T HERE WAS THIS disease that the clacksmen got.

It was like the illness known as calenture, which sailors experienced when, after having been becalmed for weeks under a pitiless sun, they suddenly believed that the ship was surrounded by green fieldsand stepped overboard.

Sometimes the clacksmen thought they could fly.

There was about eight miles between the big semaphore towers, and when you were at the top you were maybe a hundred and fifty feet above the plains. Work up there too long without a hat on, they said, and the tower you were on got taller, and the nearest tower got closer, and maybe you thought you could jump from one to another, or ride on the invisible messages sleeting between the towers, or perhaps you thought that you were a message. Perhaps, as some said, all this was nothing more than a disturbance in the brain caused by the wind in the rigging. No one knew for sure. People who step onto the air one hundred and fifty feet above the ground seldom have much to discuss afterwards.

The tower shifted gently in the wind, but that was okay. There were lots of new designs in this tower. It stored the wind to power its mechanisms, it bent rather than broke, it acted more like a tree than a fortress. You could build most of it on the ground and raise it into place in an hour. It was a thing of grace and beauty. And it could send messages up to four times faster than the old towers, thanks to the new shutter system and the colored lights.

The young man climbed swiftly to the very top of the tower. For most of the way he was in clinging, gray morning mist, and then he was rising through glorious sunlight, the mist spreading below him, all the way to the horizon, like a sea.

He paid the view no attention. Hed never dreamed of flying. He dreamed of mechanisms, of making things work better than theyd ever done before.

Right now he wanted to find out what was making the new shutter array stick again . He oiled the sliders, checked the tension on the wires, and then swung himself out over fresh air to check the shutters themselves. It wasnt what you were supposed to do, but every linesman knew it was the only way to get things done. Anyway, it was perfectly safe if you

There was a clink. He looked back and saw the snap-hook of his safety rope lying on the walkway, saw the shadow, felt the terrible pain in his fingers, heard the scream and dropped

like an anchor.

In which our hero experiences Hope,

the greatest gift * The bacon sandwich of regret

* Somber reflections on capital punishment

from the hangman * Famous last words * Our hero dies

* Angels, conversations about * Inadvisability of

misplaced offers regarding broomsticks * An unexpected ride

* A world free of honest men * A man on the hop

* There is always a choice

T HEY SAY THAT the prospect of being hanged in the morning concentrates a mans mind wonderfully; unfortunately, what the mind inevitably concentrates on is that, in the morning, it will be in a body that is going to be hanged.

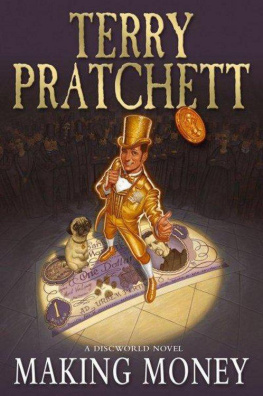

The man going to be hanged had been named Moist von Lipwig by doting if unwise parents, but he was not going to embarrass the name, insofar as that was still possible, by being hung under it. To the world in general, and particularly on that bit of it known as the death warrant, he was Alfred Spangler.

And he took a more positive approach to the situation and had concentrated his mind on the prospect of not being hanged in the morning, and, most particularly, on the prospect of removing all the crumbling mortar from around a stone in his cell wall with a spoon. So far the work had taken him five weeks and reduced the spoon to something like a nail file. Fortunately, no one ever came to change the bedding here, or else they would have discovered the worlds heaviest mattress.

It was a large and heavy stone that was currently the object of his attentions, and, at some point, a huge staple had been hammered into it as an anchor for manacles.

Moist sat down facing the wall, gripped the iron ring in both hands, braced his legs against the stones on either side, and heaved.

His shoulders caught fire, and a red mist filled his vision, but the block slid out with a faint and inappropriate tinkling noise. Moist managed to ease it away from the hole and peered inside.

At the far end was another block, and the mortar around it looked suspiciously strong and fresh.

Just in front of it was a new spoon. It was shiny.

As he studied it, he heard the clapping behind him. He turned his head, tendons twanging a little riff of agony, and saw several of the wardens watching him through the bars.

Well done , Mr. Spangler! said one of them. Ron here owes me five dollars! I told him you were a sticker! Hes a sticker, I said!

You set this up, did you, Mr. Wilkinson? said Moist weakly, watching the glint of light on the spoon.

Oh, not us, sir. Lord Vetinaris orders. He insists that all condemned prisoners should be offered the prospect of freedom.

Freedom? But theres a damn great stone through there!

Yes, there is that, sir, yes, there is that, said the warden. Its only the prospect , you see. Not actual free freedom as such. Hah, thatd be a bit daft, eh?

I suppose so, yes, said Moist. He didnt say you bastards. The wardens had treated him quite civilly these past six weeks, and he made a point of getting on with people. He was very, very good at it. People skills were part of his stock-in-trade; they were nearly the whole of it.

Besides, these people had big sticks. So, speaking carefully, he added: Some people might consider this cruel, Mr. Wilkinson.

Yes, sir, we asked him about that, sir, but he said no, it wasnt. He said it providedhis forehead wrinkledocc-you-pay-shun-all ther-rap-py, healthy exercise, prevented moping, and offered that greatest of all treasures, which is Hope, sir.

Hope, muttered Moist glumly.

Not upset, are you, sir?

Upset? Why should I be upset, Mr. Wilkinson?

Only the last bloke we had in this cell, he managed to get down that drain, sir. Very small man. Very agile.

Moist looked at the little grid in the floor. Hed dismissed it out of hand.