Writing a book is impossible without the help of a community of supporters. Thank you to MAC for your advice, encouragement, ideas and rock-steady support. There were times along the way when I had doubts. Thank you for believing in me.

Thank you to Will DeRooy for helping me find the words.

Thank you to Karen Robb for providing the inspiration for the book. You prove that rock stars arent always the people on the stage.

Every author needs readers, and I want to thank Camilla McKinney, Rick Gilmore, Elizabeth Hoffman Schmeltz, Richard and Milton Anderson, Tony Jennings and Kelley ONeill, Becky Levin, Kimberly Overbeek, Diana Meredith and Scott Russell for your patience and advice. I know the rough cuts were just thatrough. I appreciate your time.

And thank you to the staff of the Library of Congressif not for your sheer strengthfor your advice, for your recommendations and for responding to my many stupid questions with generosity and patience.

In 1956, two Stanford University professors, Alexander and Juliette George, published a groundbreaking personality study In each of these works, the authors sought to understand the biographical experiences that drove the presidents behaviors and decision-making. A similar motivation lies at the heart of Partner to Power.

This psychologically oriented biography is a non-technical, non-scientific personality study of nine presidents and their closest advisers. The objective is to understand the psychological, biographical and political motivations that drew these individuals into partnership, with the goal of understanding why they needed each other and how they worked together.

Any adequate examination of the lives of these individuals must consider the development of the total personality, up to and including adulthood. Indeed, by the time the nine men profiled here attained the presidency, they were mature enough to have understood their childhood influences and had undoubtedly made personality adjustments that they hoped would be efficacious to their political advancement. In light of this, the goal of Partner to Power is to take into account not only the childhood influences on the development of these men and women, but the early adulthood influences as well.

Partner to Power is written for a general reader who is interested in history on the whole and in the lives and accomplishments of American presidents in particular. Additionally, considerable attention has been given to satisfying the interest of readers who are looking for a deeper analysis of the role of American presidents right-hand men and women. Accordingly, the chapters can be accessed from a number of angles.

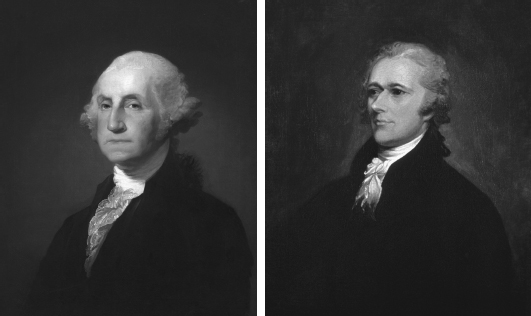

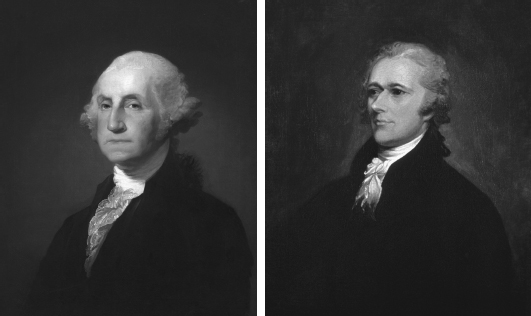

Partner to Power can be read as a collection of historical narratives, as a series of personality studies or as a study of the evolution of the role of right hand to the president. Each chapter profiles a key relationship that helped define and drive the development of the role since the first right handAlexander Hamilton. The chapters chronicle the development of the role in a cursory way, and the epilogue examines it in more detail. This is to avoid distracting the general reader from what might be best described as biographical narratives, crafted for entertainment as well as educational value. Those readers more interested in an analysis of the role of right hand will notice that while the chapters touch upon the strengths and weaknesses of each of the models represented here, the epilogue discusses them in depth in order to argue in favor of the vice president as the ideal person for this role.

Although the narratives were crafted with the aid of primary sources, such as diaries and interviews, they rely heavily on secondary sources (described in the bibliographical notes). Also, in an effort to weave seamless narratives or to structure a scene, some liberties have been taken. The reader will recognize these instances by the use of such qualifying words and phrases as might have and may.

THE SHAPE OF THINGS TO COME

Washington is often described by historians as the Hidden Hand President for how often he used others to execute his agenda. It may have been Washingtons hand behind the scenes, but more often than not the fingerprints left behind belonged to Hamilton. (Painting of George Washington by Gilbert Stuart; painting of Alexander Hamilton by John Trumbull)

Very few who are not philosophical Spectators can realize the difficulty and delicate part which a man in my situation has to actI walk on untrodden ground. There is scarcely any part of my conduct which may not hereafter be drawn into precedent.

President George Washington

On New Years Eve, 1793, as Americans lifted their glasses in joyous celebration of the coming year, Alexander Hamilton was imagining himself in another line of work. He had been at George Washingtons side, on and off, since he was in his early twenties, and now, facing middle age, he was considering a life without him. For a man of Hamiltons mind and abilities, the future was limitless. He might run for governor of New York or for the US Senate or even for the presidency. But first, he would need to resign his post as treasury secretary and reestablish himself as a private citizen. Taking his glass in hand, Hamilton greeted the new year happily, secure in the thought that this year he might finally be able to free himself of Washington and move on. To his great disappointment, he soon discovered his plans to leave were a bit premature.

In 1794, the worlds two superpowers, Great Britain and France, went to war, forcing the United States to choose a side. Hoping to avoid inflaming tensions with the British that had been festering since the end of the Revolution, President Washington favored neutrality. But the British were not going to make it easy for him. They had acquired an annoying and dangerous new habit. To cut off French supply lines in the West Indies, the British forced into the nearest English port any American merchant vessel engaged in commerce there. The ship was emptied of its cargo, and its crew members were given the choice of joining the Royal Navy or finding their own way home.

Washington envisioned a treaty with the British that would keep America neutral while also giving American merchants the freedom to continue trading with the French. But a huge swath of the American public opposed his efforts. Accusing the legendary war hero of being unpatriotic for wanting to pursue a peace treaty with a nation still widely regarded as the enemy, some longtime defenders of the president began to wonder aloud whether Mount Vernon was not a more fitting place for the aging president to spend his autumn years.

Further complicating matters, Washington faced this crisis without the help of his secretary of state Edmund Randolph, who was dealing with a crisis of his own--having recently been accused of treason. Randolph was not his first choice to lead the State Department, but Washington could find no one else willing to replace Thomas Jefferson when he resigned the previous year. A few poorly chosen words by Randolph, to the French ambassador did permanent damage to his relationship with the president. So, when he needed Randolph most, Washington had to look elsewhere for someone to shepherd his treaty with Great Britain. As he so often did in difficult times, he turned to Alexander Hamilton.