1. HOW TO APPROACH PAINTING

A lifetime of painting and of teaching has convinced me that there is a general misconception as to what art study really is. Many believe that when they are reading a scientific treatise on some department of painting, or on its history or appreciation, they are studying art. What they are doing is studying the chronological sequences of the great painters lives (which is excellent for the intended lecturer), or else studying a writers report of his emotional responses to great paintings.

The art of painting, properly speaking, cannot be taught, and therefore cannot be learned. Only certain means can be discussed. I believe about art, as I believe about music or architecture, that the only way to study is to practice; and that any good teacher can point out certain intellectual or technical makings, certain helps that will give a fulcrum to the lever of practice.

Consider how little any eulogy, or even any aesthetic treatise, will help the student who first sets up his easel out-of-doors and faces nature, with its changing, fleeting panorama of color, light, movement, sound. How shall he even begin to begin? Out of his pocket bulges a volume: The Influence of Art Upon Society. Or another: Does Art Uplift? Little good will either book perform!

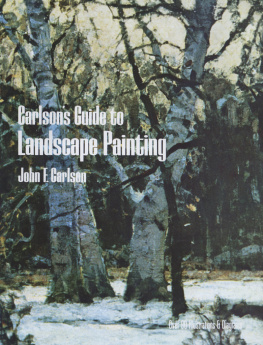

In this book, on the contrary, the endeavor is to present to the student of landscape painting (as well as to the lover of pictures) a few of the logical and therefore teachable aids that must underlie even the most amateurish approach toward achievement in this art, or toward an appreciation of the technical difficulties involved in its creation.

No one can teach art. No one can give a singer a glorious voice, but granting the voice, and emotional sensibility, a teacher can teach a man to sing. In painting, as in singing, there is no excuse for a poor technical performance. We take it for granted that the man who is to give a concert at Carnegie Hall knows how to sing. If he does not, we do not wish to listen to him.

In painting we are apt to be very forgiving of poor technical performance. Why, see! See what the man intended here! In art, intentions have no place; only results. In good art, the results do not have to be explained. As a matter of fact, there is but one kind of art and that is good art. There is no comfortable halfway station; it is either fine, or it is not art.

But art is a thing so much of the imagination, of the soul, that it is difficult to descend to the fundamentals of technique and yet make it plain to the student that these are but the means, and not an end in themselves. The underlying principles, or fundamentals, should be so hidden away by the beauty that they are eventually to support, that it would require much digging to disclose them. These are things we painters knew long ago, and have half forgotten. It is this that causes many teachers to attempt the impossible: that is, to start the student from the place where they, themselves, have arrived!

In this book I have proceeded upon the assumption that my readers have had little or no study, and, beginning with the bare canvas, have tried to isolate and enlarge upon the different departments of landscape painting until the student should have a fair idea of an approach to his task. I have tried to place these departments in useful sequence (according to their importance), taking a chapter for each. I have attempted to create a block or angle theory to help the student simplify, and I have tried to give the reasons for such simplification.

It is the purpose of this book to present to the student certain common sense ideas of procedure, without stifling the enthusiasm that is to carry him on. I want him to realize clearly that these ideas or rules are only beginnings; they are means and I want to warn him against considering them ends. I believe that the grave error committed in our past methods of teaching, and the thing which has caused the present uprisings against what is termed academic training, lies in having concentrated too much on curriculum, and not enough upon the end, which is painting.

We have technically overequipped and overloaded the poor beginner. Sometimes pedantically efficient but sadly uninspired men have been allowed to stifle the young and have turned out craft-ridden automatons. Sometimes the teacher has never made it plain that he was not a god after all, but just a teacher, with human prejudices and idiosyncrasies. We have spent so much time preparing a student that when he was prepared, he was spent. What right has anyone to ask any human being to spend three or four valuable years in the antique class when three or four months would suffice? Three months of study from the block hand, or head, or figure, suffices to give the student a good knowledge of form as expressed in mass chiaroscuro, or light-and-dark, as well as a knowledge of proportion. Instantly then, into the life class, to experience the joy of the living, moving, colorful figure! Out-of-doors, into the fields and woods, into the kaleidoscope of color and light. By and by we can return for quiet study to the antique class, and there find that we are just beginning to see and to understand the things we used to look at and not see.

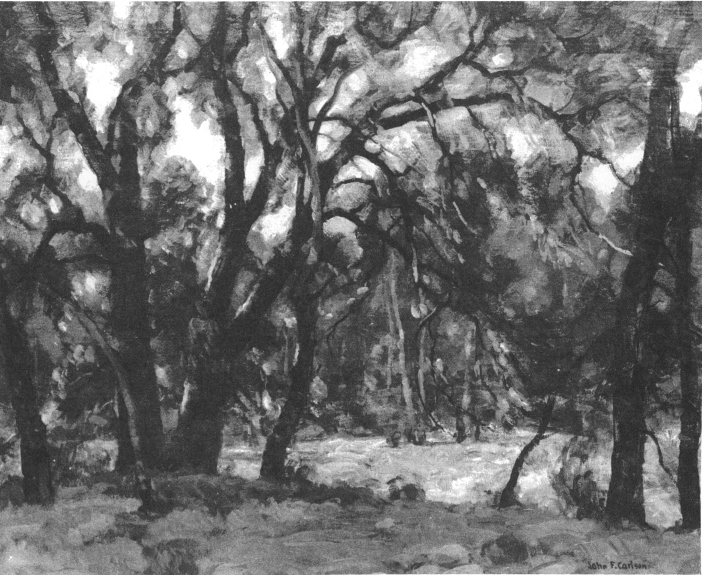

How shall we approach our task of rendering these aesthetic experiences upon canvas so that our brother man may feel them with us? How shall we see nature with a painters eyes, and not merely as a tourist? The word see does not mean, in this instance, mere visual correctness; this never in itself produces a work of art. A snapshot is a correct rendition of physical fact; sharply focused it will show the numberless grasses upon the ground; it can in fact, render these so that we can see nothing else upon the print. The actual form of the mass upon which these grasses occur, it does not suggest; nor does it convey natures subtle color changes or color-flow. But, most of all, the camera does not have an idea about the objects reflected upon its lens. It does not feel anything, and will render one thing as well as another.

This idea, or thrill is the unteachable part of all art. It must be intrinsic in the student. It is presupposed that anyone taking up any of the arts has this inherent sensitiveness to beauty. With this native gift, he can proceed to apply the process of reducing his material to its simplest denomination, eliminating all non-essentials, and leaving only the simplified elements with which to create and express.

By diligent practice with eye and hand (and the logical lobe of the brain), he must master the fingering of the keyboard, as it were, so that technical deficiency at least will not stand between him and expression. Once this is mastered he can very well afford to forget the fingering and proceed to play Chopin or Wagner. When one has thus arrived at the point where he can play, let him not mistake this ability or dexterity for the end or final expression. Let me reiterate, it is only the means to an end.

Study direct from nature. Study to feel, and to know something of her visible functionings. Nature, to the thoughtful, will always remain a vast and delightful storehouse, the fountain of inspiration. Nature is forever providing for the artist untabulated surprises; it is for these that he is to be envied. It is the artists privilege and prerogative to capture these miracles and to transmute them into an expressive form.

Let the student realize at once that there is no method or style through which he can become a fine painter. Have not a care about putting the paint on. Put it on any way you wish, even using the thumb, if you like, so long as you will try to do the thing I shall ask of you. You will be surprised at your own style in the course of a few months. It will be unlike anything you ever dreamed of.