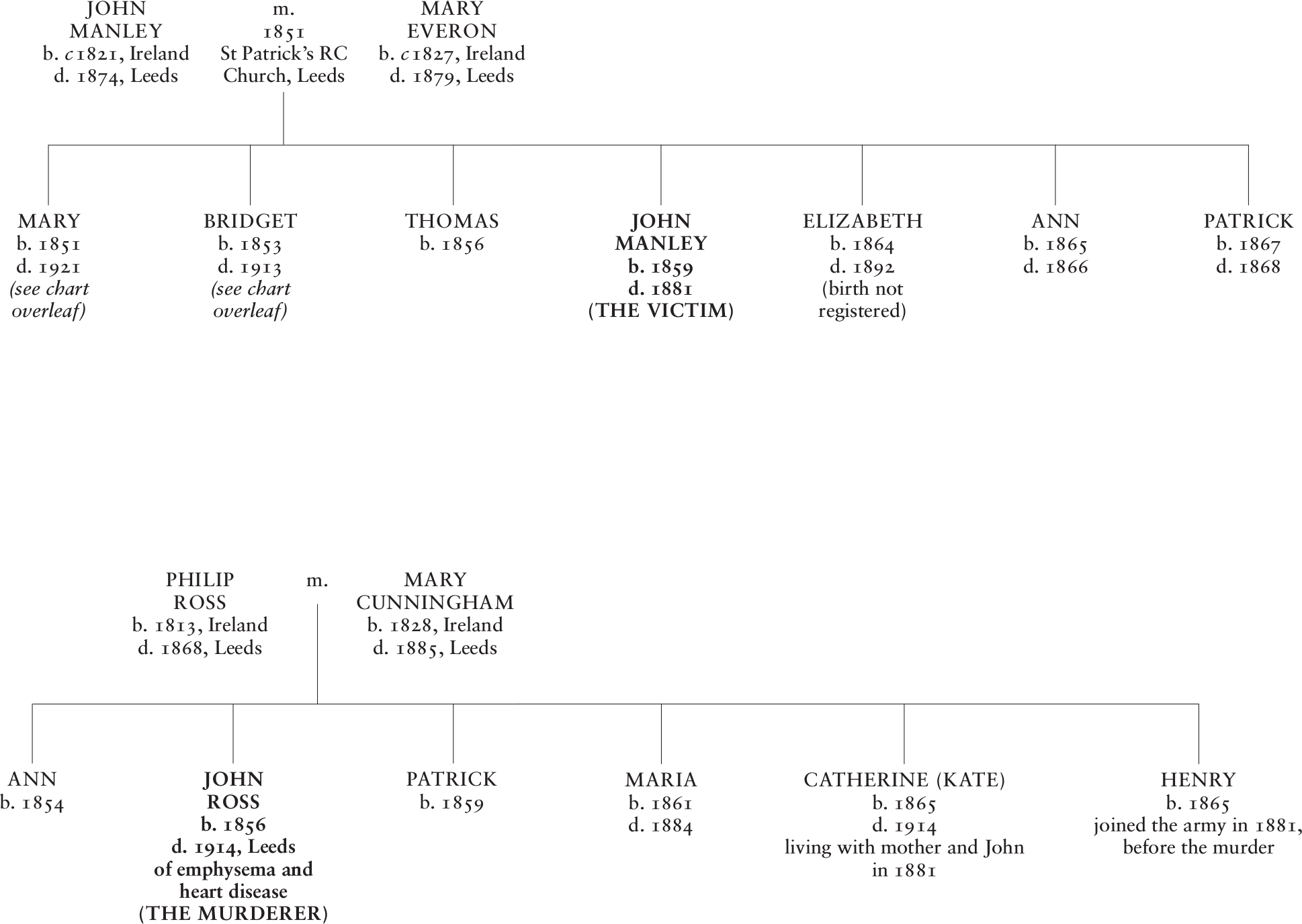

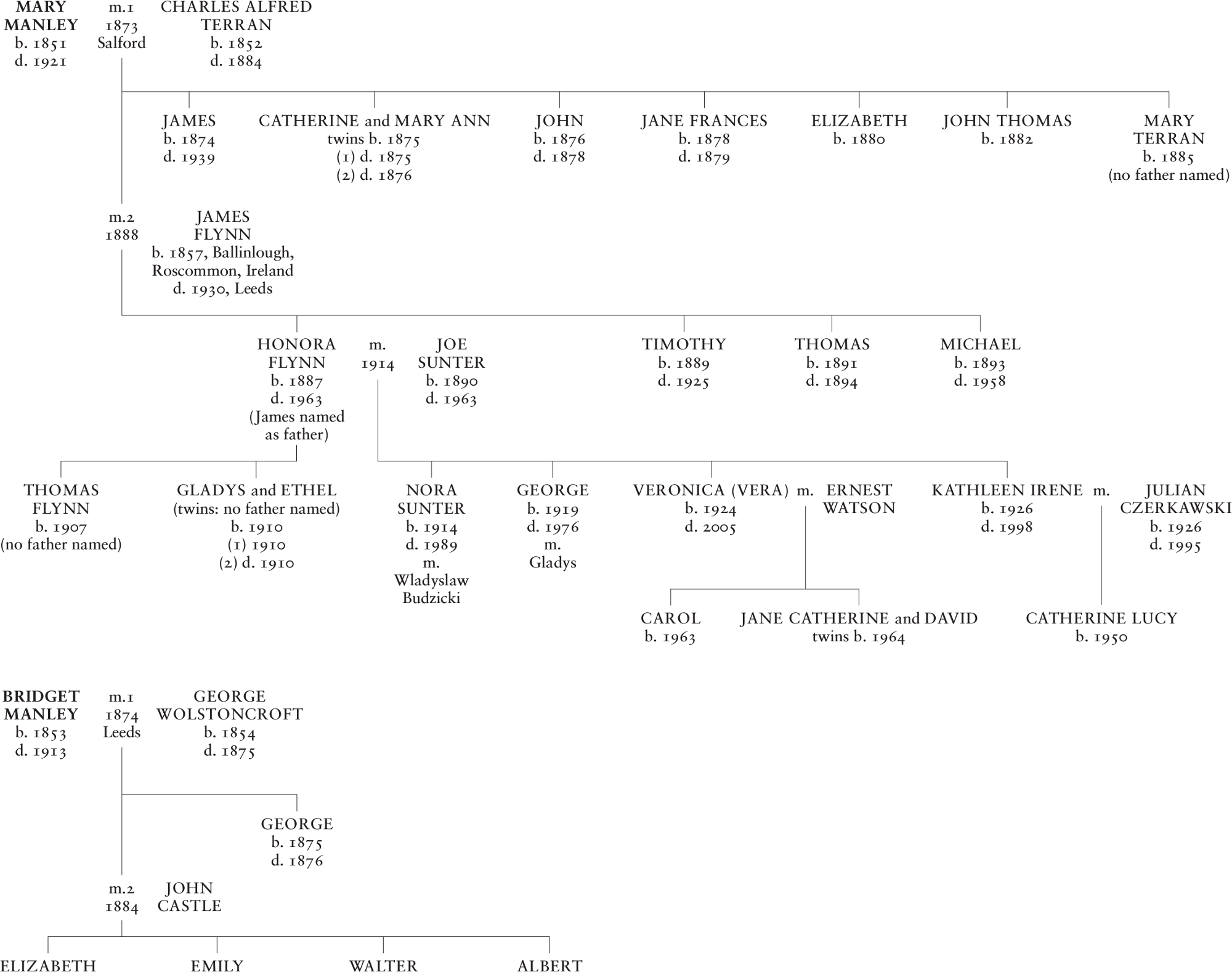

On Christmas Night in 1881, my great-great-uncle, John Manley, whose parents had migrated from Ireland some 30 years earlier, was stabbed in a Leeds street, after a foolish quarrel. The single wound was fatal and he died within minutes. He was just twenty-two years old, and the murderer was only three years older. The two men had known each other for years and may even have been friends. This book began as an attempt to tease out the truth of that tragedy, to understand what happened and why, to establish whether the stories passed down through my family were accurate, or half-truths, shaped into a tale for family consumption. This is a true story about a crime, or as nearly true as I can make it. But it turned out to be about so much more than that. This is a story, especially, about the women in the family who were affected by a crime that seemed to trigger even more tragedy in lives that were already being lived on the very edge of an abyss of poverty and despair. It is a tale that is at once deeper, darker and even more tragic than I could ever have imagined.

On Christmas Night in 1881, twenty-two-year-old John Manley was drinking in what is described as a beerhouse called the Railway Hotel, on York Street in smoky Leeds. There were plenty of other railway hotels, inns and taverns in Leeds, including one called the Old Railway Inn on Marsh Lane, very close to York Street, but this was an area where there were numerous public houses and beerhouses, and names were often replicated, or nearly so. The landlord, as we know from the subsequent trial of the man accused of the murder, was John Hardaker, and in that year, he was running the Railway Hotel at 58 York Street, very close to Brussels Street where John Manley was living with his sisters Bridget and Elizabeth. Their Irish-born parents were both dead. Their elder sister Mary lived just around the corner in Little Off Street, with her husband Charles Terran, a son, James, and a baby daughter, also named Elizabeth, after her young aunt.

John Hardaker was thirty-five years old and on the night of the census in 1881, his household consisted of his wife, Annie, a ten-year-old daughter, Alice, described as a scholar, a young domestic servant called Hannah Cooper and, intriguingly, his or his wifes nine-year-old nephew, also a scholar: Reginald J Beacham from New Orleans. Its hard to resist pursuing Reginalds story: how had his parents come to be in New Orleans? Were they part of that earlier wave of migrants who had finally made it to the promised land of America? You find yourself wondering how the child came to be living above a beerhouse, in a seedy part of Leeds, with his uncle and aunt. Next door at 56 York Street sits a public house called the Red House Inn, so the two pubs were side by side. There is a picture of this building, taken in 1901, twenty years after the murder, an impressive and handsome Georgian town house, running to three storeys, with a balustraded roof, ornamental urns on pedestals, and a gas lamp outside. This looks like a hotel with some letting bedrooms, but on the night of the springtime census in 1881, there are no guests, only the publican and his family.

In the photograph, there are what look like crumbling brick buildings on either side of the Red House Inn, either of which could be an ale house. It may be that the Railway Hotel had closed by 1901, although the Red House Inn was still in existence. Even in 1881, however, the distinction between beerhouses like the Railway Hotel and public houses such as the Red House Inn had become one of status rather than reality. Beerhouses were meant to sell only beer, but in truth the rules were complicated and poorly enforced, and it became all too clear during the subsequent trial that the Railway Hotel was selling spirits as well as ale. Nevertheless, landlord John Hardaker was running a fairly tight ship. Ten years later, he is living elsewhere in Leeds. He and his wife are lodgers in somebody elses house and he is described as a traveller, which covers a multitude of occupations from travelling hawker, the lowest of the low, to commercial travellers selling goods for a particular company. Perhaps the murder and subsequent publicity had adversely affected his business.

The enthusiastic industrialisation of Leeds, throughout the nineteenth century and earlier, coupled with the need for workers and the associated requirement to provide somewhere for those workers to stay, had resulted in a domestic landscape in which heavy industry sat cheek by jowl with countless streets of tiny back-to-back houses. Even in 1908, by which time some slum clearances had taken place, a glance at the Ordnance Survey map for this area reveals a criss-cross of houses in narrow streets, with their associated patchwork of yards, courts, squares and folds that would once have been farmyards. There are mills of all kinds: wool, flax and grain. There are iron works, gas works and foundries. There are buildings associated with textiles, chemicals, leather and pottery as well as all of the heavy machinery essential to the new industries, the construction and servicing of locomotives and the transport of coal from nearby pits to the city. Tall chimneys abound and change the shape of the skyline. The pubs and inns have multiplied, too, in response to the need for some means of escape for those working and living nearby. Beerhouses had originally been one of various worthy ways in which the Victorian authorities tried to control the tendency of working men and women to drown their multitude of sorrows with strong alcohol. In an effort to discourage the disastrous prevalence of cheap gin, the government had removed the tax on beer earlier in the century and issued licences to growing numbers of beerhouses so that they could sell ale alone, often made on the premises. Long before 1881, however, many of these had either closed or become conventional public houses. Perhaps the name beerhouse stuck in this case because the Railway Hotel is repeatedly called that in the newspaper reports, with their various and occasionally conflicting tales of the murder.

When I was young, pubs were mysterious, forbidden places. Doors would swing open and there would be a gush of cigarette smoke and beer fumes, sometimes accompanied by sounds of hilarity and raised male voices. Until I was seven, we lived next door to the Goodmans Arms on Whitehall Road, on the south side of the river Aire, but I was never allowed inside. My grandad Joe, never a big drinker, would go in there for an evening pint sometimes, with his angling friends, but I wasnt aware that anyone else in the family accompanied him. Alcohol wasnt forbidden. My nana, Honora, had the occasional glass of Sanatogen Tonic Wine, and there was always a bottle of black beer in the house for medicinal purposes. This was a sweet, malty concoction, dating back in one incarnation or another to the sixteenth century. Captain Cook is said to have favoured it for its health-giving properties, although its commercial production came much later. It was made close to home, in Wortley, Leeds, by an old company called Mathers, and mostly drunk in very small quantities, in warm milk or cold lemonade. This meant that although the actual alcohol content was 8.5 per cent, it was always used as a cordial. Its syrupy sweetness made it virtually undrinkable on its own, and its iron and vitamin C content were high, too. It had survived well into the twenty-first century as an historic beverage, and ceased production only a few years ago, thanks to the Chancellor getting rid of various anomalous tax exemptions. With the simplified price doubling overnight, black beer become economically unviable and production ceased.