Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

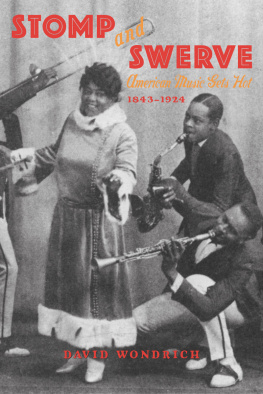

Wondrich, David.

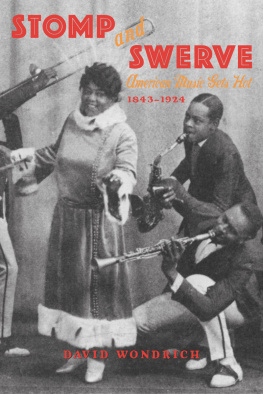

Stomp and swerve : American music gets hot,

18431924 / by David Wondrich. 1st ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ), discography, and index.

ISBN 1-55652-496-X

1. Popular musicUnited StatesHistory and criticism. 2. African AmericansMusicHistory and criticism. 3. JazzHistory and criticism. I. Title.

ML3477.W69 2003

781.640973dc21

2003004480

Cover photo: Mamie Smith and Her Jazz Hounds,

courtesy of the Frank Driggs collection

Cover and interior design: Laura Lindgren

2003 by David Wondrich

All rights reserved

First Edition

Published by A Cappella Books,

An imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 1-55652-496-X

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

For Karen

Contents

Preface

The eighty-odd years between 1843, when a new, indigenous style of music-making first came to the attention of the American general public, and the early 1920s, when its full spectrumblack and white, urban and rural, sophisticated as silk lingerie and crude as cotton overallsfinally made it on record for all to hear, are the caveman period of American music. An age of firelit darkness, sundered by the screech of badly tuned fiddles. For the eighty years since, on the other hand, the story is a familiar one. The key players, in this age of Britney Spears, might not all be the household names they once were, but they suffer no lack of recognition; all their records are in print and theres no shortage of books about em. Louis Armstrong, Bessie Smith, Robert Johnson, Jimmie Rogers, Bob Wills, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Billie Holiday, Benny Goodman, Charlie Parker, Hank Williams, Elvis Presley, Little Richard, Jerry Lee Lewis, so on and so forth. Benchmark names. Names that you cant ignore in any serious discussion of American music.

Against those monumental names, those early decades have only three to offer: Scott Joplin, Stephen Foster, and John Philip Sousa (although Sousas often not taken as seriously as he deserves). There are plenty of others who should be there, but arent. This book is an essay, not a formal, comprehensive history; an attempt to bring the missing names into the conversation; to treat the music made by fiddling minstrels and brass bands, ragtime piano professors and concert banjoists, singers of Coon songs (well get to that in a minute), ragtime dance orchestras, vocal quartets, novelty drummers, and Broadway cakewalkers with the same honesty, sympathy, and passion were accustomed to find in writing about the music that followed them.

The roots of this book reach back to the fall of 1977, when I was in eleventh grade, living with my folks in Port Washington, out on Long Island. One afternoon, a friend and I took the Long Island Railroad into Manhattan to buy posters or some such thing. On the way home, we stopped at the Sam Goodys record store in Penn Station, and I bought Never Mind the Bollocks, Heres the Sex Pistols. Usually, I listened to the Allman Brothers, the Grateful Dead, that sort of thing, but an impulse came over me and I obeyed it. Later, when I played the record, I thought it was... intense. More intense than anything. Ever. (I was sixteen.)

A few days later, on my way home from school I stopped in at the Neergard Pharmacy on Main Street, one of those mom-and-pop affairs that had a small record departmenttop-twenty new releases and a rack or two of $2.99 cutouts. Leafing through the cutouts, I came across a Columbia LP called King of the Delta Blues Singers, Vol. II by Robert Johnson. Id never heard of Robert Johnson, but it looked like a goofold and weird and good for springing on my friends, tormenting them with. Besides, for $2.99 plus tax, I could be a sport. I didnt get around to playing it for a couple of days.

When I did, I learned a lesson. Its an old one; as Anthony Cooper, Earl of Shaftesbury, formulated it in 1710, those who are ignorant of history and the evolution of taste are apt at every turn to make the present age their standard, and imagine nothing so barbarous or savage but what is contrary to the manners of their own time. Of course, in this case it was me imagining nothing so barbarous or savage as the music that was a product of the manners of my own time, but the principles the same. I had been making the present my standard, and I was wrong. The recordings on that LP were forty years old when I first listened to them, and yet they were just as intense, just as punky, wild, weird, and modern, as anything Johnny Rotten and his mates were churning out.

I know that by comparing Johnny Rotten to Robert Johnson I risk completely alienating any blues fanatics who may be reading this; I can only beg your patience. In fact, here I should probably assure those among you who find rock n roll distasteful that this is not a book about rock n roll, or, for that matter, soul music, funk, or rap. This is a book about the music of the past; old music. But it is a book that treats that music as if it were made not by the solemn, still faces in old black-and-white photographs, but by young (mostly) men and women, people with the same hormones, the same nerves, the same needs and desires and capacities for fulfilling them that drove Elvis Presley and Jerry Lee Lewis, Aretha Franklin and James Brown, Jimi Hendrix and, yes, even Ozzy Osbourne. This means that while discussing ragtime and early jazz, minstrel shows and brass bands and all the other foundational manifestations of hot music in America, I shall be drawing the occasional analogy from the vernacular music of the present (or at least the recent past). Since these days the odds are pretty good that even the most hardened bluegrass fiend, blues scholar, jazzbo, or ragtimer grew up listening to the same crap as the rest of us, I think it will do most no harm. Anyway, the line of influence from antebellum minstrel Daniel Decatur Emmett to Kid Rock, from Bert Williams, the first black man to appear in a Broadway show, to Outkast, is unbroken, though rarely acknowledged.

There are two reasons why this tradition has so often been ignored. One is technical: the kind of energetic, informal music were dealing with here has always been difficult to get down on paper. Transcriptions miss the vigor and charm of the performers, without which this music is nothing, while written descriptionshow can you really write about music? Its like writing about the taste of malt whiskey. To really do justice to it, you need to preserve the performance itself. You need records. Unfortunately, for the first four decades of our period, there were none. Then came December 7, 1877a day that shall live in harmonywhen a certain John Kruesi, one of Thomas Edisons mechanics, put the finishing touches on the masters design for a device to pluck vibrations out of the air and imprison them in the narrow track a needle leaves on a rotating cylinder of tinfoil. By the early 1890s, this simple technology was mature enough to support an industry. By 1910, thousands upon thousands of different records had been made of all kinds. Many were of classical music, opera, parlor songs, that sort of thing. Others, though, were in the direct ancestral line of Robert Johnson and the Sex Pistols. Not that youd know that from the amount of attention they receive from historians of popular music. True, theyre kind of hard to listen to scratchy and often dimly recorded. Thats no excuse, though, for the serious listener; those records were cut on the same equipment that Carusos were, and folks write about him plenty.

Next page