INTRODUCTION

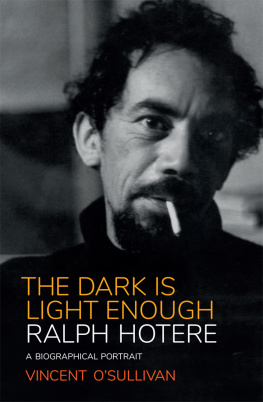

AT A BOOK LAUNCH IN CHRISTCHURCH in 2004, A MESSAGE WAS passed on to me that Ralph Hotere, who had suffered a stroke some time before, would like to talk to me if I was down his way in Port Chalmers.

Ralph at this time was widely regarded as his countrys most significant living artist. We had known each other when he was in London in 1962, on a scholarship to the Central School of Art. We saw each other again when he returned to Auckland, then while I was living in Cambridge and he was working on his huge mural for the Hamilton Founders Theatre. After that, we met intermittently once he had settled in Dunedin.

Few men needed fewer words than Ralph Hotere. There are few things I can say about my work that are better than saying nothing, he once famously said. When I called on him at Port Chalmers, he had recently seen my biography of John Mulgan, the scholar, soldier, and author of the classic New Zealand novel Man Alone. He wondered if I would be interested in writing his own life story. I mentioned a couple of reasons why I might not be the person to do it, being Pkeh and an outsider to the art world. He saw no problem with that, and I accepted.

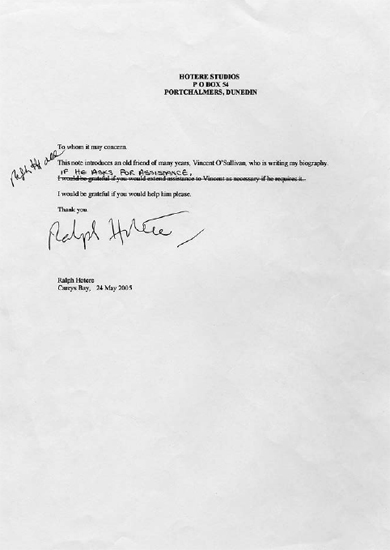

As we had known each other for so long, it did not occur to either of us to put our agreement in writing it was a trusted partnership between friends and artists, like so many of Ralphs collaborations. He said I might write anything that I thought relevant about him, and use any of his works to accompany the text. He helped and encouraged me to make contact with a wide range of family, friends and acquaintances without restriction or veto, giving me a note to use that read: This introduces an old friend of many years, who is writing my biography. If he asks for assistance, I would be grateful if you would help him please. It was dated May 2005. He gave me free access to his personal papers and I visited him frequently at his home above Careys Bay in the several years that followed, where we talked widely if sparingly over his life and his interests. His Mitimiti whnau was marvellously helpful, as were the numerous friends and fellow artists I spoke with, as the lines of his life were filled in. What struck me most, perhaps, was how extensive and warm Hoteres friendships were, across the spectrum of New Zealand life.

For a number of reasons, what Ralph and I had started was brought gradually to a halt. It became more difficult to have private conversations with him, and then not possible at all. It was through Ralphs sisters that I received his message to keep on with the book, when I was no longer able to see him. I continued the story as far as we had got together up to his seventies and put aside the draft of what I had done. That draft has become this book.

It may seem strange to publish an incomplete life of an artist, and without images of his work. Necessarily, I see what I have written as an incomplete portrait, rather than the more desired account of one of this countrys great artists and compelling personalities. Future scholarship will attend to so much more. But as Ralph himself asked me to write on him, and I assured him I would do so, it now seems a personal debt I owe to him, and to his constantly encouraging whnau.

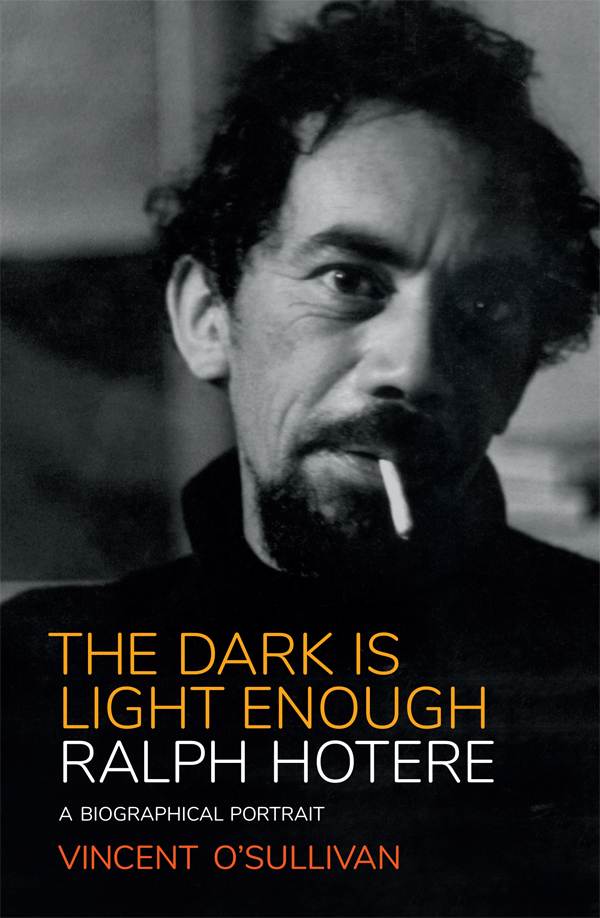

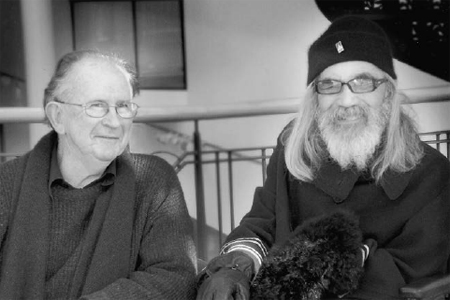

Vincent OSullivan and Ralph Hotere in 2006. REG GRAHAM.

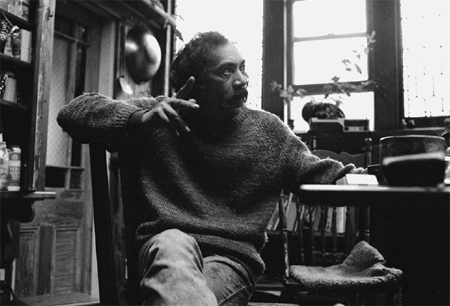

The Mitimiti cemetery overlooking Hto Hemi. LIZ LIGHT.

I

A PLACE ALWAYS ONES OWN

THE STORY THE HOTERE WHNAU TELLS OF THEIR PARENTS MEETING is like pages from a romance. There was a girl from Kaihu called Ana Maria Taniere, who was pretty and hardworking and kind, and left school when she was twelve. Her Ngti Whtua family was strict, and expected a lot of her. Her father was a katekita, a lay person in a Catholic parish who would lead prayers and instruct in the faith, as the priest visited the small, remote church perhaps once a month. He would live to be one hundred years old. His daughter was washing clothes in a creek when a handsome young man from Te Kao, five years older than herself, who was Te Aupuri as well as affiliated with Ngti Kahu and Ngpuhi, rode by and talked with her. He hoisted her up on his horse, and they at once were in love.

Ana was fifteen, and Tangirau Hotere twenty, when they married at St Agnes Church in Te Kao in 1918. The marriage certificate recorded the brides occupation as domestic duties, her husbands as labourer. At first they went off digging kauri gum together. When they decided to settle at Mitimiti, which was Te Rarawa country, it was because Tangiraus father had land there they could farm. Both he and Ana had Rarawa and other iwi affiliations in the Muruwhenua, that large geographical expanse of the Far North, but Tangiraus loyalties were insistently Te Aupuri, an emphasis he passed on to his tamariki. But another strong incentive for where the young couple chose to live was that the small settlement on the coast twenty miles north of the Hokianga harbour if you moved along the beach, but hours if you went by road to Rawene, crossed by ferry to Kohukohu, then drove on through Panguru was Catholic. Mitimiti would be their home for the rest of their lives, and where they would raise their children.