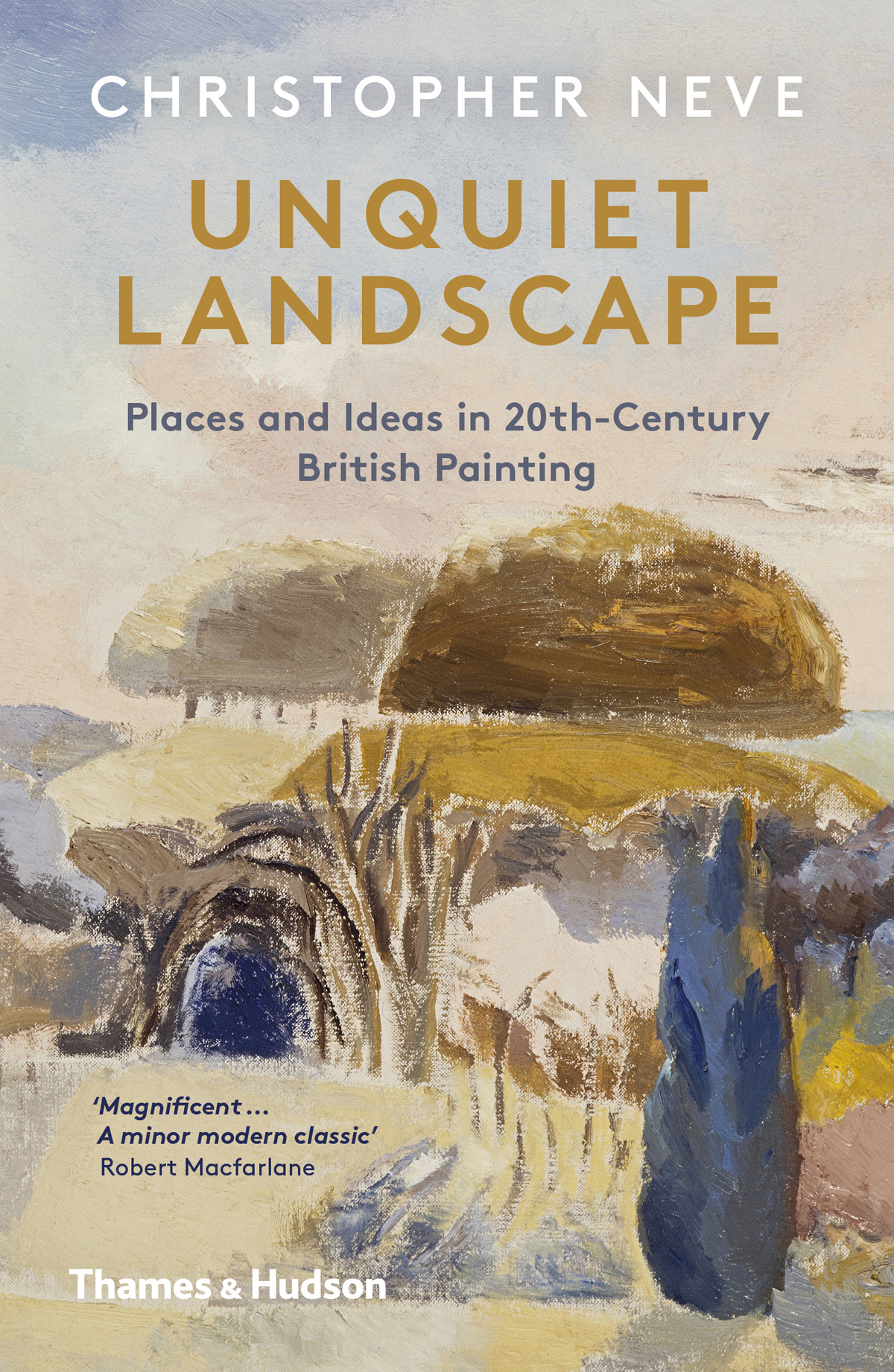

It is that rare thing, a modern vade mecum.

Observer

He has a painters knowledge of means and a poets insight into aims.

Literary Review

He is one of a rare breed, a painter who can express himself in words. He is never obvious and sometimes difficult.

Sunday Times

Very occasionally you encounter a writer who creates a work of art while writing about them The authors ability to articulate what many of us have incoherently felt comes over triumphantly on every page. He comes as close to anyone to bridging the gap between pictures and words; he is part topographer, part painter, part poet and part psychologist. All who have an interest in English art should read Unquiet Landscape and then look at the pictures.

The Tablet

The book is an object lesson in how to see. His chapter on the relationship between seeing and feeling is the best modern exploration of the subject I know. He is especially sensitive to the work of visionary painters, and his chapters on these are the finest in the book.

What immediately strikes one on reading the opening paragraph is the force of his personality and of his opinions. Unlike academic criticism, this is a book written by a human being. The privilege of seeing with a man who gives so much of himself to the act of attention.

The Green Book

A finely written book, almost Proustian in its search for the exact phrase.

Historic Houses

About the Author

Christopher Neve is a painter and one of the leading experts on British art of the 20th century. He has written several books and numerous articles.

In addition to a new preface, this edition features expanded content on the artist Sheila Fell. For copyright reasons, the plate section has been removed from this digital edition.

Other titles of interest published by

Thames & Hudson include:

John Nash

Andy Friend, with a foreword by David Dimbleby

Ravilious & Co

Andy Friend, with an introduction by Alan Powers

Spirit of Place

Susan Owens

History of Pictures

David Hockney and Martin Gayford

Antony Gormley on Sculpture

Antony Gormley

See our websites

www.thamesandhudson.com

www.thamesandhudsonusa.com

CONTENTS

The situation in which this book was written was as follows. I worked in an old-fashioned magazine office in London. A time of galley proofs. This was on the south side of Covent Garden when fruit and vegetables were still traded there. If it was hot, to get out of the office I would ask some artist I admired if I could come and see what he was doing. And if it was wet in winter I would send a postcard to some other artist and take a train to wherever he or she lived and have a conversation with them in their studio or perhaps in their kitchen. I was only required to write an article of between fifteen hundred and two thousand words once a week so this and the visits to artists took up about one third of my week and the rest of the time I spent painting as hard as I could. Because my paintings did not sell very well I also taught at a school where the pupils liked art history and which I could reach on my bicycle. In this way I found it easy and pleasant to get to know a good many artists, most of them much older than me, and sometimes I wrote about them and more often I did not. It was an excellent magazine office where there was a good knowledge of painting and architecture and I had a long-suffering editor and there was always the colourful activity of the fruit and vegetable market outside the window to watch if I could not think of a first paragraph.

When I had got to know many of the artists reasonably well they died, and as I had also come to know the landscapes in which they worked I was sometimes able to write about them and their work at much greater length. But this was several years later.

The oblique ways in which the artists chose to discuss their work were diverse. Quite often music came into the conversation. Ben Nicholson had a number of old 78 jazz records which had been given to him by Mondrian and we listened to these with attention and discussed them. Dutch Swing College Band.

Winifred Nicholsons obsessions being rainbows, prisms and wild flowers, the conversation very often turned to them. She was not above lightening the mood by wearing a hat she had made out of a wicker wastepaper basket with silver milk-bottle tops sewn onto it. Alan Reynolds liked to talk about Debussy and bicycle racing and Paul Klee to avoid mentioning what he was doing. William Townsend spoke of hop-stringing and geometry. Henry Moore showed me mostly bones and shells and his Czanne. Cedric Morris, as well as being very funny, talked mostly about plant collecting and showed me his iris garden in detail. Heather and Robin Tanner talked about botany and lettering and Time. Edward Burra, towards the end of his life, began to swear and use obscene language in order to avoid speaking about any kind of art, especially his own.

Where artists were already dead I had the great good fortune to talk to people who had known them well, for example Peggy Angus, who was still in the cottage in which Eric Ravilious stayed at Firle, and Ronald Blythe in John Nashs farmhouse at Wormingford. And when even their people were absent I could always immerse myself in their landscape while reading their letters or diaries. For this to work I made it a rule always to see every picture I was writing about in the flesh and never, whatever Stanley Spencer had to say on the subject, just to see them in reproduction.

In this way I was eventually able to build up a short book about thought and what it is like to paint, instead of interrupting the pictures, as Ben Nicholson would say, which are dumb anyway, and this seemed to be entirely natural and appropriate. In the process I soon noticed that many artists in conversation came across quite differently from the way in which they came across in their work, and that the most unlikely painters painted with extreme sensibility.

The result may be regarded as fiction but there is an outside chance that it throws some light on fact.

Now that they are spread out on the far slope of reputation, perhaps we can see these people more clearly than I saw them then. Each of them could change your life with wonder and delight by the beauty and originality of their work. And each of them could show you a landscape as if for the first time. That in its way is a glimpse of eternity. It made me happy at the time and still does.

But thirty years ago artists paid little or no attention to explaining themselves and sometimes seemed quite pleased to be offered a plausible account of what they were doing. I suppose they knew that what was communicated by the work could be quite different from what they were putting into it. (Or thought they were putting into it). Or, more likely, their motives were as obscure to them as they were to everybody else.

That is why on the whole we talked of other things and this book is about other things rather than falling into the old art-historical trap of attempting to say what the pictures mean. There was, though, a tacit agreement that talking about something else was the best possible way of saying anything worthwhile about the paintings without including them in the conversation directly. I strongly believe that if you have to say anything at all about pictures this is the best way to do it, though the best way of all is of course to remain silent.

Next page