BLOOD & FIRE

William and Catherine Booth and Their Salvation Army

Roy Hattersley

Roy Hattersley is a politician-turned-writer. He was elected to Parliament in 1964, and served in each of Harold Wilsons governments and in Jim Callaghan's Cabinet. In 1983 he became deputy leader of the Labour Party. He has written 'Endpiece', his Guardian column, for seventeen years, and before that was a columnist for Punch and the Listener. For two years he was television critic of the Daily Express. As well as contributing to the Daily Mail, Observer and The Times he has written fourteen books - including the much-acclaimed Who Goes Home?and Fifty Years On, the classic A Yorkshire Boyhood and three novels: The Makers Mark, In That Quiet Earth and Skylarks Song. He has been Visiting Fellow of Harvard's Institute of Politics and of Nuffield College, Oxford. He is a Visiting Professor of Politics at Sheffield University.

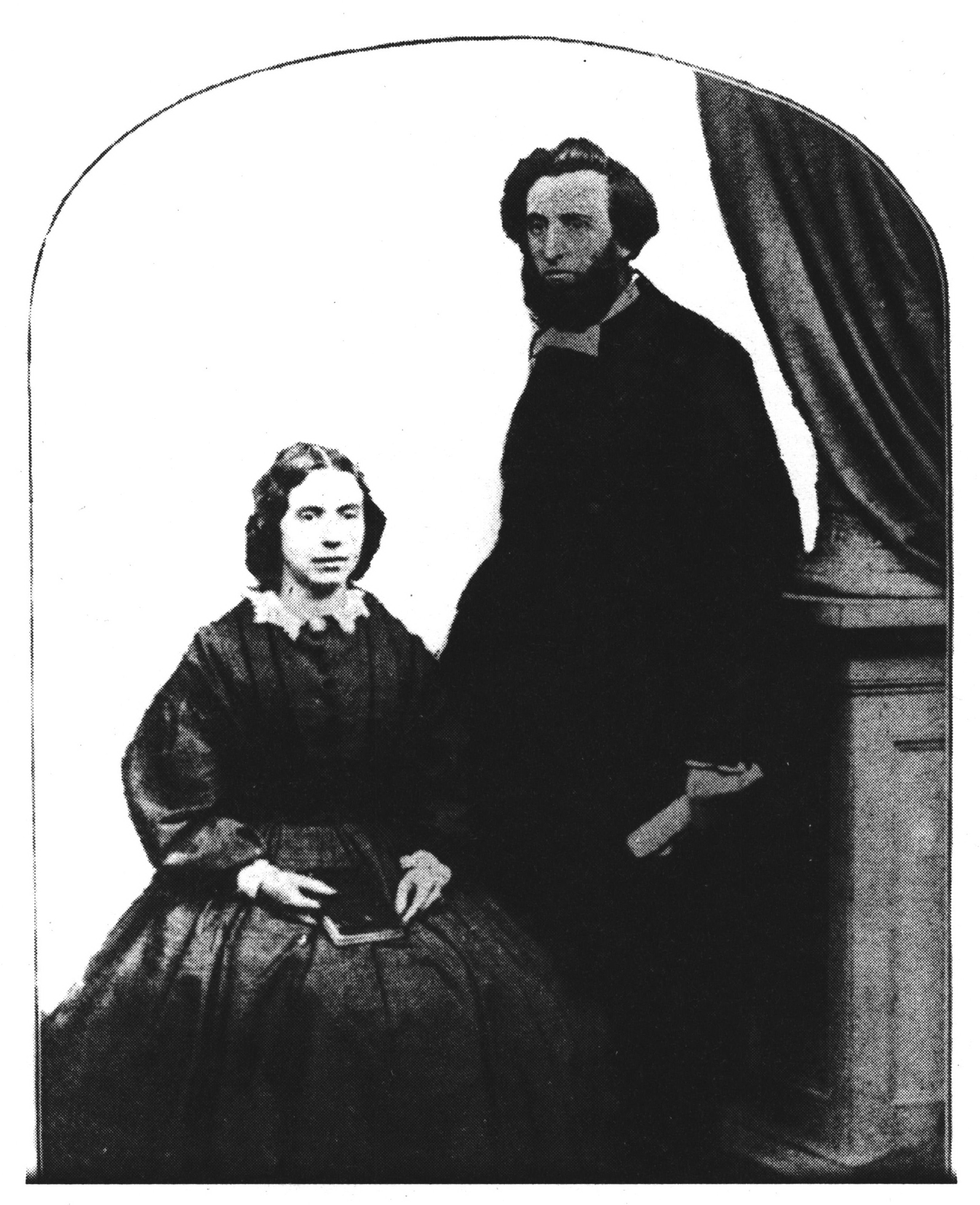

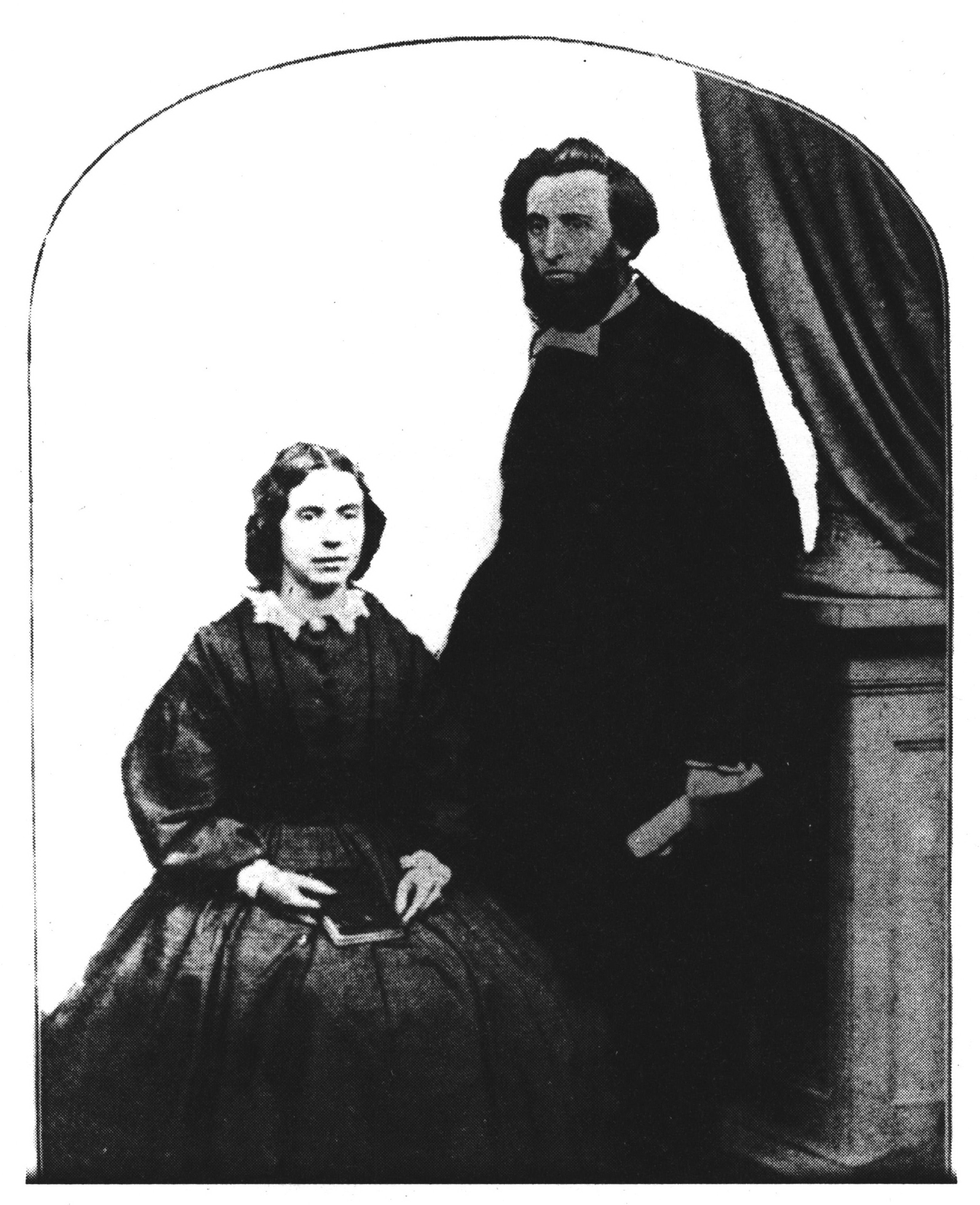

The young evangelists, Cornwall, 1862.

'Strong men, young men, old men weeping like children on account of their sins.'

An Abacus Book

First published in Great Britain in 1999

by Little, Brown and Company This edition published in 2000 by Abacus

Copyright 1999 by Roy Hattersley The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All photographs courtesy of the Salvation Army International Heritage Centre

ISBN: 0 349 11281 9

Typeset in Berkeley Book by M Rules

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives pic

Abacus A Division of

Little, Brown and Company (UK) Brettenham House

Lancaster Place London WC2E 7EN

Introduction

On 17 January 1885, The Times published a letter from the Reverend J. Hector Courcelles MA which described the horrors of a railway journey between Richmond and Notting Hill. 'In the neighbouring compartments,' Mr Courcelles wrote, 'there were some officers of The Salvation Army*. One of them rose and in violent language, began to address us on the most solemn of subjects.' Worse was to come. 'As the train stopped at Latimer station, there was another train on the up line and into the window of this, our zealous friends shouted, "You will all rot in hell."' The letter ended on a plaintive note. 'Should not the railway companies protect their passengers from this sort of behaviour?'

Had The Times of the period not been obsessed with the Salvation Army - describing it in turn as ridiculous, heroic, subversive, heretical, noble and duplicitous - Mr Courcelles' letter would not have been thought important enough for publication. But for all its triviality, the complaint illustrated exactly what respectable opinion hated about William Booth and the great religious movement which he founded.

Much of polite society regarded both the self-styled General and his Army as fanatical, presumptuous, intrusive and vulgar. Those were the characteristics - described by supporters as piety, indomitability, determination and simplicity - which made his extraordinary achievement possible. If William Booth had not been willing to make enemies, he would not have created the only remnant of the hundred-year Wesleyan schism that will survive, independent and self-confident, into the twenty-first century - a new church which, within a dozen years of its inauguration, boasted 3,000 'corps', 10,000 full-time 'officers' and countless adherents in Great Britain alone, and had established outposts in Iceland and New Zealand, Argentina and Germany, the United States of America and South Africa. Unless he had been willing to offend there would have been no campaign for the undeserving poor - the preoccupation of his middle age. Nor would he have helped to change the nation's perception of poverty's causes and cures.

William Booth's success was built on single-minded certainty. At first all that mattered was saving souls - a perfectly rational priority for anyone who believed that we are all born in sin, equally capable of redemption and destined for certain damnation if we fail to grasp the God-given chance of salvation. Even when he became concerned with the material condition of 'Darkest England', he regarded providing help for the 'submerged tenth' (a description he employed a hundred years before it was in common usage) as little more than a way of smoothing their path to heaven. Poverty was the devil's weapon. It drove men to drink and women on to the streets. In an age when even radicals believed that self-help solved all problems, William Booth knew that some men and women were pointed towards eternal damnation by the circumstances in which they were born and lived. Economic determinism - which is what it amounted to - owed more to Marx than to Methodism. But William Booth, who never had time to waste on theories, was not concerned with the philosophical origins of his ideas. They were self-evidently true, so he accepted them.

The poor were his natural congregation and, at least in his early preaching days, the only people to listen to his sermons were the men and women to whom the indolent churches would not reach out. Like John Wesley, his hero and spiritual progenitor, William Booth believed in 'active Christianity' - the moral duty of God's ministers to go out into the highways and byways and make them come in. His style of evangelism was a living reproach to every vicar in whose parish he preached and every minister whose circuit he invaded. He almost certainly never read a word of Milton in his life. But he too had nothing but contempt for the 'blind mouths who scarce themselves know how to hold a Sheep-hook, or have learn'd ought else the least that to the faithful herdsman's art belongs!' The complaint that 'hungry sheep look up and are not fed' might have come straight out of one of his sermons. His wife Catherine was openly offensive about the failures of the traditional churches. Not only were they incapable of making or even keeping converts, they often turned men and women against religion. When she was barely twenty-five - and about to marry William Booth - catherine published the first of her polemics against religious indolence: 'Not more surely will the sprightly infant born in some pent-up garret (which has for generations been impregnable to the pure air of heaven) pine and die than will the spiritual babe introduced into the death-charged atmosphere of some churches.'

After Catherine Booth died - more than twenty years before her husband was 'promoted to glory' - the General's detractors began to claim that the Salvation Army was her creation, and that without her it would wither and die. They were wrong. But without her it would have been a different movement, as William Booth, without her, would have been a different man. Catherine was not his inspiration, but she added a sense of direction to his sense of purpose. William Booth was lucky in many ways - not least in holding an uninhibited view of religion which matched exactly the robust psychology of the Victorian poor. But his greatest piece of good fortune was meeting and marrying one of the most extraordinary women of the nineteenth century.