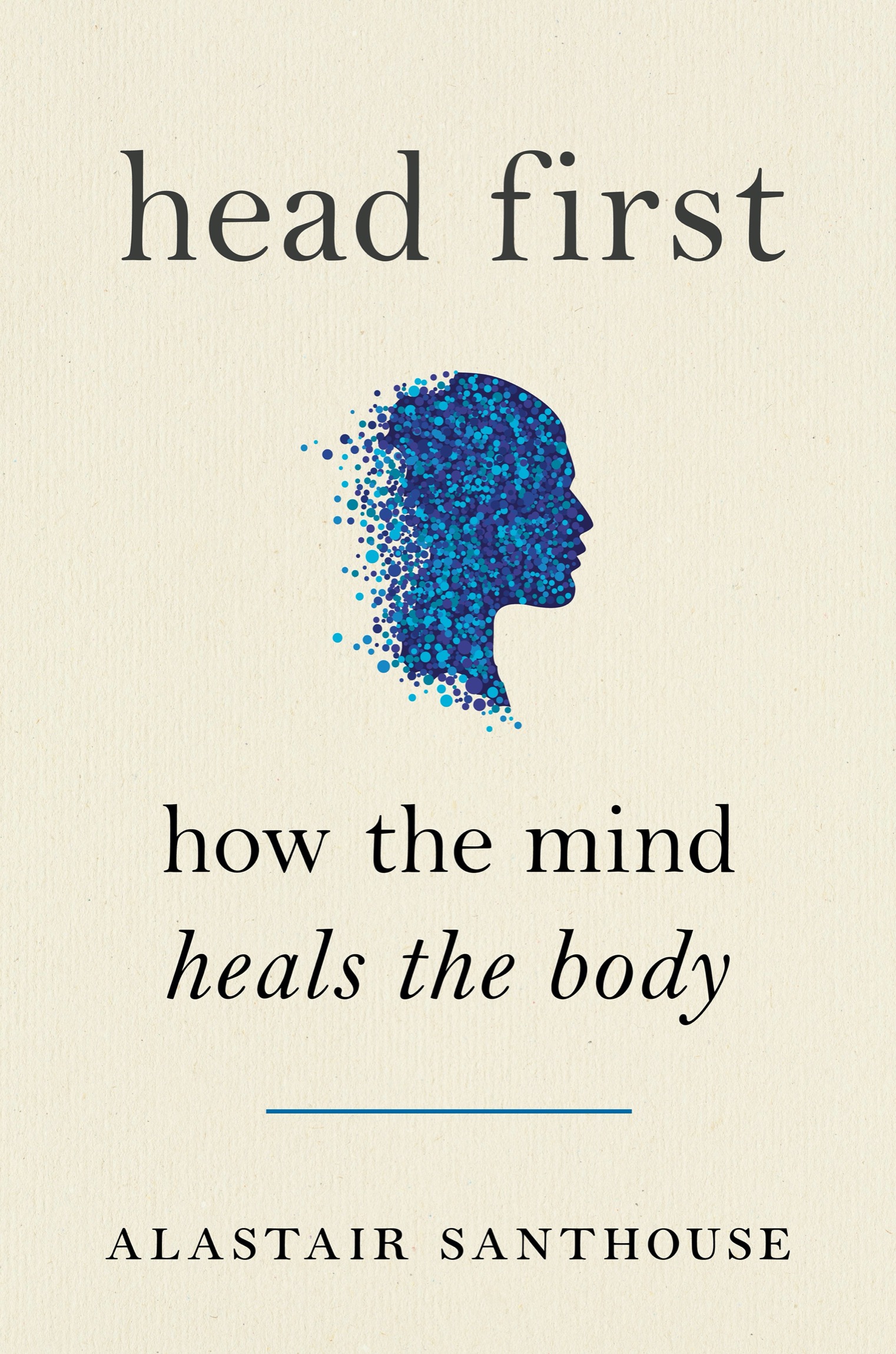

Alastair Santhouse - Head First: Its All in Your Head: How the Mind Heals the Body

Here you can read online Alastair Santhouse - Head First: Its All in Your Head: How the Mind Heals the Body full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2021, publisher: Avery Penguin Random House LLC, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Head First: Its All in Your Head: How the Mind Heals the Body

- Author:

- Publisher:Avery Penguin Random House LLC

- Genre:

- Year:2021

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Head First: Its All in Your Head: How the Mind Heals the Body: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Head First: Its All in Your Head: How the Mind Heals the Body" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Head First: Its All in Your Head: How the Mind Heals the Body — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Head First: Its All in Your Head: How the Mind Heals the Body" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

penguinrandomhouse.com

Copyright 2021 by Alastair Santhouse

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Santhouse, Alastair, author.

Title: Head first: how the mind heals the body / by Alastair Santhouse.

Description: New York: Avery, Penguin Random House LLC, [2021] | Includes index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2020042327 (print) | LCCN 2020042328 (ebook) | ISBN 9780593188750 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780593188767 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Mental health servicesEvaluationGreat Britain. | PsychiatryGreat Britain. | PsychiatristsGreat Britain.

Classification: LCC RA790.7.G7 S26 2021 (print) | LCC RA790.7.G7 (ebook) | DDC 362.20941dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020042327

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2020042328

Book design by Laura K. Corless, adapted for ebook by Maggie Hunt

Neither the publisher nor the author is engaged in rendering professional advice or services to the individual reader. The ideas, procedures, and suggestions contained in this book are not intended as a substitute for consulting with your physician. All matters regarding your health require medical supervision. Neither the author nor the publisher shall be liable or responsible for any loss or damage allegedly arising from any information or suggestion in this book.

The stories chronicled in this book are based on many years of practice. However, maintaining patient confidentiality is of utmost importance, so the author has taken care to remove any identifying clinical or personal information. Some of the case studies are an amalgam of several patients.

pid_prh_5.7.1_c0_r0

For Sara and the Boys

ASK NOT WHAT DISEASE THE PERSON HAS, BUT RATHER WHAT PERSON THE DISEASE HAS.

SIR WILLIAM OSLER, 18491919

I remember Roland well, although I met him only twice. In fact, I heard him before I saw him; I was startled by an alarming noise, somewhere between a cough and a snort, as I approached the waiting room on my return from lunch to start an afternoon clinic.

I sat down with him in my consulting room, and he told me his story. Age thirty-three, he was from Gabon, unmarried, and had come to the UK three years earlier. Since his arrival he had experienced increasing discomfort with his throat, resulting in frequent explosive exhalations. His regular doctor had been unable to make a diagnosis and had rather unusually, rather than referring him to a single specialist for an opinion, made three separate referrals.

Roland had found life in the UK difficult. He had struggled to find work, had no family here, and was unable to see his daughter, who lived with an ex-partner in Gabon. His symptoms had begun several years before and were now worse than ever. As he snorted and spluttered, I found myself distracted by a persistent urge to clean my desk with an antiseptic wipe. It was with some difficulty that I listened to his story. He had been encouraged by friends to see his doctor, who, reading between the lines, hadnt initially worried about his symptoms but had subsequently referred him to the hospital for more opinions.

It was clear to me that the cumulative stress and disappointment in Rolands life had exacerbated a nervous tic, which was now so deeply ingrained in his motor system as to be automatic. I had seen symptoms like this before, in which unusual movements and behaviors, rehearsed often enough, become hardwired. For example, I have seen people present with a strange gait that makes walking unnatural and effortful, seemingly without any deliberate simulation, even when there is nothing wrong with their muscles or nerves. Sometimes patients experience persistent pain or dizziness or can speak only in a whisper, without there being any identifiable physiological cause, even after months or years of medical investigations. The ways in which patients present are as plentiful as the number of symptoms.

When I treat such patients, I acknowledge that these illnesses, even if they have no clear-cut physical cause, are not made up or simulated; they are as real as any other illness, even if their cause is believed to be psychological.

It is difficult to know why an individual will have a particular symptomfor instance, paralysis rather than dizziness or speaking in a whisper. Back in the early 1900s, some psychiatrists believed that an individuals symptoms carried a symbolic significance. For example, someone who witnessed an appalling event might develop blindness. Although this sort of belief is still occasionally mentioned in psychiatry textbooks, not many people believe it.

In Rolands case, his symptoms began with a cough and a sore throat, but his persistent focus on his breathing developed into a preoccupation. His cousin told him that he must have been cursed, an idea that Roland felt was being fulfilled in the shape of serious illness. This worry served only to perpetuate his symptoms, until coughing and exhaling noisily through his nose was as natural to him as breathing. Such presentations are often known as conversion disorders, referring to the theory that psychological stresses are converted into physical symptoms, although it should be acknowledged that there is little consensus on what such presentations should be called. Our disorganized classification system is a reflection of the different ways in which people have understood these symptoms over the years. Some diagnoses, such as conversion disorder, stem from the theory of Freudian psychoanalysis, while other diagnoses, such as persistent physical symptoms, are descriptive, yet both might be talking about the same thing. The term functional disorder is commonly used to indicate that while the structures of the bodythe nerves, muscles, and organsare all intact, their function is impaired. Sometimes the terms used are pejorative or insulting (a heart-sink patient, referring to the effect they have on a doctors morale; a fat folder, used to describe the thickness of a patients notes), and yet others such as supratentorial (pointing to a region of the brain), while respectful and medical-sounding, suggest that the cause lies in the brain and are a wink to fellow professionals that the doctor thinks it is all psychiatric.

As I dictated my letter to Rolands GP, I picked up his file and two letters fell out. The first was from an ear, nose, and throat (ENT) specialist, who had diagnosed a problem with his vocal cords. The second was from a neurologist, who had diagnosed a disorder of the nervous system. I began to worry. Had I completely misread the situation? I wondered whether to commit my diagnosis to the notes, my confidence in it steadily waning. I knew the ENT and neurology consultants to be sharp and capable doctors, not the sort who were casual about diagnoses. My diagnosis seemed even less sound when Roland came back to see me some weeks later, smiling and relieved that his symptoms had all but gone. It turned out that, lacking any confidence in his trio of physicians, he had laid out all his cares to a sympathetic priest, who agreed with him that he must have been cursed and administered holy water, thereby effecting this miraculous cure.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Head First: Its All in Your Head: How the Mind Heals the Body»

Look at similar books to Head First: Its All in Your Head: How the Mind Heals the Body. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Head First: Its All in Your Head: How the Mind Heals the Body and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.