Of Men and Mountains

by

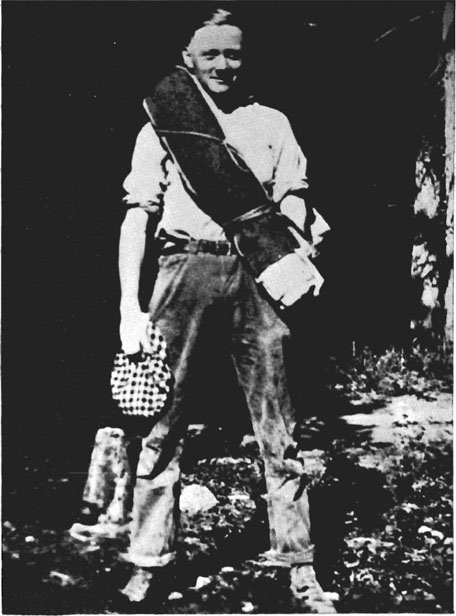

WILLIAM O. DOUGLAS

1914

Contents

Foreword

THE mountains of the Pacific Northwest are tangled, wild, remote, and high. They have the roar of torrents and avalanches in their throats.

Rock cliffs such as Kloochman rise as straight in the air as the Washington Monument and two or three times as high. Snow-capped peaks with aprons of eternal glaciers command the skylinegiant sentinels 11,000, 12,000, 14,000 feet high, such as Hood, Adams, and Rainier.

There are no slow-moving, sluggish rivers in these mountains. The streams run clear, cold, and fast.

There are remote valleys and canyons where man has never been. The meadows and lakes are not placid, idyllic spots. The sternness of the mountains has been imparted to them.

There are cougar to scout the camp at night. Deer and elk bed down in stands of mountain ash, snowbrush, and mountain-mahogany. Bears patrol streams looking for salmon. Mountain goat work their way along cliffs at dizzy heights, searching for moss and lichens.

Trails may climb 4,000 feet or more in two miles. In twenty miles of travel one may gain, then lose, then gain and lose once more, several thousand feet of elevation.

The blights of forest fires, overgrazing, avalanches, and excessive lumbering have touched parts of this vast domain. But civilization has left the total scene in strange degree alone.

These tangled masses of thickets, ridges, cliffs, and peaks are a vast wilderness area. Here man can find deep solitude, and under conditions of grandeur that are startling he can come to know both himself and God.

This book is about such discoveries. In this case they are discoveries that I made; so in a limited sense the book is autobiographical.

I learned early that the richness of life is found in adventure. Adventure calls on all the faculties of mind and spirit. It develops self-reliance and independence. Life then teems with excitement. But man is not ready for adventure unless he is rid of fear. For fear confines him and limits his scope. He stays tethered by strings of doubt and indecision and has only a small and narrow world to explore.

This book may help others to use the mountains to prepare for adventure.

Theyif they are among the uninitiatedmay be inspired to search out the high alpine basins and fragile flowers that flourish there. They may come to know the exhilaration of wind blowing through them on rocky pinnacles. They may recognize the music of the conifers when it comes both in whispered melodies and in the fullness of the wind instruments. They may discover the glory of a blade of grass and find their own relationship to the universe in the song of the willow thrush at dusk. They may learn to worship God where pointed spires of balsam fir turn a mountain meadow into a cathedral.

Discovery is adventure. There is an eagerness, touched at times with tenseness, as man moves ahead into the unknown. Walking the wilderness is indeed like living. The horizon drops away, bringing new sights, sounds, and smells from the earth. When one moves through the forests, his sense of discovery is quickened. Man is back in the environment from which he emerged to build factories, churches, and schools. He is primitive again, matching his wits against the earth and sky. He is free of the restraints of society and free of its safeguards too.

Boys, perhaps more deeply than men, know this experience. Eleanor Chaffee has expressed that concept poignantly:

Who but a boy would wander into the night

Against the sensible advice of those much older,

Where silent shadows cut the moons thin light

And only maples lean to touch his shoulder?

What does he hope to find, what fever stirs

His blood and guides his feet to walk alone?

He will return, his sweater stuck with burrs

And in his hand a useless, shapeless stone,

But something in his face, secret, withdrawn

Will go with him upstairs, and to his sleep.

He is as furtive now as a young wild fawn:

His eyes are darker now, and large and deep.

Who but a boy can find such subtle magic

In the world his elders find so grave, so tragic?

These pages contain what I, as a boy, saw, felt, smelled, tasted, and heard in the mountains of the Pacific Northwest. At least the record I have written is as accurate as memory permits. Those who walked the trails with me as a boyBradley Emery, Douglas Corpron, Elon Gilbert, Arthur F. Douglasare happily all alive. So they have let me draw upon their memories too and make many demands on their time and energies in the preparation of these chronicles.

The boy makes a deep imprint on the man. My young experiences in the high Cascades have placed the heavy mark of the mountains on me. And so the excitement that alpine meadows and high peaks created in me comes flooding back to make each adult trip an adventure. As the years have passed I have found in these experiences a spiritual significance that I could not fully sense before. That is why the book, though about a boy, is in total effect an adult version.

Many have assisted me in this task. It was the quiet encouragement of Phil Parrish and Stanley and Nancy Young that led me to finish the book. And it was the hard-edged mind of Phil Parrish that helped me put the text in final form. Many others have given me aid along the way. Lyle F. Watts, Walt Dutton, Lloyd Swift, H. J. Andrews, Fred Kennedy, Joseph F. Pechanec, Glenn Mitchell, Charles Rector, Chester Bennett, and Wade Hall of the Forest Service; Stanley Jewett, Elmo Adams, and John Scharff of the Fish and Wild Life Service; Ira Gabrielson, formerly chief of that servicethese men have ridden the trails with me and helped me see and understand the beauties of the mountains. They also assisted me in analyzing a mass of scientific material bearing on the conservation of wildlife and water and topsoil that my mountain expeditions produced. That material was originally intended for this book; but in view of its nature and volume it has been saved for later publication. William A. Dayton, Donald C. Peattie, and Melvin Burke have been my patient instructors in botany. None could ask for better ones. Dean Guie of Yakima, Palmer Hoyt of Denver, Saul Haas of Seattle, Richard L. Neuberger of Portland, Robert W. Sawyer of Bend, Alba Show-away of Parker, Mrs. George W. McCredy of Bickleton, John P. Buwalda of Pasadena, and all those who walk through these pages, particularly Jack Nelson, Roy Schaeffer, and the late Clarence Truitt granted me assistance along the way. Walt Dutton, Josephine Waggaman, James Powell, and Rudolph A. Wendelin produced the maps that appear as end papers in this volume. Edith Allen and Gladys Giese carried the burden of the typing.

I must add a special word about two of the characters. Elon Gilbert almost gave. his life for the book. When field studies were being made in 1948, he was in a truck loaded with horses that rolled into a canyon on the eastern slopes of Darling Mountain. It was he who scaled the cliffs on Goat Rocks to drop a rope to me that I might climb in safety. He also carried much of the burden of the field research that went into this work. We shared together, as boys and men, the adventure of this story.

Doug Corpron was one of the doctors who attended me after the horseback accident in October, 1949 that almost proved fatal. During the first few days in the hospital it seemed that whenever I opened my eyesnight or dayDoug was by my bedside. Then one day he stood over me with a grin on his face. There was a note of bravado in his voice as he said, That was another tough climb we had together. But we made it, just as we once conquered Kloochman.