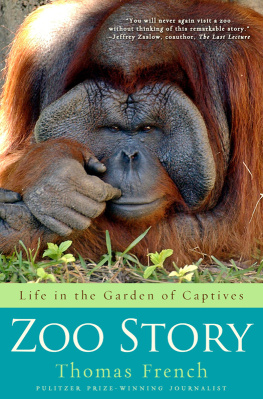

I know zoos are no longer in peoples good graces.

Religion faces the same problem.

Certain illusions about freedom plague them both.

Chapter 1

The New World

Eleven elephants. One plane. Hurtling together across the sky.

The scene sounds like a dream conjured by Dal. And yet there it was, playing out high above the Atlantic. Inside the belly of a Boeing 747, eleven young elephants were several hours into a marathon flight from South Africa to the United States. Nothing could have prepared them for what they were experiencing. These were not circus animals, accustomed to captivity. All of these elephants were wild, extracted at great expense and through staggering logistics from their herds inside game reserves in Swaziland. All were headed for zoos in San Diego and Tampa.

The date was August 21, 2003, a Thursday morning that stretched on and on. The elephants were confined in eleven metal crates inside the semidarkness of the freighter jets cavernous hold. Before they were loaded into the plane, they had been sedated. Now they were woozy and not particularly hungry. Some lay on their sides, slumbering. A few stood and snaked their trunks toward a human who moved up and down the line of crates, replenishing their water, murmuring reassurance.

Calm down, Mick Reilly told them. Its not so bad.

Mick was thirty-two, with light brown hair and the permanent tan of someone who has grown up in the African bush. As usual, he was clad in his safari khakis and an air of quiet self-assurance. His arms and legs bore the faint scratches of acacia thorns. His weathered boots were powdered with the red dust of the veldt. Everything about him testified to a lifetime of wading through waist-high turpentine grass and thickets of aloe and leadwood trees, of tracking lions and buffalos and rhinos and carefully counting their young, of hunting poachers armed with AK-47s.

Mick and his father ran the two game reserves where the elephants had lived in Swaziland, a small landlocked kingdom nestled in the southern tip of Africa. Mick and these eleven elephants had come of age together in the parks. They recognized his scent and voice, the rhythms of his speech. He knew their names and histories and temperamentswhich of them was excitable and which more serene, where each of them ranked in the hierarchies of their herds. Watching them in their crates, he could not help but wonder what they were thinking. Surely they could hear the thrum of the jet engines and feel the changes in altitude and air pressure. Through the pads of their feet, equipped with nerve endings highly attuned to seismic information, they would have had no trouble detecting the vibrations from the fuselage. But what could they decipher from this multitude of sensations? Did they have any notion that they were flying?

Its OK, Mick told them. Youll be fine.

Not everyone, he realized, agreed with his assessment. He was tired of the long and bitter debate that had raged on both sides of the Atlantic in the months before this flight. Tired of the petitions and the lawsuits and the denunciations from people who had never set foot in Swaziland, never seen for themselves what was happening inside the game reserves. There simply was not enough room for all of the elephants anymore, not without having the trees destroyed, the parks devastated, and other species threatened. Either some of the elephants had to be killed, or they could be sent to new homes in these two zoos. Mick saw no other way to save them. He had heard the protests from the animal-rights groups, insisting that for the elephants any fate would be preferable to a zoo, that it would be better for them to die free than live as captives.

Such logic made him shake his head. The righteous declarations. All this talk of freedom as if it were some pure and limitless river flowing through the wild, providing for every creature and allowing them all to live in harmony. On an overcrowded planet, where open land is disappearing and more species slip toward extinction every day, freedom is not so easily defined. Should one speciesany specieshave the right to multiply and consume at will, even as it nudges others toward oblivion?

As far as Mick could tell, nature cared about survival, not ideology. And on this plane, the elephants had been given a chance. Before his family had agreed to send them to the two zoos, he had visited the facilities where they would be housed and had talked with the keepers who would care for them. He was confident the elephants would be treated humanely and be given as much space to move as possible. Still, there was no telling how they would adjust to being taken from everything they knew. Wild elephants are accustomed to ranging through the bush for miles a day. They are intelligent, self-aware, emotional animals. They bond. They rage and grieve. True to their reputation, they remember.

How would the exiles react when they realized their days and nights were encircled as never before? When they understood, as much as they could, that they would not see Africa again? Either they had been rescued or enslaved. Or both.

The 747 raced westward, carrying its living cargo toward the new world.

The savanna, alive just after sunset. Anvil bats search for fruit in the falling light. A bush baby wails somewhere in the trees. Far off to the east, along the Mozambique border, the Lebombo Mountains stand shrouded in black velvet.

A fat moon, nearly full, shines down on a throng of elephants chewing their way through whats left of the umbrella acacias inside Mkhaya Game Reserve. A small patch of green in the center of Swaziland, Mkhaya is one of the parks the elephants on the 747 were taken from. This was their home. Before deciding what to think about the fate of the eleven headed for the zoos, it helps to see the wild place they came from. To know what their lives were like before they ended up on the plane and to understand the realities that pushed them toward that surreal journey.

An evening tour through Mkhaya is especially dramaticclimbing into a Land Rover at the end of a golden afternoon, then lurching along the parks winding dirt roads, searching for the elephants who remain. Mkhayas herd is a good-sized groupsixteen in all, counting the calvesand even though they are the largest land mammals on earth, they are not always easy to find. Elephants, it turns out, are surprisingly stealthy.

As the sunlight fades, other species declare their presence. Throngs of zebras and wildebeests thunder by in the distance, trailing dust clouds. Cape buffalo snort and raise their horns and position themselves in front of their young. Giraffes stare over treetops, their huge brown eyes blinking, then lope away in seeming slow motion. But no elephants.