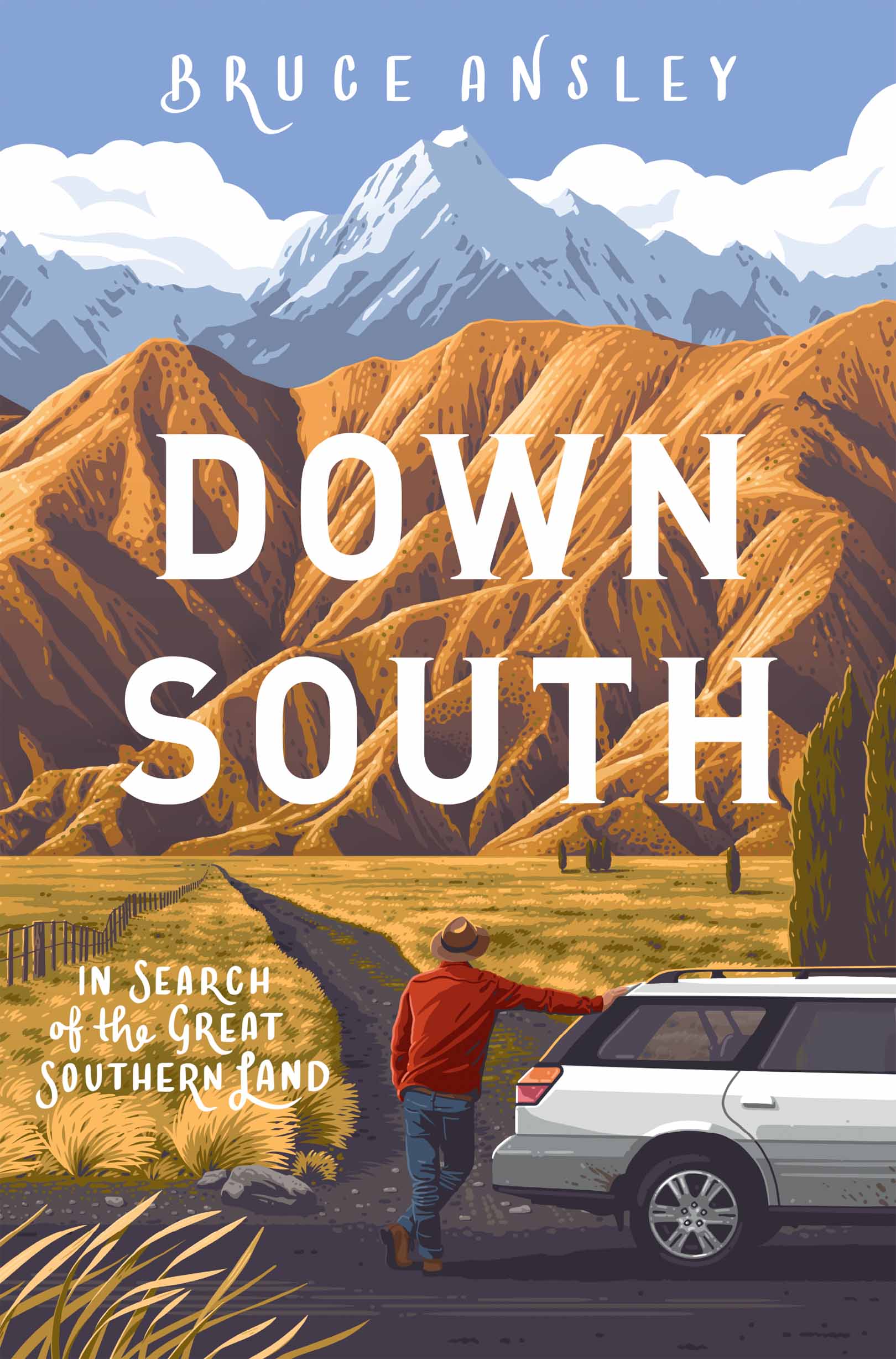

Ansley - Down South: In Search of the Great Southern Land

Here you can read online Ansley - Down South: In Search of the Great Southern Land full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2020, publisher: HarperCollins, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Down South: In Search of the Great Southern Land

- Author:

- Publisher:HarperCollins

- Genre:

- Year:2020

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Down South: In Search of the Great Southern Land: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Down South: In Search of the Great Southern Land" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Ansley: author's other books

Who wrote Down South: In Search of the Great Southern Land? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Down South: In Search of the Great Southern Land — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Down South: In Search of the Great Southern Land" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

CONTENTS

For my sons,

Geoff, Sam and Simon

CONTENTS

Scarcely one hundred and fifty years ago the South Island had most of New Zealands people and just about all of the money. It wasnt called the South Island then, for early European settlers were not romantic. The island was in the middle of the New Zealand mainland, so they named it Middle Island, and the southernmost island became South Island. The best I can say about all that is, at least they got the order right.

The first South Island soon shucked its sobriquet, preferring to be named after Stewart, an early sealer. Both names supplanted the original ones, the considerably more poetic Rakiura, meaning glowing skies, or the alternative Te Puka o Te Waka o Maui, the anchor stone of Mauis canoe. Middle later became South, displacing the musical Te Wai Pounamu, waters of greenstone. The settlers knew their sheep, but poetry was absent from their souls, and the original names were restored only in the twenty-first century.

Abel Tasman, a Dutch gent who in 1642 spent no more than the average annual vacation in the country and hastened away at the first sign of trouble, had mistaken the South Island for a rather grim extension of South America near Cape Horn, and dubbed it Staten Landt. Back home in Holland, cartographers decided Nova Zeelandia had a better ring to it. Evidently they did not think much of Tasmans discovery, for Zeeland was a Dutch province consisting of as much water as land and prone to flooding. Hardly anyone lived there.

Captain James Cook converted the name to New Zealand and it, alas, took. But we cannot not blame Cook for Middle Island. That was settler shorthand, stripped of all imagination and leaving only stark ambition, for those incomers saw Middle Island as a blank balance sheet. Maps of the island showed a fringe of coastal names and an empty interior, and the settlers set about filling it in. Mountains, lakes, plains, forests, fiords: all of them entered those first accounts as pounds sterling. Gold-miners found fortunes in the hills and rivers. Other settlers cleared and covered as much land as possible with sheep, the most remunerative investment for money, exulted one report. After all, the real estate was almost free: The Government allows all persons to purchase land wherever they may please at a fixed price of two pounds an acre... upon 55,000 pounds invested... a clear profit of 36,578 pounds [can be] realised in three years time, plus good annual dividends free from all deductions.

The fact that the island was crisscrossed with Maori trails connecting their great industry, pounamu, with its markets, and dotted with kaika nohoanga, or settlements, was of no consequence. Settlers simply disregarded the tangata whenua. They either took the land or negotiated its purchase, and there was not very much difference between the two. The so-called Kemp Purchase of 1848, for example, resulted in some 5.5 million hectares of Maori land being bought for 2000, which, converted to modern currency, equals parking meter change. The Waitangi Tribunal found that the Crown had taken 14 million hectares of land from Ngai Tahu more than half of the landmass of New Zealand. The iwi was left with only 14,470 hectares. The Crown, the tribunal said, had acted unconscionably and in repeated breach of the Treaty of Waitangi. But the Crown, at the time, consisted of the very settlers who were busy stealing Maori land, their hands, their arms, their entire bodies buried deep in the lolly jar.

So it was not surprising that the name Middle Island suited settler ambitions very well. An anonymous land could be exploited. It needed no fancy name, no higher philosophy. Even the novelist Samuel Butlers objective in taking up the huge Mesopotamia Station in the upper Rangitata Valley was to double his capital and leave the country as soon as possible. He succeeded, and many of his fellow Europeans did too. Soon sheep barons bestrode mountains, valleys and plains, and wealthy southerners ruled the embryonic government.

Middle Island became the centre of their universe and their pot of gold. As Kenneth B. Cumberland and R.P. Hargreaves noted in Middle Island Ascendant (New Zealand Geographer, 1955), The contrasts between the two major islands were sharpened, for now a greater proportion of the population was found in the Middle Island almost two-thirds in 1867 when the search for gold was at its height... In the Middle Island the grazier and prospector penetrated both the dry, treeless continental interior and the mountain highland... In the late 1870s the golden fleece had become the cornerstone of the colonys economy. And the Middle Island possessed the golden fleece.

Everything changed, of course. The gold ran out. The land, particularly the high country, was sucked dry, first by burn-off, later by over-exploitation. Middle Islands population dominance over the north peaked in 1881. Then people began drifting north. By 1901 Middle Island was no longer ascendant.

Middle Island officially became South Island only in 1907. By then its fortunes had begun a slow decline. Yet when I was growing up in Christchurch in the 1960s the South Island still seemed Middle Island Ascendant. Farmers rode on the sheeps back. They drove American Fords and Chevs in an era when a new car was one less than twenty years old. Christchurch was fat and happy.

I went to Canterbury University when it boasted the best-known academics in the land. It was the haven of choice for some of the nations finest architects, artists and writers. If you wanted to be a doctor, surveyor, dietitian or dentist, you went further south, to Otago University. For a good time in a summer paradise, you went to Nelson, where you could not only parade on Tahunanuis beach, but pay for it by picking tobacco.

I never expected to move from the south. Why would I? The television studios were the most prolific in the country, it had thriving newspapers, the best live theatre and universities, great music. But by the end of the millennium the South Islands population was down to a quarter of New Zealands and the ratio was falling.

A new golden fleece was proving elusive. Christchurch was once convinced that it could become the Silicon Valley of New Zealand. The West Coast still believes there is uranium in its mountains. At the top of the island, wonder crops, from blueberries to green tea, came and went.

Many a new candidate raised its head, ran the gauntlet, and collapsed exhausted. But the golden fleece still had to be somewhere... didnt it?

Perhaps it lay in Aucklanders escaping a city where property prices had defied every law of gravity. Average home buyers there had only two choices: to take on mortgages whose repayment times were measured galactically, or to move somewhere south. The South Island resounds with stories of fleeing Aucklanders cashing in, or up, on their high property prices. In Nightcaps, an old coal town in Southland, I once met a woman whod bought her house for $10 and was well pleased with her bargain. That time has passed, but I could still find a house in Nightcaps for only $210,000.

In Blackball, another old mining town on the West Coast, houses scarcely reached double figures before its renaissance. When I last looked, the cheapest house in that town was an early-twentieth-century cottage, on sale for a mere $145,000. At those prices, the south might still be a bolthole.

In the shadow of the Rock and Pillar Range, as deep in the Otago hinterland as you can go, I met Nigel, who had the areas most unlikely occupation: controlling traffic. I was driving along a rough track leading to an ancient gold mine called Golden Point. The track crossed a road leading to the mighty Macraes gold mine, which outsizes Golden Point by a factor of approximately 10 million. Huge trucks crossed the track, carrying rocks from what the mine called a processing plant but I thought of as a dark satanic mill. They seemed to be driven mainly by women, unlikely successors to the grizzled chaps living monastic lives in their little stone huts at Golden Point. Every one of the trucks was capable of squashing my car to the thickness of a Zig Zag tissue.

Next pageFont size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Down South: In Search of the Great Southern Land»

Look at similar books to Down South: In Search of the Great Southern Land. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Down South: In Search of the Great Southern Land and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.