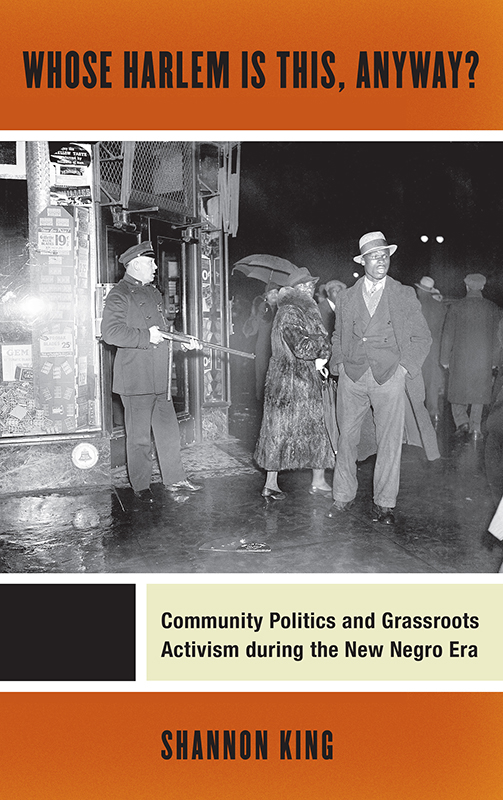

Culture, Labor, History Series

General Editors: Daniel Bender and Kimberley L. Phillips

The Forests Gave Way before Them: The Impact of African Workers on the Anglo-American World, 16501850

Frederick C. Knight

Unknown Class: Undercover Investigations of American Work and Poverty from the Progressive Era to the Present

Mark Pittenger

Steel Barrio: The Great Mexican Migration to South Chicago, 19151940

Michael D. Innis-Jimnez

Fueling the Gilded Age: Railroads, Miners, and Disorder in Pennsylvania Coal Country

Andrew B. Arnold

A Great Conspiracy against Our Race: Italian Immigrant Newspapers and the Construction of Whiteness in the Early 20th Century

Peter G. Vellon

Reframing Randolph: Labor, Black Freedom, and the Legacies of A. Philip Randolph

Edited by Andrew E. Kersten and Clarence Lang

Making the Empire Work: Labor and United States Imperialism

Edited by Daniel E. Bender and Jana K. Lipman

Whose Harlem Is This, Anyway? Community Politics and Grassroots Activism during the New Negro Era

Shannon King

This book, in many ways, is both a work of autobiography and one of scholarship. It emerged, in part, from my own nostalgia, my grappling with and grasping for a past long gone, a past that includes my family and friends in Harlem whom I left behind, my beautiful mother, Jean Cooper, who passed away more than three decades ago, and Rosamond Ketcham, my grandaunt, a widow and nearly retired, who graciously took me into her two-bedroom apartment in the South Bronx and raised me as her own. Aunt Rose passed away in July 2014. Those reminiscences prompted me to reconcile my own late-twentieth-century experiences and personal history in Harlem with the early history of black Harlem, particularly its cultural and intellectual history. This book is my attempt to make sense of those historical tensions.

Without the intellectual, collegial, and emotional support of many people and institutions, the completion of this book would not have been possible. I am deeply grateful to Nicole Fleetwood, Steven G. Fullwood, Jennifer Graber, and Melaine Thompson for getting me over the first hurdle of recommitting to and rewriting the book when I lost a full draft of the manuscript several years ago. When I was prepared to give up, you helped me through that knotty moment.

I would like to thank the Department of History at SUNY Binghamton, particularly Nancy Appelbaum, Elisa Camiscioli, Bonnie Effros, Sarah Elbert, Kathryn Kish Sklar, and Jean Quataert; and my colleagues Phyllis Amenda, Sarah Boyle, Axel Bertamini Corluyan, Jennifer Cubic, Denise Lynn, Laura Murphy, Dmitri and Kara Palmateer, and Ivette M. Rivera-Giusti. To Tiffany R. Patterson, many thanks for your mentorship and continued encouragement; scholars Melvyn Dubofsky, Ricardo Laremont, and Michael O. West, provided me with sage advice and guidance. At Binghamton, I had the opportunity to share my work with and receive feedback from an array of scholars from several academic departments and programs, particularly those attached to the Department of Sociology and the Fernand Braudel Center for the Study of Economies, Historical Systems, and Civilizations: Rigo Andino, Peter Carlo Becerra, Michael Calderon-Zaks, Ruben Chandrasekar, Vik Chaubey, Lena Delgado de Torres, Karen Gagne, Tu Huynh, Gladys Jimnez-Munoz, Williams G. Martin, Lindah Mhando, Wazir Mohamed, Frank Ruiz, Kelvin Santiago-Valles, Vandana Swami, Daryl Thomas, Dale Tomich, Nigel Westmaas and Richard Yidana.

The Schomburg Center for Black Research Scholars-in-Residence Program has played a pivotal role in my development as a scholar and a historian. Diana Lachatanere, words fail to express my deep appreciation and profound respect for you and your management of the scholars program; you are a beacon of inspiration for the fellows and the program alike. Colin Palmer, as the director of the centers scholars program, you created a wonderful environment for the fellows; we presented our work, engaged in robust debate, and received and gave feedback, but more than that, we shared laughter, ate together, and created community. I benefitted from the brilliance of Johanna Fernandez, Nicole Fleetwood, Venus Green, Kali N. Gross, Malinda Lindquist, Ivor Miller, Robert OMeally, Evie Shockley, and Chad L. Williams, who were also fellows. The center was not only a research institution but also, and always, a home away from home. It has been an honor to work with and be in the company of the directors and staff of each division, particularly the late Andr Elize, Sharon Howard, Mary Yearwood, and John Thompson, as well as the security staff, maintenance workers, and the volunteers who daily make the center both one of the worlds finest repositories for research on black culture and a neighborhood epicenter of culture and politics for denizens of Harlem and New York City.

The book project would not have been possible without the knowledge and generosity of the librarians and archivists at Binghamton University, the College of Wooster, the Rare Book and Manuscript Library and the Oral History Research Office at Columbia University, the Library of Congress Reading Room, New York Citys Municipal Archives, the New York Public Library, both the Schomburg Center and the Stephen A. Schwarzman Building, the Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives at New York University, and the University of Oregon.

I want to thank Clara Platter, Constance Grady, and Dorothea S. Halliday at New York University Press, and Culture, Labor, History series editors Daniel Bender and Kimberley Phillips. Kimberley, I am grateful for your longstanding support and your many readings and great feedback on the manuscript. I am also indebted to the two anonymous reviewers who read the book and offered many insightful suggestions.

At the College of Wooster, I have been blessed to be in perhaps the most collegial department on the planet. From the start, the Department of History has shown me what it means to be a colleague, a member of a department, and an exemplary teacher. At least once a week, I have walked into each of your offices asking for advice, and each of you has always had or made time for me. Hayden Schilling, I really appreciate your mentorship, and your always asking me about myself and, of course, the book. Kabria Baumgartner, thank you for reading a chapter and sections of the book; I have often returned to your comments. I am also grateful for the many festive times Ive shared with my colleagues in Kauke Hall and across campus: Christa Craven, Amber Garcia, Raymond Gunn, Matthew Krain, Susan Lee, Lee McBride, Philip Mellizo, Leah Mirakhor, Amyaz Moledina, Charles Peterson, Ibra Sene, Tom Tiernay, and Leslie Wingard; you all have in different ways, helped me keep my life in perspective by reminding me that it was okay, often with a cultural event, spirits or sport, to focus on other things besides the book. In addition to mentorship and overall support, the College of Wooster also provided several subventions for research, travel, and writing, including the Ralston Endowment Fund for Faculty Development and the Henry Luce III Fund for Distinguished Scholarship.