Contents

For Caitlin, Matt and Nick Spille

FOREWORD

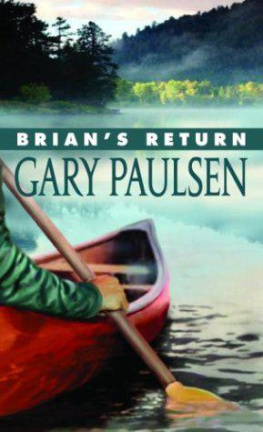

This book was written for all those readers of Hatchet and The River who wrote (I received as many as two hundred letters a day) to tell me they felt Brian Robesons story was left unfinished by his early rescue before, they said, it became really hard going. They asked: What would happen if Brian hadnt been rescued, if he had had to survive in the winter? Since my life has been one of survival in winterrunning two Iditarods, hunting and trapping as a boy and young manthe challenge became interesting, and so I researched and wrote Brians Winter , showing what could and perhaps would have happened had Brian not been rescued.

For the purpose of this story it is necessary to shift the idea left by Hatchet and suppose that although Brian did retrieve the survival pack from the plane, he did not trigger a radio signal and did not get rescued. Other than that I hope I have remained true to the story in Hatchet and that this book will answer the question of Brians winter survival.

It is important to note, however, that his previous knowledge was vitalhe had to know summer survival to attempt living in winter. Had he been dropped in the winter with no previous knowledge of hunting, surviving, no education gained in the school of hard knocks during the summer, Brian probably would have died no matter what his luck or abilities.

Part One

FALL

Chapter

ONE

Fall came on with a softness, so that Brian didnt realize what was in storea hard-spined north woods winteruntil it was nearly too late.

He had never thought he would be here this long. After the plane crash that marooned him in the wilderness he had lived day by day for fifty-four days, until he had found the survival pack in the plane. Then another thirty-five days through the northern summer, somehow living the same day-to-day pattern he had started just after the crash.

To be sure he was very busy. The emergency pack on the plane had given him a gun with fifty shellsa survival .22 riflea hunting knife with a compass in the handle, cooking pots and pans, a fork, spoon and knife, matches, two butane lighters, a sleeping bag and foam pad, a first-aid kit with scissors, a cap that said CESSNA , fishing line, lures, hooks and sinkers, and several packets of freeze-dried food. He tried to ration the food out but found it impossible, and within two weeks he had eaten it all, even the package of dried prunessomething hed hated in his old life. They tasted like candy and were so good he ate the whole package in one sitting. The results were nearly as bad as when hed glutted on the gut cherries when he first landed. His stomach tied in a knot and he spent more than an hour at his latrine hole.

In truth he felt relieved when the food was gone. It had softened him, made him want more and more, and he could tell that he was moving mentally away from the woods, his situation. He started to think in terms of the city again, of hamburgers and malts, and his dreams changed.

In the days, weeks and months since the plane had crashed he had dreamed many times. At first all the dreams had been of foodfood he had eaten, food he wished he had eaten and food he wanted to eat. But as time progressed the food dreams seemed to phase out and he dreamed of other thingsof friends, of his parents (always of their worry, how they wanted to see him; sometimes that they were back together) and more and more of girls. As with food he dreamed of girls he knew, girls he wished he had known and girls he wanted to know.

But with the supplies from the plane his dreams changed back to food and when it was gonein what seemed a very short timea kind of wanting hunger returned that he had not felt since the first week. For a week or two he was in torment, never satisfied; even when he had plenty of fish and rabbit or foolbird to eat he thought of the things he didnt have. It somehow was never enough and he seemed to be angry all the time, so angry that he wasted a whole day just slamming things around and swearing at his luck.

When it finally endedwore away, was more like ithe felt a great sense of relief. It was as if somebody he didnt like had been visiting and had finally gone. It was then that he first really noted the cold.

Almost a whiff, something he could smell. He was hunting with the rifle when he sensed the change. He had awakened early, just before first light, and had decided to spend the entire day hunting and get maybe two or three foolbirds. He blew on the coals from the fire the night before until they glowed red, added some bits of dry grass, which burst into flame at once, and heated water in one of the aluminum pots that had come in the planes survival pack.

Coffee, he said, sipping the hot water. Not that hed ever liked coffee, but something about having a hot liquid in the morning made the day easier to startgave him time to think, plan his morning. As he sipped, the sun came up over the lake and for the hundredth time he noted how beautiful it wasmist rising, the new sun shining like gold.

He banked the fire carefully with dirt to keep the coals hot for later, picked up the rifle and moved into the woods.

He was, instantly, hunting.

All sounds, any movement went into him, filled his eyes, ears, mind so that he became part of it, and it was then that he noted the change.

A new coolness, a touch, a soft kiss on his cheek. It was the same air, the same sun, the same morning, but it was different, so changed that he stopped and raised his hand to his cheek and touched where the coolness had brushed him.

Why is it different? he whispered. What smell

But it wasnt a smell so much as a feeling, a newness in the air, a chill. There and gone, a brush of new-cool air on his cheek, and he should have known what it meant but just then he saw a rabbit and raised the little rifle, pulled the trigger and heard only a click. He recocked the bolt, made certain there was a cartridge in the chamber and aimed againthe rabbit had remained sitting all this timeand pulled the trigger once more. Click .

He cleared the barrel and turned the rifle up to the dawn light. At first he couldnt see anything different. He had come to know the rifle well. Although he still didnt like it muchthe noise of the small gun seemed terribly out of place and scared game awayhe had to admit it made the shooting of game easier, quicker. He had a limited number of shells and realized they would not last forever, but he still had come to depend on the rifle. Finally, as he pulled the bolt back to get the light down in the action, he saw it.

The firing pina raised part of the boltwas broken cleanly away. Worse, it could not be repaired without special tools, which he did not have. That made the rifle worthless, at least as far as being a gun was concerned, and he swore and started back to the camp to get his bow and arrows and in the movement of things completely ignored the warning nature had put on his cheek just before he tried to shoot the rabbit.

In camp he set the rifle asideit might have some use later as a tooland picked up the bow.

He had come to depend too much on the rifle and for a moment the bow and handful of arrows felt unfamiliar to his hands. Before he was away from the camp he stopped and shot several times into a dirt hummock. The first shot went wide by two feet and he shook his head.

Focus, he thought, bring it back.

On the second shot he looked at the target, into the target, drew and held it for half a secondfocusing all the while on the dirt humpand when he released the arrow with a soft thrum he almost didnt need to watch it fly into the center of the lump. He knew where the arrow would go, knew before he released it, knew almost before he drew it back.

Next page