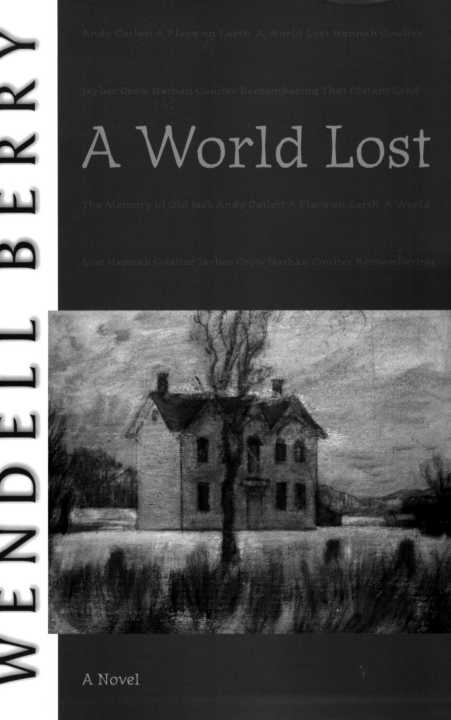

WENDELL BERRY

Andy Catlett

Hannah Coulter

Jayber Crow

The Memory of Old Jack

Nathan Coulter

A Place on Earth

Remembering

That Distant Land

A World Lost

Also by Wendell Berry

FICTION

Andy Catlett

Hannah Coulter

Fidelity

Jayber Crow

The Memory of Old Jack

Nathan Coulter

A Place on Earth

Remembering

That Distant Land

Watch With Me

The Wild Birds

POETRY

The Broken Ground

Clearing

Collected Poems: 1957-1982

The Country of Marriage

Entries

Farming: A Hand Book

Findings

Openings

A Part

Sabbaths

Sayings and Doings

The Selected Poems of Wendell Berry (1998)

A Timbered Choir

The Wheel

ESSAYS

The Way of Ignorance

Another Turn of the Crank

The Art of the Commonplace

Citizenship Papers

A Continuous Harmony

The Gift of Good Land

Harlan Hubbard: Life and Work

The Hidden Wound

Home Economics

Life Is a Miracle

Long-Legged House

Recollected Essays: 1965-198o

Sex, Economy, Freedom and Community

Standing by Words

The Unforeseen Wilderness

The Unsettling of America

What Are People For?

WENDELL BERRY

A World Lost

a novel

The dead rise and walk about The timeless fields of thought

A World Lost

1

It was early July, bright and hot; I was staying with my grandmother and grandfather Catlett. My brother, Henry-who might have been there with me; we often made our family visits together-was at home at our house down at Hargrave. For several good and selfish reasons, I did not regret his absence. When we were apart we did not fight, we did not have to decide who would get what we both wanted, we did not have to trump up disagreements just to keep from agreeing. The day would come when there would be harmony between us and we would be allies, but we had many a trifle to quarrel over before then.

Uncle Andrew, who often ate dinner at Grandma Catlett's, was at work upon the river at Stoneport, as he had been for a week already. He had refused to take me with him. This was in the summer of 1944, when I was nine, nearly ten. The war had made building materials scarce. My father and Uncle Andrew, along with Uncle Andrew's buddies, Yeager Stump and Buster Simms, had bought the buildings of a defunct lead mine at Stoneport with the idea of salvaging the lumber and sheet metal to build some barns. The work was heavy and somewhat dangerous; it was going to take a long time. I could not go because I was too short in the push-up. I felt a little blemished by Uncle Andrew's refusal, and I missed him. Now and again I experienced the tremor of my belief that the adventure of Stoneport had been subtracted from me forever. But I was reconciled. As I was well aware, there were advantages to my solitude.

No day at Grandma and Grandpa's was ever the same as any other, but there were certain usages that I tried to follow, especially when I was there alone. That afternoon, as soon as I could escape attention, I knew I would go across the field to Fred Brightleaf's. Fred and I would catch Rufus Brightleaf's past-work old draft horse, Prince, and ride him over to the pond for a swim. And after supper, when Grandma and Grandpa would be content just to sit on the front porch in the dark, and you could feel the place growing lonesome for other times, I would drift away down to the little house beside the woods where Dick Watson and Aunt Sarah Jane lived. While the light drained from the sky and night fell I would sit with Dick on the rock steps in front of the door and listen to him tell of the horses and mules and foxhounds he remembered, while Aunt Sarah Jane spoke biblical admonitions from the lamplit room behind us; to her, Judgment Day was as much a matter of fact, and as visible, as the Fourth of July.

I was comfortable with the two of them as I was with nobody else, and I am unsure why. It was not because, as a white child, I was free or privileged with them, for they expected and sometimes required decent behavior of me, like the other grown-ups I knew. They had not many possessions, and the simplicity in that may have appealed to me; they did not spend much time in anxiety about things. They had too a quietness that was not passive but profound. Dick especially had the gift of meditativeness. Because he was getting old, what he meditated on was the past. In his talk he dreamed us back into the presence of a supreme work mule named Fanny, a preeminent foxhound by the name of Strive, a longrunning and uncatchable fox.

There had been, anyhow, only three of us at the table in Grandma's kitchen that noon: Grandma and Grandpa and me. After dinner, Grandpa got up and went straight back to the barn. I sat on at the table, liking the stillness that filled the old house at such times. The whole world seemed stopped and quiet, as if the sun stood still a moment between its rising up and its going down; you could hear the emptiness of the rooms where nobody was. And then Grandma set the dishpan on the stove and started scraping up our dishes. She had her mind on her work then, and I headed for the door.

"Where are you off to, Andy, old traveler?"

"Just out," I said.

She let me go without even a warning. The good old kitchen sounds were rising up around her. As I went out across the porch I heard her start humming "Rock of Ages." When she was young she had been a good singer, but her voice was cracked now and she could not sustain the notes.

I went down through the field we still called the Orchard, though only one old apple tree was left, and then into the Lower Field, across the part of it that had been cut for hay, and then followed the dusty two-track road around the edge of a field of corn. I saw the groundhog that I planned to shoot as soon as I got old enough to have a.22 rifle. Grandma always put dinner on the table at eleven-thirty, and so it was still close to noon. My shadow was almost underfoot, and I amused myself by stepping on its head as I went along. I was wearing a coarse-woven straw hat that Uncle Andrew had bought for me, calling it "a two-gallon hat, plenty good for a half-pint." The sun shone through holes in the brim in a few places, making little stars in the shadow. I walked fast, telling myself the story of myself: "The boy is walking across the farm. He is by himself. Nobody knows where he is going. It is a pretty day."