently met in anarchist circlesHe is crazy enough to have done that! Victor and Rirette read the descriptions of the perpetrators. For her part, Rirette doubted that a man whom eyewitnesses described as being small with a thin mustache could have been Bonnot. Victor disagreed. And another accomplice had been described as seeming very young, not very big, wearing a martingale raincoat, a melon-shaped hat, binocles, and with a face of baby-like rose complexion. Victor immediately recognized Raymond Callemin, once a close friend from his youth in Brussels. Eyewitness accounts led Victor to believe that another Belgian, a violent anarchist named Octave Garnier, was one of the fouror fivemen whom passersby had seen in the car. Victor and Rirette realized that although they had had absolutely nothing