Many of the designations used by manufacturers and sellers to distinguish their products are claimed as trademarks. Where those designations appear in this book and Da Capo Press was aware of a trademark claim, those designations have been printed with initial capital letters.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher. Printed in the United States of America.

Da Capo Press books are available at special discounts for bulk purchases in the U.S. by corporations, institutions, and other organizations. For more information, please contact the Special Markets Department at the Perseus Books Group, 11 Cambridge Center, Cambridge, MA 02142, or call (800) 255-1514 or (617) 252-5298, or e-mail .

PROLOGUE

The Flip

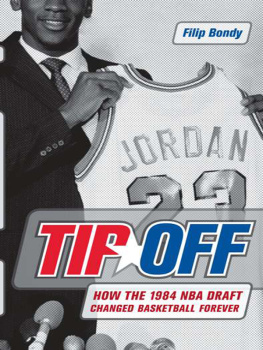

O n the late morning of Tuesday, May 22, 1984, two opposing groups of thoroughly superstitious team officials converged on the NBA offices in Manhattan to pray for good fortune, to flip a coin, and to redraw the leagues burgeoning road map for decades to come. They all hoped to win the big prize in the Olajuwon lottery, though there were certainly some intriguing alternatives. College basketball in 1984 was chock full of individual genius, a bushel of seasoned, polished upperclassmen eager to impact the league in their rookie professional season. Consider some of the players who had just been showcased in the forty-eight-team NCAA tournament, whetting appetites for NBA fans: Patrick Ewing, playing center, helped Georgetown capture the title. And while Ewing decided to remain a Hoya for another year, Hakeem Olajuwon (he was still Akeem back then, at least to the public) chose to leave school early and declare for the draft. He had played fearlessly in that same tournament for the University of Houston, leading the Cougars to the final. Sam Bowie and Mel Turpin, two talented big men, reached the Final Four with Kentucky. Michael Jordan and Sam Perkins at North Carolina were brilliant at times but lost unexpectedly early on to Indiana. And while Auburn could not quite measure up to these other top basketball schools, its star, Charles Barkley, was a hurricane force out of the Southeast Conference.

These players, and their arrival at this special moment in time, would mean the birth of a new National Basketball Association, the modern NBA. The league that was waiting anxiously for this wave of saviors was very different from the one that exists today, at a crossroads in so many ways. The NBA in 1984 had only recently turned the corner from its darkest days, from the budget deficits affecting seventeen of twenty-three franchises and the kind of rampant substance abuse that was coming to light through the well-publicized plights of Micheal Ray Richardson and Quintin Dailey. In 1983, the NBA and its Players Association adopted their first drug program, aimed particularly at those societal scourges: cocaine and heroin. A system of testing, based on reasonable cause for suspicion, was put into place, and a series of penalties was introduced in three stepsa period of rehabilitation, without loss of pay, for the first voluntary admission of drug use; a suspension without salary during the rehab period for the second violation; and a permanent league ban for a third violation. A relatively rumpled league attorney, David Stern, accepted the reins from a well-connected, hands-off politician, Lawrence OBrien, who had been more at ease as campaign manager of John F. Kennedy than as keeper of the flame for Bob Cousy and Bill Russell. Stern inherited a stagnant business from OBrien, and the new commissioner envisioned an aggressive marketing strategy to turn the league around with assistance from salary controls.

The transition at the top heralded the start of a hands-on regulation era. Earlier, as aggressive point men for the league, Stern and his lieutenant, future NHL commissioner Gary Bettman, won a salary cap in 1983 during collective bargaining negotiations with the players union. The nascent NBA once had a cap in the 1940s but abandoned it after just one season. Groundbreaking for professional sports, the new system would go into effect for the 198485 season, basing the cap on 55 percent of the leagues total revenues. The maximum combined player payroll would be set at $3.6 million for each team. Twenty-one years later, for the 200506 season, the cap number was $49.5 million, and many franchises were well over that number because of rule exceptions. The average salary of players in 1984 was $340,000 and would grow to $4.28 million within two decades.

The things we worried about then... , Stern said, looking back. Most of all, the league fretted about getting its product on television. No network wanted any part of the NBA in prime time, so Stern found himself scheduling playoff games on back-to-back Saturday and Sunday afternoons, just so they would be broadcast live. Even later, the year the NFL was on strike [1987], CBS would rather put on a St. Johns Yugoslavia game, Stern said. They wanted $50,000 from us to get our games on. We were begging them to get on.

Ironically, the NBA was in its competitive and artistic heyday at this time. The playoffs that spring of 1984 produced incredible basketball, dramatic matchups that ended in a sublime, seven-game victory by the Boston Celtics over the Los Angeles Lakers in the finals. Larry Bird and Magic Johnson were incomparable bicoastal rivals. And yet these stars were still not transcendent in a global marketing sense. They were most famous for their passes, for their championships, not for their dunks or for their shoes or for their off-court trash talk. Playoff games finally were being shown live, instead of on tape, but networks were just beginning to bid for rights.

So this would be a brave new world, and the class of rookies would be its founding fathers. Fresh, exciting dynamics were suddenly in place. Stern was leading the charge toward competitive parity with his crusade, the salary cap. Younger players were leaving college before their graduation, offering yet another layer of suspense to the draft: Will he stay, or will he go? As the stakes grew, players looked to maximize their marketing power. Family friends and lawyers no longer afforded adequate representation. Super agents with big firms and impressive client lists would soon determine the very composition of the league and its teams. And then there were the sneakers, the fast food chains, the soft drinks. Endorsements and television money were about to change all the rules, forever.

The league in 1984 was in its last throes of a stubborn plutocracy, dominated by a powerful ruling triumvirate: the Boston Celtics, the Los Angeles Lakers, and the aging Philadelphia 76ers. The rosters of too many other teams were paper-thin in marketable stars. The coin flip to determine the first draft pick on May 22 represented a chance for either the Houston Rockets or the Portland Trail Blazers to change all that, to transform the trio of elite teams into a quartet. Olajuwon wasnt a particularly glamorous figure. He wasnt even American. But the Nigerian star figured to have an immediate impact. He was big, smart, and agile. He owned surprising court savvy despite his inexperience. Title teams were built around such centers, guys like Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Robert Parish. Olajuwon looked like a franchise player who figured to win a championship or two.