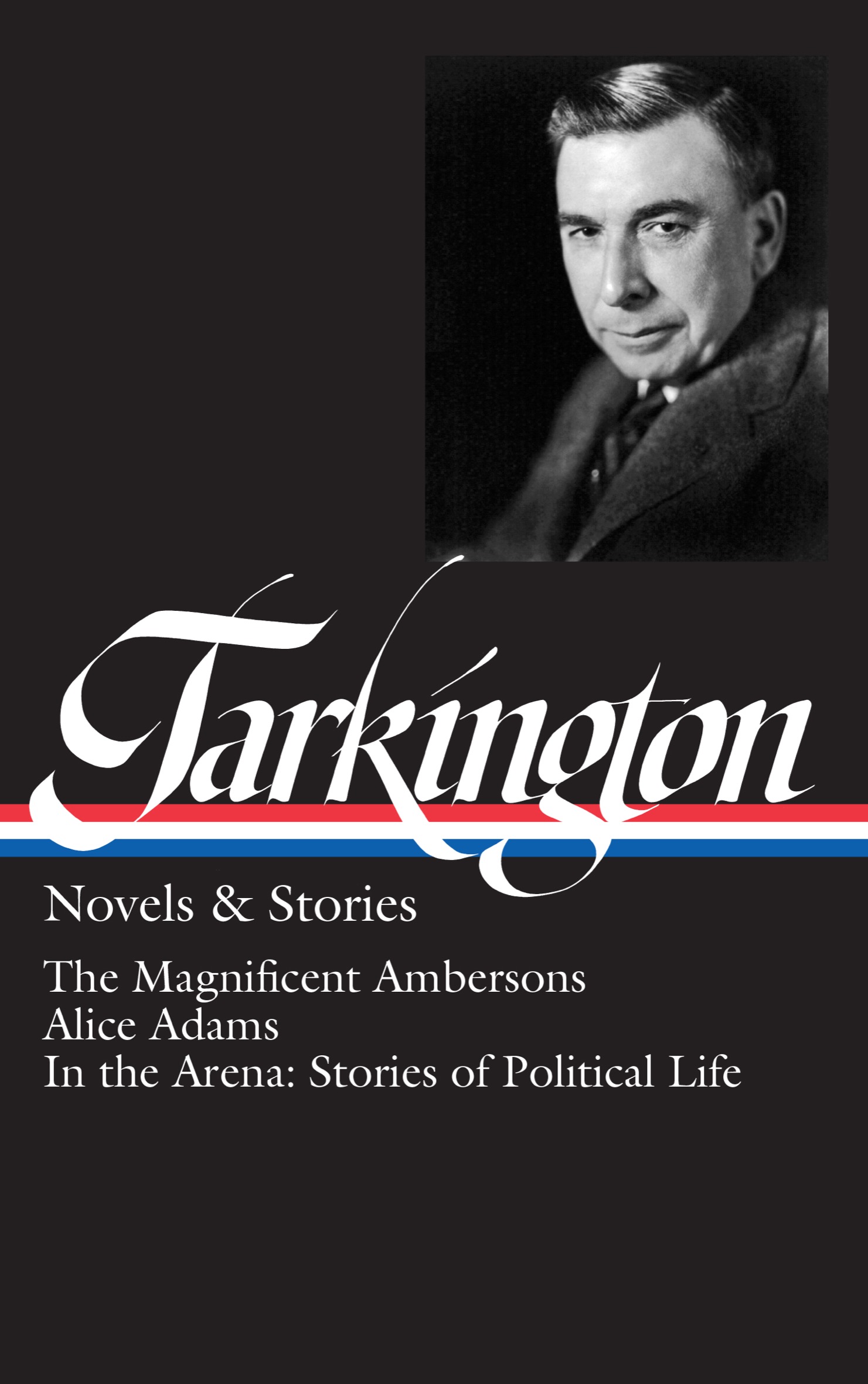

B OOTH T ARKINGTON

NOVELS & STORIES

The Magnificent Ambersons

Alice Adams

In the Arena: Stories of Political Life

Thomas Mallon, editor

LIBRARY OF AMERICA E-BOOK CLASSICS

BOOTH TARKINGTON: NOVELS & STORIES

Volume compilation, notes, and chronology copyright 2019 by

Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., New York, N.Y.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without

the permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief

quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Published in the United States by Library of America

LIBRARY OF AMERICA, a nonprofit publisher,

is dedicated to publishing, and keeping in print,

authoritative editions of Americas best and most

significant writing. Each year the Library adds new

volumes to its collection of essential works by Americas

foremost novelists, poets, essayists, journalists, and statesmen.

Visit our website at www.loa.org to find out more about

Library of America, and to sign up to receive our

occasional newsletter with exclusive interviews with

Library of America authors and editors, and our popular

Story of the Week e-mails.

eISBN 9781598536218

Contents

THE MAGNIFICENT AMBERSONS

To Susanah

Chapter I

M AJOR AMBERSON had made a fortune in 1873, when other people were losing fortunes, and the magnificence of the Ambersons began then. Magnificence, like the size of a fortune, is always comparative, as even may now perceive, if he has happened to haunt New York in 1916; and the Ambersons were magnificent in their day and place. Their splendour lasted throughout all the years that saw their Midland town spread and darken into a city, but reached its topmost during the period when every prosperous family with children kept a Newfoundland dog.

In that town, in those days, all the women who wore silk or velvet knew all the other women who wore silk or velvet, and when there was a new purchase of sealskin, sick people were got to windows to see it go by. Trotters were out, in the winter afternoons, racing light sleighs on National Avenue and Tennessee Street; everybody recognized both the trotters and the drivers; and again knew them as well on summer evenings, when slim buggies whizzed by in renewals of the snow-time rivalry. For that matter, everybody knew everybody elses family horse-and-carriage, could identify such a silhouette half a mile down the street, and thereby was sure who was going to market, or to a reception, or coming home from office or store to noon dinner or evening supper.

During the earlier years of this period, elegance of personal appearance was believed to rest more upon the texture of garments than upon their shaping. A silk dress needed no remodelling when it was a year or so old; it remained distinguished by merely remaining silk. Old men and governors wore broadcloth; full dress was broadcloth with doeskin trousers; and there were seen men of all ages to whom a hat meant only that rigid, tall silk thing known to impudence as a stove-pipe. In town and country these men would wear no other hat, and, without self-consciousness, they went rowing in such hats.

Shifting fashions of shape replaced aristocracy of texture: dressmakers, shoemakers, hatmakers, and tailors, increasing in cunning and in power, found means to make new clothes old. The long contagion of the Derby hat arrived: one season the crown of this hat would be a bucket; the next it would be a spoon. Every house still kept its bootjack, but high-topped boots gave way to shoes and ; and these were played through fashions that shaped them now with toes like box-ends and now with toes like the prows of racing shells.

Trousers with a crease were considered plebeian; the crease proved that the garment had lain upon a shelf, and hence was ready-made; these betraying trousers were called hand-me-downs, in allusion to the shelf. In the early eighties, while bangs and bustles were having their way with women, that variation of dandy known as the dude was invented: he wore trousers as tight as stockings, dagger-pointed shoes, a spoon Derby, a single-breasted coat called a Chesterfield, with short flaring skirts, a torturing cylindrical collar, laundered to a polish and three inches high, while his other neckgear might be a heavy, puffed cravat or a tiny bow fit for a dolls braids. With evening dress he wore a tan overcoat so short that his black coat-tails hung visible, five inches below the overcoat; but after a season or two he lengthened his overcoat till it touched his heels, and he passed out of his tight trousers into trousers like great bags. Then, presently, he was seen no more, though the word that had been coined for him remained in the vocabularies of the impertinent.

It was a hairier day than this. Beards were to the wearers fancy, and things as strange as the blew like tippets over young shoulders; moustaches were trained as lambrequins over forgotten mouths; and it was possible for a Senator of the United States to wear a mist of white whisker upon his throat only, not a newspaper in the land finding the ornament distinguished enough to warrant a lampoon. Surely no more is needed to prove that so short a time ago we were living in another age!

... At the beginning of the Ambersons great period most of the houses of the Midland town were of a pleasant architecture. They lacked style, but also lacked pretentiousness, and whatever does not pretend at all has style enough. They stood in commodious yards, well shaded by leftover forest trees, elm and walnut and beech, with here and there a line of tall sycamores where the land had been made by filling bayous from the creek. The house of a prominent resident, facing Military Square, or National Avenue, or Tennessee Street, was built of brick upon a stone foundation, or of wood upon a brick foundation. Usually it had a front porch and a back porch; often a side porch, too. There was a front hall; there was a side hall; and sometimes a back hall. From the front hall opened three rooms, the parlour, the sitting room, and the library; and the library could show warrant to its titlefor some reason these people bought books. Commonly, the family sat more in the library than in the sitting room, while callers, when they came formally, were kept to the parlour, a place of formidable polish and discomfort. The upholstery of the library furniture was a little shabby; but the hostile chairs and sofa of the parlour always looked new. For all the wear and tear they got they should have lasted a thousand years.

Upstairs were the bedrooms; mother-and-fathers room the largest; a smaller room for one or two sons, another for one or two daughters; each of these rooms containing a double bed, a washstand, a bureau, a wardrobe, a little table, a rocking-chair, and often a chair or two that had been slightly damaged downstairs, but not enough to justify either the expense of repair or decisive abandonment in the attic. And there was always a spare-room, for visitors (where the sewing-machine usually was kept), and during the seventies there developed an appreciation of the necessity for a bathroom. Therefore the architects placed bathrooms in the new houses, and the older houses tore out a cupboard or two, set up a boiler beside the kitchen stove, and sought a new godliness, each with its own bathroom. The great American plumber joke, that many-branched evergreen, was planted at this time.