Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

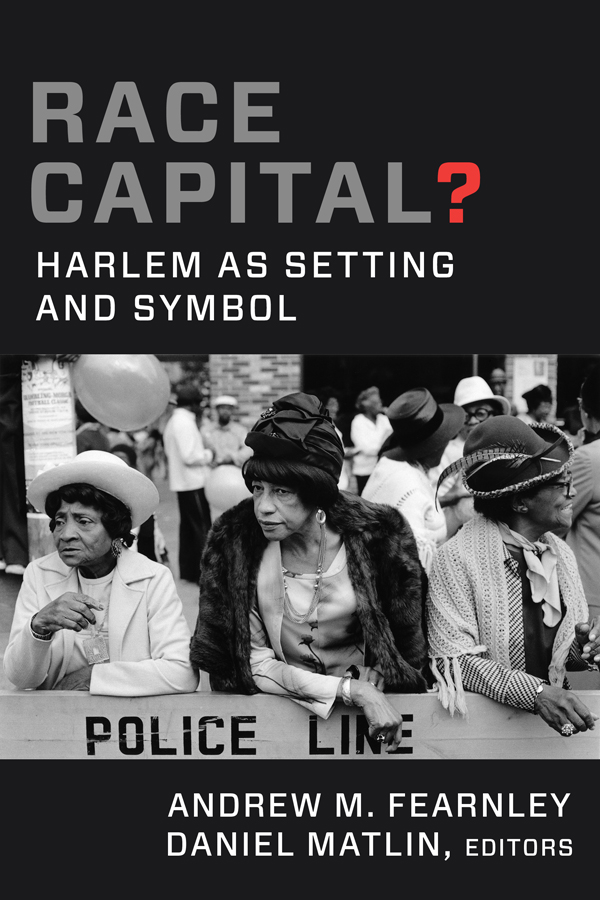

RACE CAPITAL ?

RACE CAPITAL ?

HARLEM AS SETTING AND SYMBOL

ANDREW M. FEARNLEY

DANIEL MATLIN, EDITORS

Columbia University Press/ New York

Columbia University Press

Publishers Since 1893

New York Chichester, West Sussex

cup.columbia.edu

Copyright 2019 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

E-ISBN 978-0-231-54480-1

Library of CongressCataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Fearnley, Andrew M., editor. | Matlin, Daniel, editor.

Title: Race capital? : Harlem as setting and symbol / edited by Andrew M. Fearnley and Daniel Matlin.

Other titles: Harlem as setting and symbol

Description: New York : Columbia University Press, [2018] | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2018014962 (print) | LCCN 2018041029 (ebook) | ISBN 9780231183222 (cloth) | ISBN 9780231183239 (pbk.) | ISBN 9780231544801 (electronic)

Subjects: LCSH: Harlem (New York, N.Y.)Civilization. | Harlem (New York, N.Y.)Intellectual life. | Harlem (New York, N.Y.)Race relations. | New York (N.Y.)Civilization. | New York (N.Y.)Intellectual life. | New York (N.Y.)Race relations. | African AmericansNew York (State)New YorkHistory. | African AmericansNew York (State)New YorkIntellectual life.

Classification: LCC F128.68.H3 (ebook) | LCC F128.68.H3 R33 2018 (print) | DDC 305.8009747/1dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2018014962

ISBN 978-0-231-18322-2 (cloth)

A Columbia University Press E-book.

CUP would be pleased to hear about your reading experience with this e-book at .

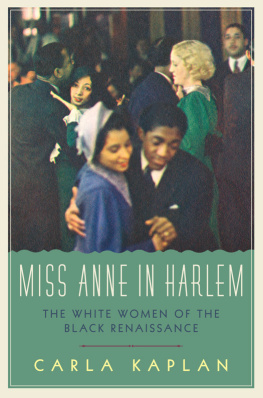

Cover design: Lisa Hamm

Cover photograph: Three Women at a Parade, Harlem NY , 1978. Dawoud Bey. Courtesy of Stephen Daiter Gallery

CONTENTS

ANDREW M. FEARNLEY AND DANIEL MATLIN

ANDREW M. FEARNLEY

CLARE CORBOULD

DANIEL MATLIN

PAULA J. MASSOOD

WINSTON JAMES

MINKAH MAKALANI

CHERYL A. WALL

SHANE WHITE

BRIAN PURNELL

DOROTHEA LBBERMANN

THEMIS CHRONOPOULOS

JOHN L. JACKSON JR.

FARAH JASMINE GRIFFIN

E. Simms Campbell, A Night-Club Map of Harlem , 1932

E. Simms Campbell, Harlem Sketches, New York Amsterdam News , June 8, 1935

E. Simms Campbell, Harlem Sketches, Pittsburgh Courier , January 29, 1938

E. Simms Campbell, Sketches, Pittsburgh Courier , September 26, 1942

E. Simms Campbell, Harlem Sketches, Pittsburgh Courier , July 9, 1938

Map of selected social spaces of Harlems radical interwar intellectual life

Population in Central Harlem, 19502016

Occupied housing units in Central Harlem, and rentals, 19702016

Occupations of Central Harlem residents, in percentages, 19702016

Race and ethnicity in Central Harlem, 19802016

Median household income by race and ethnicity in Central Harlem, 20002016

Median household income in Central Harlem, 19802016

Median gross rent in Central Harlem, 19802016

Percentage of household income spent on housing in Central Harlem, 20002016

Falls Brightest, Boldest Prints Take a Trip to Harlem, Vogue (November 2014)

T his book had its beginnings in a colloquium hosted at Columbia Universitys Institute for Research in African-American Studies, July 2930, 2015. We thank Samuel K. Roberts, Sharon Harris, and Shawn Mendoza for the generosity and warm welcome they extended to us at the institute. A grant from the Manchester Urban Institute provided essential funding during the early phase of the project, and we thank Kevin Ward for his role in facilitating this. We are grateful to all who participated in the colloquium and to all of the contributors to the book for their ideas, commitment, hard work, and patience. We also wish to thank the anonymous reviewers of the manuscript for their close and insightful readings, Christian Winting of Columbia University Press for his expertise and assistance, and Todd Manza for his valuable contribution at the copyediting stage. We owe a huge debt of gratitude to our editor, Bridget Flannery-McCoy, for her dedication to this project and all the advice and support she has given to us. Finally, our deepest thanks, as always, go to Jen and Samantha, and to Heather.

Andrew Fearnley and Daniel Matlin

Manchester and London

ANDREW M. FEARNLEY AND DANIEL MATLIN

O bituaries for black Harlem have appeared with notable regularity over the past few years. For close to a century, the name Harlem has been loaded with symbolic meanings that have made this narrow stretch of upper Manhattan perhaps second only to Africa as a spatial signifier of blackness. But a stream of recent commentary across the United States and around the world has now made Harlem almost a byword for gentrification. By the turn of the twenty-first century, shifting demographics, rising investment, a combination of renovation and new construction, and a proliferation of boutiques and fashionable restaurants were prompting palpable excitement about Harlem in some quarters of the media. After decades of disinvestment, declining population, high crime rates, and physical decay, during which Harlem had been a no-go zone in the eyes of many New Yorkers, a new Harlem Renaissance was said to be at hand, recalling the glamour of the neighborhoods fabled 1920s heyday and, relatedly, marking its revival as a site of recreation, consumption, and exotic spectatorship for whites. Increasingly, however, celebratory stories about Harlems revival and rediscovery have been overtaken by anguished pronouncements that its eclipse as a black neighborhood is imminent. Commentators have pored over data showing the increase in Harlems white and Hispanic populations for signs that a point of no return has been reached.

Harlem has scarcely been alone, of course, in undergoing a rapid demographic transition and the broader processes of urban change known as gentrification. Across much of the world, a renewed vogue for city living has combined with deregulation of housing markets and urban regeneration policies to help usher an influx of affluent residents and consumers into neighborhoods long home to working-class, low-income, and (often) minority communities, whose hold on these neighborhoods then becomes financially precarious. In Harlems case, though, both the celebration and the anguish accompanying neighborhood change have been especially intense and voluble. Almost from its inception, black Harlems preeminence as a site of African American and black diasporic life and consciousness has been asserted, redefined, and rehearsed so widely and frequently that the prospect of its demise assumes an importance radically out of proportion to the neighborhoods slender dimensions.

As the potency of Harlems iconic blackness has been challenged by the quickening pace of demographic and material changes on the ground, recent work in African American and black diasporic studies has simultaneously mounted a second kind of challenge to the neighborhoods standing, through a variety of disavowals of the Harlem-centrism of previous scholarship. Even the idea of a Harlem Renaissance has increasingly been called into question. As the transnational turn in the humanities has opened up, and drawn new connections across, the geographic terrain of black social, political, cultural, and intellectual life, Harlem, long feted as the capital of black America and even as the capital of the black world, has found itself downgraded, recast as one province among many scattered throughout a variegated, interconnected, and multipolar black world.