EDUCATING HARLEM

Educating Harlem

A CENTURY OF SCHOOLING AND RESISTANCE IN A BLACK COMMUNITY

EDITED BY

Ansley T. Erickson and Ernest Morrell

Columbia University Press

New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2019 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54404-7

A complete cataloging-in-publication record is available from the Library of Congress.

ISBN 978-0-231-18220-1 (hardback)

ISBN 978-0-231-18221-8 (paperback)

LCCN 2019020857

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

Cover image: Getty Images Michael Ochs Archives

Cover design: Chang Jae Lee

Contents

Ansley T. Erickson and Ernest Morrell

Daniel Perlstein

Thomas Harbison

Kimberley Johnson

Lisa Rabin and Craig Kridel

Jonna Perrillo

Clarence Taylor

Ansley T. Erickson

Marta Gutman

Russell Rickford

Nick Juravich

Kim Phillips-Fein and Esther Cyna

Brittney Lewer

Bethany L. Rogers and Terrenda C. White

Ernest Morrell and Ansley T. Erickson

T his book began in a conversation among a few colleagues in the spring of 2012, but it would not have come to fruition without the support and critical engagement of countless people. We would like to thank Teachers College provost Thomas James, who provided initial funding for this collaboration and what has become the Harlem Education History Project. We also appreciated Khalil Muhammads early support and engagement with our work during his service as director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. From the start, the team at the Columbia Libraries Digital Humanities Center developed the tools that enabled collaboration among authors and that host the book in its open-access form at harlemeducationhistory.library.columbia.edu.

The subsequent conversations that guided this project have taken many forms. Charles Payne, Monica Miller, Tracy Steffes, Kimberley Johnson, Johanna Fernandez, Vanessa Siddle Walker, and Dionne Danns provided feedback as discussants in internal and public conference presentations and helped shape the chapters in their developmental stages. Small and large conversations with Samuel K. Roberts Jr., Jeanne Theoharis, Deirdre Hollman, Joe Rogers Jr., Matthew Delmont, Jack Dougherty, Erica Walker, John Rogers, Paul McIntosh, Deborah Lucas Davis, Karen Taylor, and Terri Watson helped inform us as historians and storytellers. Veronica Holly at the Institute for Urban and Minority Education helped facilitate our work while also sharing her own Harlem history.

Ansley would like especially to thank her Schomburg Center 201718 fellowship cohort under the steady leadership of Brent Hayes Edwards. Ernest would like to thank his former staff at the Institute for Urban and Minority Education for their commitment to this project from the outset.

Our work benefited from a tremendous team of doctoral students in the Program in History and Education at Teachers College, who contributed to this work at various and in some cases multiple stages. We appreciate Antonia Abram Smith, Barry Goldenberg, Viola Huang, Jean Park, Esther Cyna, Deidre Flowers, and Rachel Klepper. Esther Cyna helped steer many aspects of the work, and it is all the more pleasing that she appears in the list of contributors as well. Alongside these young scholars, dozens of Teachers College students helped discuss and refine ideas that appear in this volume.

Most of all, we wish to thank the contributors. Together they represent fourteen different institutions, thirteen different kinds of disciplinary homes in the academy. Along with Heather Lewis, they have been wonderful collaborators, willing to join in summer reading groups and online draft comment sessions, game to learn from one another and helpful in articulating from their various perspectives the need for these histories to be in the world.

None of the contributors would have been able to assemble their work without the numerous archivists and librarians who helped curate and preserve the materials that are the grist for our investigations. We would like to thank especially the teams at the Municipal Archives of the City of New York and the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, whose work can be found on each page of this book.

Despite this abundance of support, any errors remain ours alone.

As an editorial team, although we came from different starting points, we were both new to Harlem and its history. Through the process that yielded this book, and through ongoing work, we have been honored to share the accounts gathered here and look forward to the further historical investigations that Harlems educational history deserves.

Ansley T. Erickson

New York, New York

Ernest Morrell

South Bend, Indiana

BOEBoard of Education of the City of New York Collection

MANew York City Municipal Archives

MSRCMoorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University

NYCBOENew York City Board of Education

NYCIBONew York City Independent Budget Office

NYCPCNew York City Planning Commission

NYSDOENew York State Department of Education

SchomburgSchomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York Public Library

TamimentTamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University

UFTUnited Federation of Teachers

USNYUniversity of the State of New York

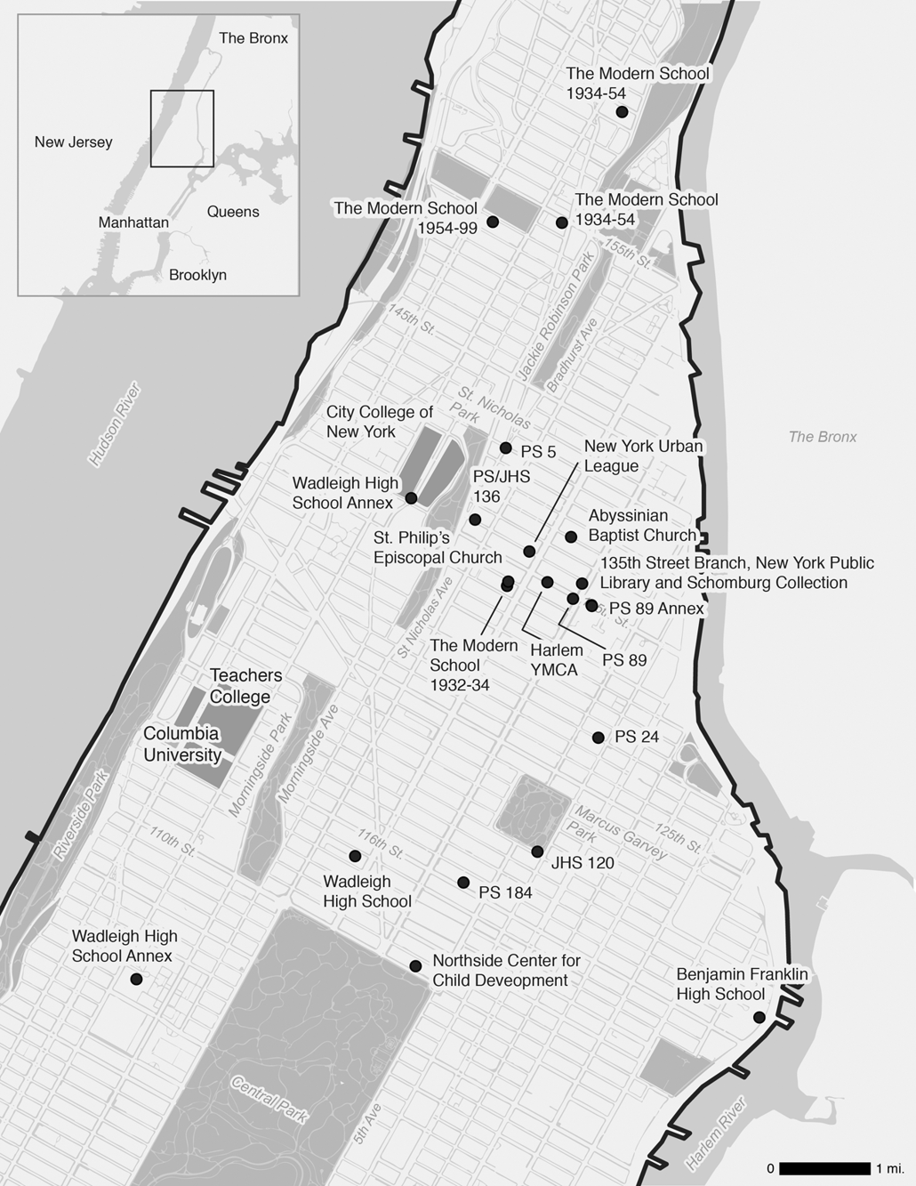

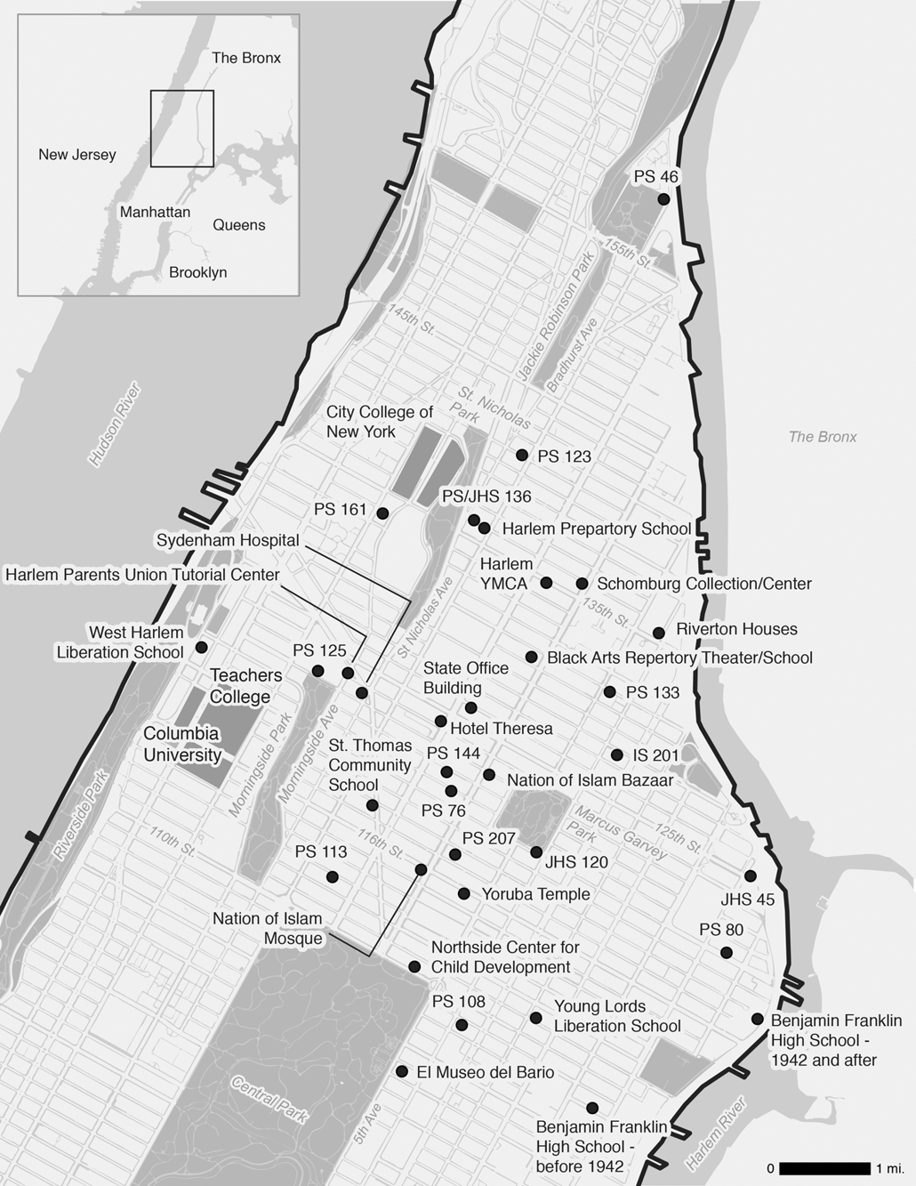

Please note that these maps to do not offer a comprehensive portrayal of Harlems educational landscape. They show those sites that receive substantial discussion in the chapters in this volume.

Map design by Rachael Dottle. Map research by Rachel Klepper. Map layers from: Department of Information Technology and Telecommunications, Department of Urban Planning, City of New York; Atlas of the city of New York, borough of Manhattan. From actual surveys and official plans / by George W. and Walter S. Bromley, New York Public Library Map Warper: http://maps.nypl.org/warper/layers/871; Manhattan Land book of the City of New York. Desk and Library ed. [1956]; New York Public Library Map Warper: http://maps.nypl.org/warper/layers/1453#Metadata_tab; and State of New Jersey GIS: https://www.state.nj.us/dep/gis/stateshp.html. Point locations from: School Directories, New York City Board of Education, New York Amsterdam News via ProQuest Historical Newspapers, and multiple archival sources cited in relevant chapters.

ANSLEY T. ERICKSON AND ERNEST MORRELL

T he speakers corner at 135th and Lenox Avenue in Harlem drew radicals and revolutionaries, tellers of tales and teachers of the public. In a white stone-fronted building only yards away, a noted novelist worked as a librarian, fostering a refuge for children and adult readers. A few long avenues to the west on Edgecombe Avenue, and a few decades later, mothers risked jail to press for better facilities and qualified educators for their children at Junior High School 136. At the same junior high school and others not far away, teenagers gathered to ride buses downtown to City Hall to press the city to fund new youth programs. From the first signs of their concerted migration in 1899 through the end of the twentieth century, people of African descent labored, organized, imagined, and built Harlem.