Copyright 1993, 2004 by Macon Shibut All rights reserved.

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 2004, is an unabridged republication of the work originally published in 1993 by Caissa Editions, Yorklyn, Delaware. An addendum to this book, printed by the original publisher, has been included in this edition. A list of errata has been specially prepared for this edition by the author.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Shibut, Macon.

Paul Morphy and the evolution of chess theory / Macon Shibut. p. cm.

Includes indexes.

9780486149875

1. Morphy, Paul Charles, 1837-1884. 2. ChessCollections of games. I. Title.

GV1439.M7S45 2004

2003070112

Manufactured in the United States of America

Dover Publications, Inc., 31 East 2nd Street, Mineola, N.Y 11501

Table of Contents

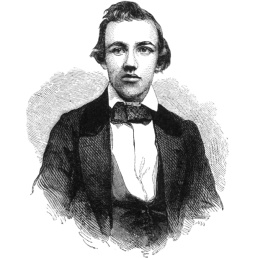

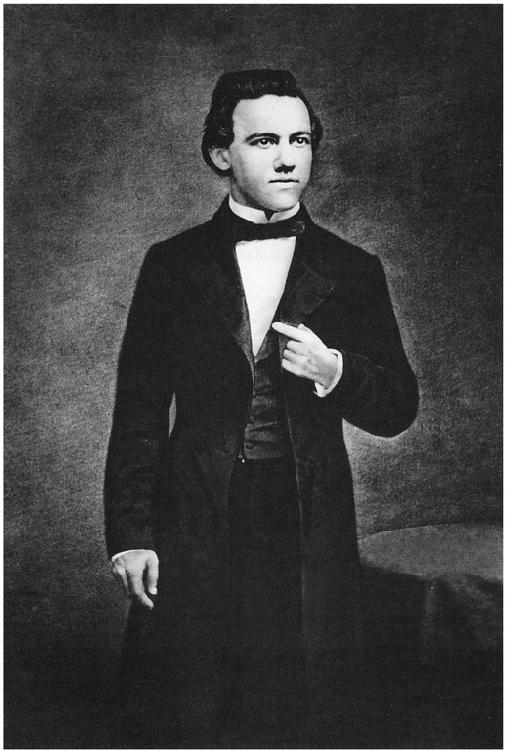

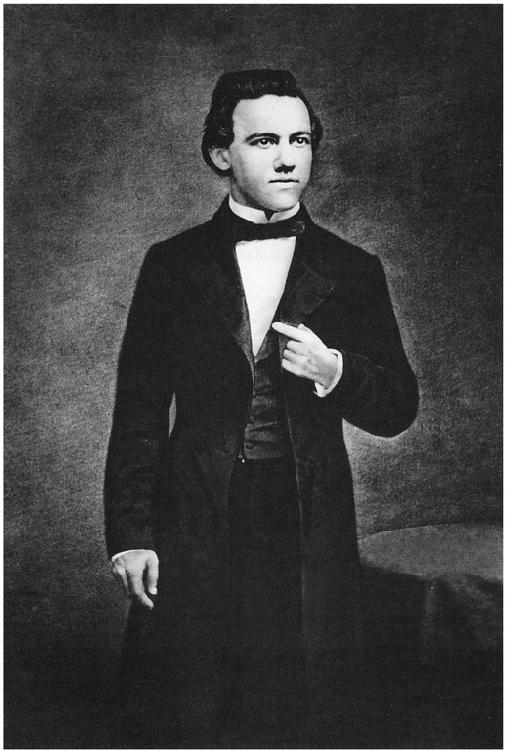

Matthew Brady photo, New York, 1859

Introduction

Paul Morphy needs little introduction. This opening sentence from the Batsford reprint of Lowenthals classic Morphys Games of Chess fairly reflects a popular modem attitude. Morphy was, after all, the most famous chess player ever. Certainly the outline of his story is familiar to all chess players: The Pride and Sorrow of Chess; the great natural player who came from nowhere to conquer his countrymen and later to vanquish the greatest masters of Europe. Too soon afterwards he withdrew from competition, failed as a lawyer, failed in private life generally suffered delusions, died young. But we celebrate the queen sacrifice by which Morphy pried open Louis Paulsens king position. We remember how he sacrificed practically everything to mate the Duke of Brunswick, between acts at a Paris opera. What more is there to know?

Indeed I thought I needed no introduction to Paul Morphy. But when I finally got around to a more comprehensive study of his play, I was surprised to discover how many of the games that I had not been shown previously were, in their own manner, more interesting than the usual anthology pieces. Morphys brilliancies, for all their beauty and instructional value, lack something in the way of drama and struggle. Theyre just a bit too elegant, too fine. Its hard to imagine them as games actually played in the atmosphere of hope and fear that animates over-the-board chess. On the other hand, if the unknown Morphy games lack that glittering final combination needed to ensure their immortality, its all the more fascinating to see Morphys familiar combinative vision straining against the rich uncertainty of practical play.

I offer this book as a guide through Paul Morphys chess - not the greatest games tourist route, but also the back streets where real struggles were decided. (Which is not to say we wont glimpse some historical landmarks too!) Part I reflects upon some popular preconceptions and prejudices concerning the pride and sorrow of chess, where they came from, and the very different impressions that can arise from examining Paul Morphys games first hand. Part II presents every available Morphy game, collected together in an English language volume for the first time. (Throughout the book, braces {} indicate a reference to a game score from Part II.) Finally, for added historical perspective, Part III makes available some thoughts on Paul Morphy by two of chesss greatest champions, Wilhelm Steinitz and Alexander Alekhine.

I am indebted to Dale Brandreth for access to this latter material and the various illustrations, all of which appear with his permission. More generally, I am indebted to many analysts and authors whose work I consulted. Most are acknowledged in the text when I quote a particular variation or evaluation. Three sources deserve special mention here, each of them having been essential to the creation of Paul Morphy and the Evolution of Chess Theory . If this volume is found to contribute materially to the body of Morphy literature, that will be largely thanks to the foundation they provided:

Morphys Games of Chess . By J. J. Lowenthal. London, 1860.

Paul Morphy . By Geza Maroczy. Leipzig,1909.

Morphys Games of Chess . By Philip W. Sergeant. 3rd ed., London, 1919.

My trusty Olms reprint of Maroczys book is the source for the bulk of Part IIs game scores. However, I also incorporated many corrections and additions that have surfaced during the eighty-plus years since Maroczy first published. I found these mainly in books by Philip Sergeant, David Lawson, and some scattered magazine articles by Andrew Soltis (in which he too acknowledges Lawson as a source).

Macon Shibut

December, 1992

PART I - Analysis

Paul Morphy and the Play of Our Time

Paul Morphys masterpieces are ubiquitous in chess literature. Couple that with the brevity of his career, and its easy for students to imagine they already know every Morphy game. In truth, most chess players probably have seen only a few dozen - but these theyve seen a hundred times apiece.

Too often a champions legacy derives from a minuscule, unrepresentative sample of his total product. In Morphys case especially, the public has been conditioned to believe his games were all brilliancies and none of his contemporaries could make him break a sweat. This impression began to arise even while Morphy was still active. It was well-established by the time he died in 1884, at just forty-seven years of age. One year later, Wilhelm Steinitz attempted to impart some perspective on the Morphy Myth with his essay, Paul Morphy and the Play of His Time. Writing in his International Chess Magazine , Steinitzargued that,

By mixing up Morphys blindfold, off-hand, and odds games with those of his serious encounters against strong masters, popular prejudice has [wrongly] credited Morphy with the faculty of creating positions against his strongest opponents, in which brilliant sacrifices formed a distinct feature...

But a popular prejudice, once entrenched, is not easily displaced. Steinitzs essay attracted notice and controversy in its day, but few modem players have had an opportunity to read it. Meanwhile, everyone has seen Morphys famous game with the Duke of Brunswick! Thus a handful of Morphys light workouts, against mostly weak amateurs, have come to be esteemed as the standard of 19th century master chess.

There are over four hundred recorded Morphy games. In setting out to explore them, a modem player will want to treat each move and each position with an open mind, to play the board, not the man. In this regard, analysis of older games demands a special psychological discipline. The truth is that we do possess hindsight knowledge, not only regarding a particular game, but the players whole careers and the age in which they played. Like it or not, this knowledge tends to intrude into the domain of objective analysis.

For example, old fashioned openings invoke a prejudice in modem players. The resulting middlegame structures look unsophisticated, and it becomes all too easy to substitute historical perspective (he played thus because they didnt understand pawn weaknesses back then...) for hard analysis.

Knowing the outcome of a game can likewise distort our assessment of its individual moves. The losers mistakes will be mechanically identified and condemned; the winners exploitation will be accepted uncritically. This danger exists even when dealing with modem games. The tendency is exacerbated with a game from another era, all the more so if a near-mythical figure like Morphy is involved. Annotators who want to educate or entertain are not interested in tearing apart an instructive Morphy combination. Rather, they want to find characteristic errors in the opponents play, and they want the heros consequent victory to seem a matter of course (and the more elegantly achieved, the better).

Next page