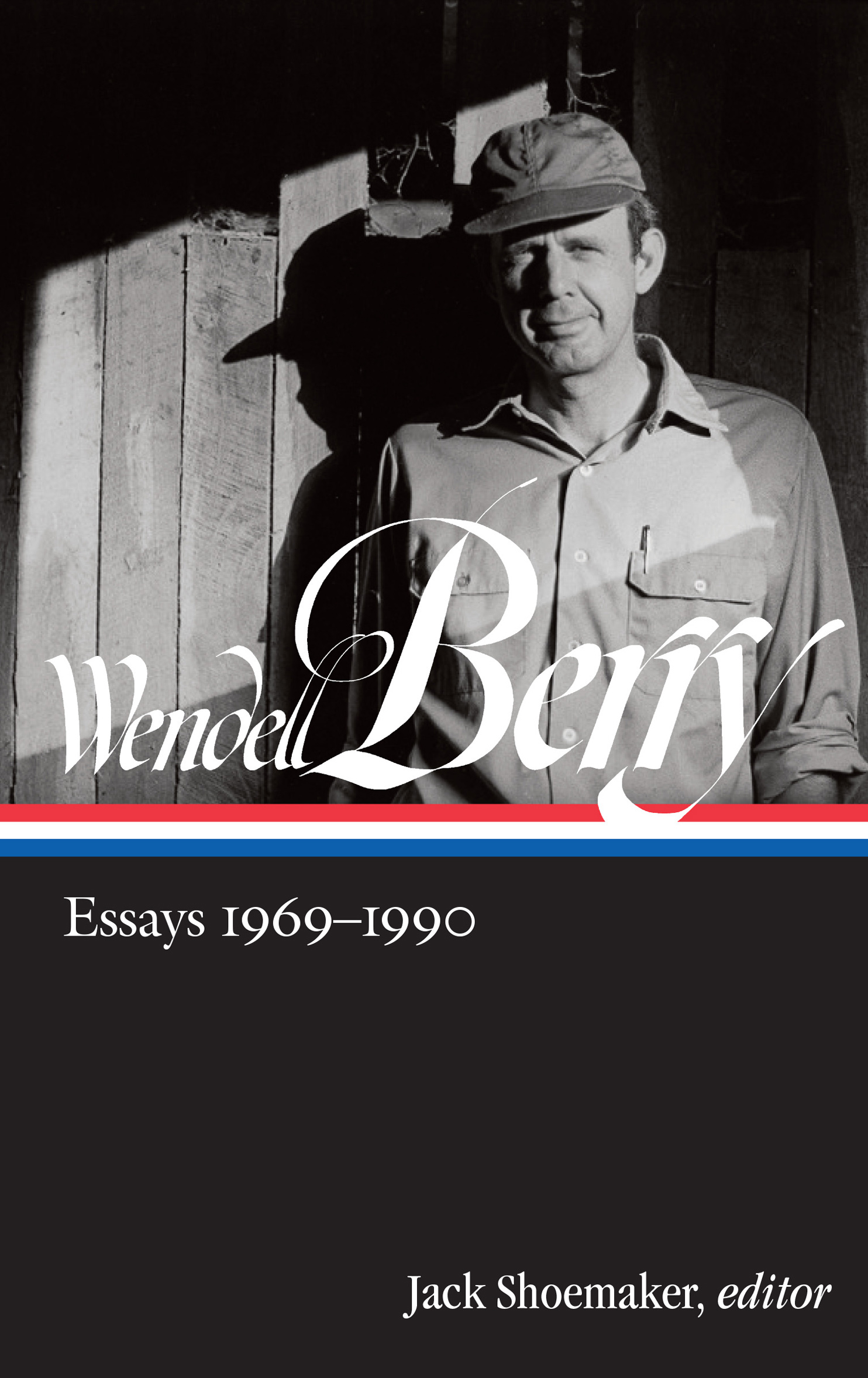

Wendell Berry - Wendell berry : essays 1969-1990 (loa #316)

Here you can read online Wendell Berry - Wendell berry : essays 1969-1990 (loa #316) full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2019, publisher: The Library of America, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Wendell berry : essays 1969-1990 (loa #316)

- Author:

- Publisher:The Library of America

- Genre:

- Year:2019

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Wendell berry : essays 1969-1990 (loa #316): summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Wendell berry : essays 1969-1990 (loa #316)" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Wendell berry : essays 1969-1990 (loa #316) — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Wendell berry : essays 1969-1990 (loa #316)" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

INCLUDING

AND SELECTIONS FROM

LIBRARY OF AMERICA E-BOOK CLASSICS

WENDELL BERRY: ESSAYS 19691990

Volume compilation, notes, and chronology copyright 2019 by

Literary Classics of the United States, Inc., New York, N.Y.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner whatsoever without

the permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief

quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Published in the United States by Library of America

LIBRARY OF AMERICA, a nonprofit publisher,

is dedicated to publishing, and keeping in print,

authoritative editions of Americas best and most

significant writing. Each year the Library adds new

volumes to its collection of essential works by Americas

foremost novelists, poets, essayists, journalists, and statesmen.

Visit our website at www.loa.org to find out more about

Library of America, and to sign up to receive our

occasional newsletter with exclusive interviews with

Library of America authors and editors, and our popular

Story of the Week e-mails.

eISBN 9781598536072

THE LONG-LEGGED HOUSE

(1969)

W E PUT THE canoe in about six miles up the Kentucky River from my house. There, at the mouth of Drennon Creek, is a little colony of summer camps. We knew we could get down to the water there with some ease. And it proved easier than we expected. The river was up maybe twenty feet, and we found a path slating down the grassy slope in front of one of the cabins. It went right into the water, as perfect for launching the canoe and getting in as if it had been worn there by canoeists.

To me that, more than anything else, is the excitement of a rise: the unexpectedness, always, of the change it makes. What was difficult becomes easy. What was easy becomes difficult. By water, what was distant becomes near. By land, what was near becomes distant. At the water line, when a rise is on, the world is changing. There is an irresistible sense of adventure in the difference. Once the river is out of its banks, a vertical few inches of rise may widen the surface by many feet over the bottomland. A sizable lagoon will appear in the middle of a cornfield. A drain in a pasture will become a canal. Stands of beech and oak will take on the look of a cypress swamp. There is something Venetian about it. There is a strange excitement in going in a boat where one would ordinarily go on footor where, ordinarily, birds would be flying. And so the first excitement of our trip was that little path; where it might go in a time of low water was unimaginable. Now it went down to the river.

Because of the offset in the shore at the creek mouth, there was a large eddy turning in the river where we put in, and we began our drift downstream by drifting upstream. We went up inside the row of shore trees, whose tops now waved in the current, until we found an opening among the branches, and then turned out along the channel. The current took us. We were still settling ourselves as if in preparation, but our starting place was already diminishing behind us.

There is something ominously like life in that. One would always like to settle oneself, get braced, say Now I am going to beginand then begin. But as the necessary quiet seems about to descend, a hand is felt at ones back, shoving. And that is the way with the river when a current is running: once the connection with the shore is broken, the journey has begun.

We were, of course, already at work with the paddles. But we were ahead of ourselves. I think that no matter how deliberately one moved from the shore into the sudden fluid violence of a river on the rise, there would be bound to be several uneasy minutes of transition. It is another world, which means that ones senses and reflexes must begin to live another kind of life. Sounds and movements that from the standpoint of the shore might have come to seem even familiar now make a new urgent demand on the attention. There is everything to get used to, from a wholly new perspective. And from the outset one has the currents to deal with.

It is easy to think, before one has ever tried it, that nothing could be easier than to drift down the river in a canoe on a strong current. That is because when one thinks of a river one is apt to think of one thinga great singular flowing that one puts ones boat into and lets go. But it is not like that at all, not after the water is up and the current swift. It is not one current, but a braiding together of several, some going at different speeds, some even in different directions. Of course, one could just let go, let the boat be taken into the continuous mat of driftleaves, logs, whole trees, cornstalks, cans, bottles, and suchin the channel, and turn and twist in the eddies there. But one does not have to do that long in order to sense the helplessness of a light canoe when it is sideways to the current. It is out of control then, and endangered. Stuck in the mat of drift, it cant be maneuvered. It would turn over easily; one senses that by a sort of ache in the nerves, the way bad footing is sensed. And so we stayed busy, keeping the canoe between the line of half-submerged shore trees and the line of drift that marked the channel. We werent trying to hurrythe currents were carrying us as fast as we wanted to gobut it took considerable labor just to keep straight. It was like riding a spirited horse not fully bridle-wise: We kept our direction by intention; there could be no dependence on habit or inertia; when our minds wandered the river took over and turned us according to inclinations of its own. It bore us like a consciousness, acutely wakeful, filling perfectly the lapses in our own.

But we did grow used to it, and accepted our being on it as one of the probabilities, and began to take the mechanics of it for granted. The necessary sixth sense had come to us, and we began to notice more than we had to.

There is an exhilaration in being accustomed to a boat on dangerous water. It is as though into ones consciousness of the dark violence of the depths at ones feet there rises the idea of the boat, the buoyancy of it. It is always with a sort of triumph that the boat is realizedthat it goes on top of the water, between breathing and drowning. It is an ancient-feeling triumph; it must have been one of the first ecstasies. The analogy of riding a spirited horse is fairly satisfactory; it is mastery over something resistanta buoyancy that is not natural and inert like that of a log, but desired and vital and to ones credit. Once the boat has fully entered the consciousness it becomes an intimate extension of the self; one feels as competently amphibious as a duck, whose feet are paddles. And once we felt accustomed and secure in the boat, the day and the river began to come clear to us.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

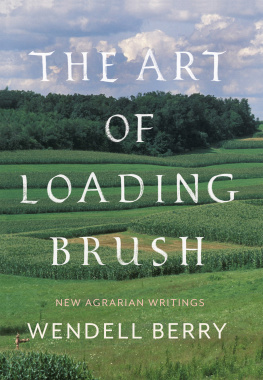

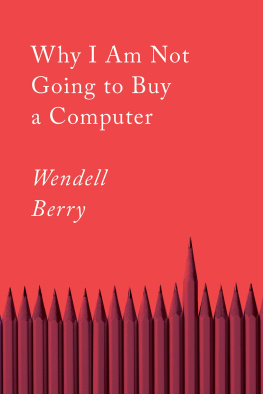

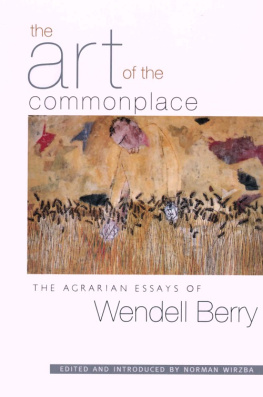

Similar books «Wendell berry : essays 1969-1990 (loa #316)»

Look at similar books to Wendell berry : essays 1969-1990 (loa #316). We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Wendell berry : essays 1969-1990 (loa #316) and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.