THE TATAS

How a Family Built a

Business and a Nation

GIRISH KUBER

Translated from the Marathi by

Vikrant Pande

J.R.D. Tata used to say, Live life a little dangerously.

This book is dedicated to all those who live by this perilous principle and have immersed themselves in wealth creation for the greater good of society against all odds.

Contents

Authors Note

Preface

Nusserwanji of Navsari

The Man Who Sowed Dreams

The Glow after the Sunset

Son of the Sun

The Dawn of the Industrial Age

Jehangirs World

Baptism by Fire

J.R.D. Tata: Chairman, Tata Sons

Independence Dawns

Air India and Free India

New Ventures

Air India Is Nationalized: A Devastating Decline Begins

Stressful Times

Naval Ratanji Tata and JRD

A Question of Succession

JRD: The Twilight Years

Ratan Tata: New Directions, New Challenges

Settling Down as Chairman of Tata Sons

The Birth of a Motor Car

Tata Finance Ltd and the Dilip Pendse Case

Building Tata Consultancy Services

Small Car, Big Trouble

The Tata Culture

The Search for a Successor

The Storm and a New Beginning

An Interview with Ratan Tata

Bibliography

Index

Acknowledgements

Photographic Inserts

About the Book

About the Author and Translator

Copyright

Authors Note

The narrative of The Tatas spans almost 200 years. In condensing it to a 250-odd-page story with a popular appeal for the lay reader, I have re-imagined and reconstructed some scenes and conversations. This is also a work of translation from Marathi to English. As such, the words written may not be exactly the ones spoken, yet they are true to the meaning of the conversations drawn from the sources listed at the end of the book. While the translator, the editor and I have made every effort to ensure that the translation is as faithful to the original sources as possible, some inadvertent discrepancies may have nevertheless survived to the final draft. Any errors are deeply regretted.

Preface

Why have I written a book on the Tatas and why now? The answer is simple.

The Tata conglomerate is intricately intertwined in so many of Indias successes and firsts, and most of these, incredibly, have remained uncovered. Not many know that it was the Tatas who brought silk to Mysore or that they were the ones who got strawberries to Mahabaleshwar, a popular hill station in Maharashtra now synonymous with the fruit. Not many are aware, either, that the worlds earliest worker welfare policies were drafted in a Tata venture or that the Tatas were global pioneers in conceiving a hydroelectric project.

Though much has been written about the Tatas, it has been mostly from a corporate or industry-specific perspective, such as on Tata Steel or Tata Consultancy Services (TCS). My effort here is to tell the human side of this business story, from the common mans point of view, without resorting to jargon and mind-boggling numbers.

And there is a need to tell this story as there is a growing trend all over the world of measuring success purely on the basis of balance sheets. Profits do matter, no doubt, but thats not the only factor. Against this backdrop, it is fascinating to delve into this story that starts with a common Indian middle-class man who aimed high and, while achieving what he set his sights on, thought of what he could do for the country and cared for the environment. Whatever the Tatas did, it wasnt solely with profitability in mind. The Tatas did not just build companies, they also lent a huge hand in building the nation.

There are few stories of homegrown Indian business houses that have a global appeal. The story of the Tatas is one of them.

I wrote this book in Marathi as Tatayan about five years ago. The response to it was overwhelming. There have been a dozen reprints to date. From politicians of all hues to businessmen to readers from different walks of life, it touched every section of society. The most important reason behind the books success, I feel, is the fascination Indians have for the Tatas. Incidentally, Tatayan is also the only book that chronicles the Tata story right from its inception about 200 years ago to now. That may be the other reason behind the books sustained popularity. For Tatayan , I owe a big thank you to Mr Dilip Majgaonkar of Rajhans Prakashan, who took personal interest in producing it with lan.

I am equally thankful to Siddhesh Inamdar, Commissioning Editor at HarperCollins, for spotting the book, and to the HarperCollins team for deciding to take it to an English readership. The Tatas would not have been published without Siddheshs active involvement.

I must also thank Vikrant Pande for the tremendous work he put in to translate the book into English, and Amit Malhotra for the cover design that perfectly captures the steely resolve associated with the Tatas.

I hope the book leaves readers feeling as inspired and invigorated as I felt writing it.

Girish Kuber

Mumbai

February 2019

CHAPTER

Nusserwanji of Navsari

T his boy is going to rule the world. He will be rich enough to build a seven-storey bungalow, prophesied the astrologer and quite predictably got a nice offering for himself.

One expects to hear such things at a naming ceremony, mumbled an elder, but the women, warding off the evil eye, waved their palms over the baby boys face and cracked their knuckles. The boy was named Nusserwan, and no one bothered too much thereafter about what the astrologer had said. Nearly everybody in Navsari, including the ragged little urchins populating its dusty streets, had been foretold a glorious future.

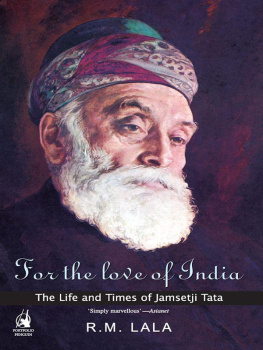

Nusserwanji Tata, however, was to prove the astrologer right.

THE EARLY YEARS

Young Nusserwanji, born in 1822, was raised in a priestly household. His father would daily don prayer whites, pray and read from the Zend Avesta. His childhood was similar to that of his friends, which included being married off even before one learnt to walk properly. Thereafter, the bridegrooms attended school, their brides having been sent home to grow up. The couples were reunited once they attained puberty, only to separate often when the wives went back to their parents for delivery.

Nusserwanjis story was no different. In the first decade of his life he was married off to a petite little girl with a name that bespoke a lifetime of experience: Jeevanbai. Mrs Nusserwanji was taken home promptly after marriagein fact, the same eveningand stayed home for nearly ten years before rejoining her spouse. A year after she returned, her husband turned seventeen and she gave birth to their first child, Jamset, on 3 March 1839.

This child, Jamsetji Nusserwanji Tata, would become the grand old man, the Bhishma Pitamah, of Indian industry, laying the foundations of a global business empire. Though his star would take him high, Jamsetji Tata stayed true to his roots, following in the footsteps of his father.

Young Nusserwanji knew early on that he did not want to follow family tradition and become a priest. Driven by a deep passion to do something of his own, he knew his destiny lay beyond Navsari. No one else in the village had ever felt that way, not strongly enough to leave Navsari anyway. For its residents, the village was their world. Nusserwanji was the first member of his family to leave.