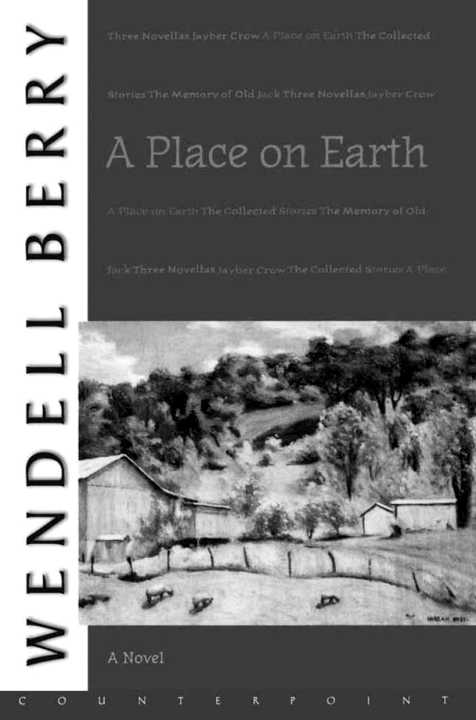

WENDELL BERRY

The Collected Stories

Jayber Crow

The Memory of Old Jack

A Place on Earth

Three Novellas

Also by Wendell Berry

FICTION

The Discovery of Kentucky

Fidelity

Nathan Coulter

A Place on Earth

Remembering

Two More Stories of the Port William Membership

Watch with Me

The Wild Birds

A World Lost

POETRY

The Broken Ground

Clearing

Collected Poems: 1957-1982

The Country of Marriage

Entries

Farming: A Hand Book

Findings

Openings

A Part

Sabbaths

Sayings and Doings

The Selected Poems

A Timbered Choir

Traveling at Home (with prose)

The Wheel

ESSAYS

Another Turn of the Crank

A Continuous Harmony

The Gift of Good Land

Harlan Hubbard: Life and Work

The Hidden Wound

Home Economics

Recollected Essays: 1965-1980

Sex, Economy, Freedom & Community

Standing by Words

The Unforseen Wilderness

The Unsettling of America

What Are People For?

WENDELL BERRY

A Place on Earth

[revision]

For Mary and Chuck For Katie, Virginia, and Tanya For Den and Billie For Emily and Marshall

Contents

PART TWO

PART THREE

PART FOUR

PART FIVE

Author's Note

This book has had an editorial history sufficiently humbling to its author. I began it in January, 1960, and it was published by Harcourt, Brace and World in 1967. Dan Wickenden, then editor at Harcourt, helped me with patient intelligence to shorten and improve my unwieldy manuscript. But as I recognized after publication, the book was not satisfactory. Later, Jack Shoemaker of North Point Press offered me the opportunity of a new edition, to be published in 1983, for which I made many cuts, some large, and a lot of editorial changes. For this Counterpoint edition of 2001, thanks once more to Jack Shoemaker, I have made a good many further changes, both to improve the writing and to correct geographical and historical discrepancies between this and my other books about Port William.

A Place on Earth

Part One

1

The Empty Store

The seed bins are empty. The counters and rows of shelves along the walls, stripped of merchandise, contain only slanting shadows and the slanting rainy light from the front windows. The interior of the store has been reduced to a severe geometrical order over which the light breaks without force, colored but not brightened by the white of the walls, the pale green of the counters and shelves. Its swept surfaces outline precisely the dimension of its silence and emptiness, but the strict order and cleanness of the room make it a silence that seems actively expectant of sound, a carefully tended emptiness anticipating an arrival. In the back, near the entrance to a small screened-off area once used as an office, a black iron safe stands against the wall. When Frank Lathrop cleaned out the store after his son jasper went into the Army at the beginning of the war, he left the door of the safe ajar for fear that if he closed it he would never be able to work the combination to open it again. He did not foresee that he would ever want to open it again, but at the time the precaution seemed necessary, consistent with the careful neatness in which he had left the place.

The four men who sit at the card game in the makeshift office feel the vacancy of the larger room as a condition of the smaller, which, like the seepage of wind through the back wall, subtly qualifies their presence there. All afternoon the sound of rain on the tin roof has pecked and swiveled through the hollow building, constantly changing in force and inflection, but never ceasing, until it seems to them the very presence and noise of emptiness. They have got used to the sound; consciousness, attentive to the details of the game, has overridden it, but at the back of their minds it persists. And the rain itself has persisted for days into the beginning of March, making the dawns sluggish, the evenings early and sudden, so that they have come to think of time as a succession of nights rather than days.

A large desk, its cover pulled down and locked, stands at the end of the room farthest from the door. On its top are several neatly marked boxes of accounts and receipts, and a radio playing so quietly that the music is no more than a series of stuttering accents like the far-off rattling of a snare drum. Between the desk and the heating stove at the opposite end of the room jasper Lathrop's meat block has been placed to serve as a card table. The two windows in the back wall look out on a narrow lot covered with dead weed stalks, chicory and poke and burdock, and the lighter brown napping of foxtail and wild oat. In the center of the lot there is a disjointed heap of weather-blackened crates that Frank Lathrop once intended to burn; but on the day, a week or so after jasper's departure, when he set the store in order and shut the building, he felt his duty to his son was more finished than he wanted to believe. The act of burning seemed too final, too suggestive of a conclusion he was unable to face. In the three years that have gone by since then, the crates have stayed there, and now in the steady rain they have the look of permanence, the stack of them monolithic and at ease, an indelible feature of the casual back view of the town. At the rear of the lot, built sidelong to the fence, is the small carpenter shop of Ernest Finley. Black coal smoke comes from its chimney, twisted off the bricks by the wind and driven to the ground, turning delicately amber as it thins. The carpenter's pickup truck is parked in front of the door, and through the afternoon the men at the card game have heard the measured sounds of his hammering and sawing. Beyond the shop a broad pasture swags down to a creek branch and tilts up again, gently, to the top of a long ridge. A flock of sheep, heads down against the rain, straggles toward the barn at the top of the ridge for the night feeding. Beyond the ridge is the opening of the river valley.