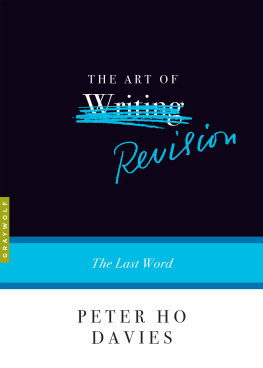

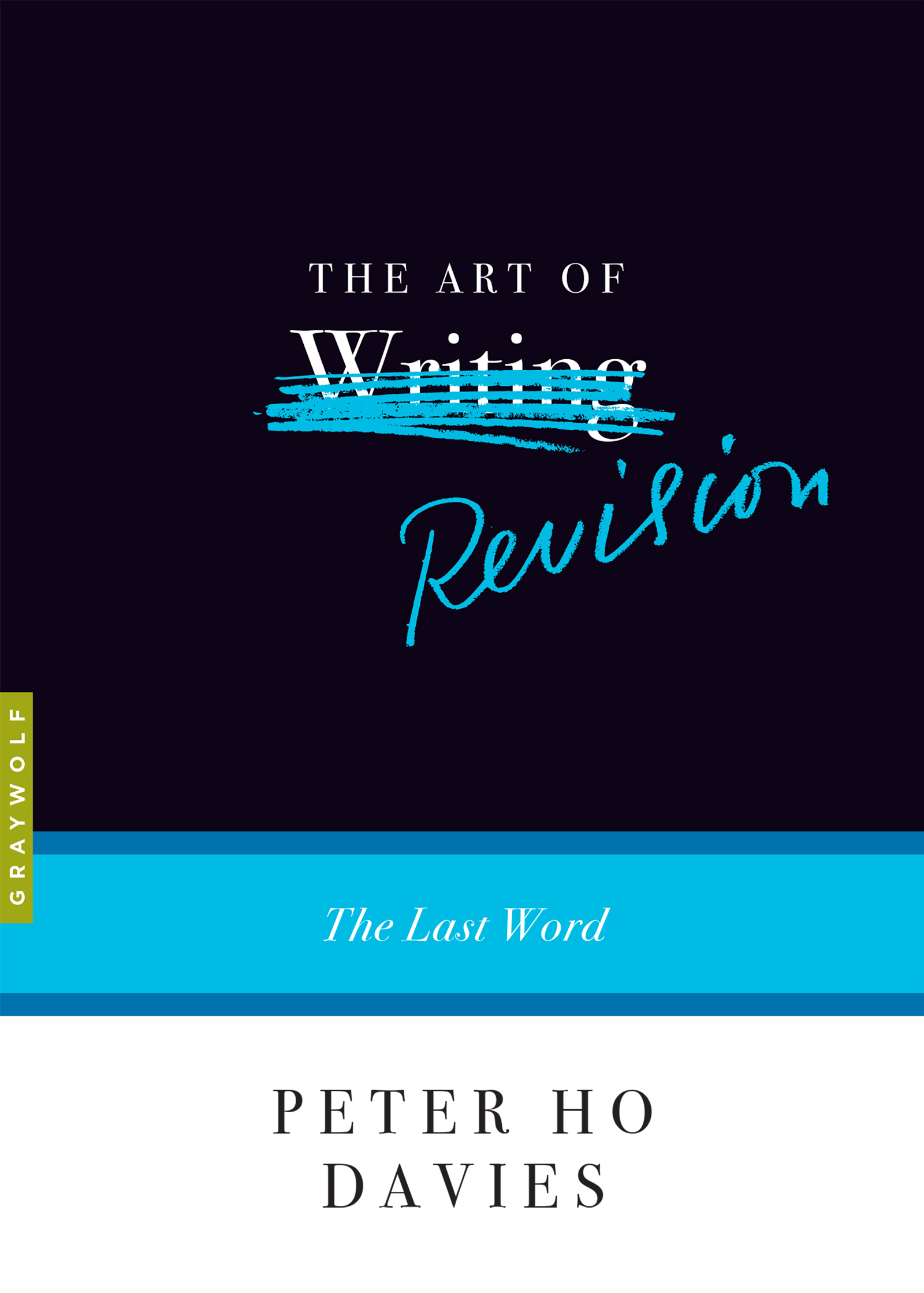

The Art of

REVISION

THE LAST WORD

Peter Ho Davies

Graywolf Press

Copyright ; 2021 by Peter Ho Davies

The author and Graywolf Press have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify Graywolf Press at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

I Remember, I Remember from The Less Deceived by Philip Larkin used with permission from Faber and Faber Ltd.

This publication is made possible, in part, by the voters of Minnesota through a Minnesota State Arts Board Operating Support grant, thanks to a legislative appropriation from the arts and cultural heritage fund. Significant support has also been provided by Target Foundation, the McKnight Foundation, the Lannan Foundation, the Amazon Literary Partnership, and other generous contributions from foundations, corporations, and individuals. To these organizations and individuals we offer our heartfelt thanks.

Published by Graywolf Press

250 Third Avenue North, Suite 600

Minneapolis, Minnesota 55401

All rights reserved.

www.graywolfpress.org

Published in the United States of America

ISBN 978-1-64445-039-0

Ebook ISBN 978-1-64445-134-2

2 4 6 8 9 7 5 3 1

First Graywolf Printing, 2021

Library of Congress Control Number: 2020951356

Cover design: Scott Sorenson

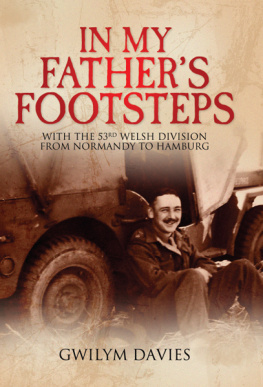

For

Thomas Einion Davies

19342018

You know what question really drives me insane and it happens every goddamned time: How do you know when its finished?

Well, sometimes its hard to tell

Shes talking about a Jackson Pollock we saw at a gallery.

Yeah. Why not three splatters less, or two more?

Thats what makes Pollock Pollock, right? He can just stare at it and say: Thats it. Its complete. Its finished. Thats what makes you an artist.

Billions, season 5, episode 7: The Limitless Shit

by Emily Hornsby, Brian Koppelman, and David Levien

THE ART OF REVISION

THE LAST WORD

Prologue: A Study of Provincial Life

Here is a story: it happens to be true.

In 1979, when I was twelve or thirteenaround the same age as my own son as I write thisI witnessed an act of heroism on my fathers part. Not everyday heroism of the working-a-job-he-hated-to-support-his-family variety, or the faithful-to-his-wife-for-fifty-years variety, or even the regular-visits-to-his-aged-mother-in-a-nursing-home variety (though he practiced all of those, too), but old-school, stand-up, risking-physical-harm-for-the-sake-of-another heroism.

This was in my hometown of Coventry, Englandthe model for George Eliots Middlemarch ; Im borrowing her subtitle for this vignettea Saturday morning on a busy downtown shopping street. Through the crowds we saw a boya teenager, maybe sixteen or seventeenrunning toward us. We probably heard him first, his footsteps echoing off the concrete and plate glass. Except he wasnt just running, I thought, he was running a race. Leading three or four others. Except they werent racing him, I realized, they were chasing him. And they were skinheads. And he was wearing a turban. This at a time when the far-right National Front was resurgent in Britain.

But even as I registered these details, I couldnt make sense of them in the moment, clinging to my first impression that it might all have been some lark, teenage high jinks. Even when the chasers caught up with the chased, knocked him down, put the boot in, I dont think I fully understood what was happening. Nor, Im sure, did the other shoppers around us. I like to think they didnt intervene, not out of fear for themselvesthere was no time for that rationalizationbut out of simple shock and incomprehension.

In fact, my father was the only one to go to that boys aid, pushing and pulling the attackers off him. Luckily, as bullies will, they ran off as soon as confronted. Luckily, their victim wasnt too badly injured, physically at least. After picking himself up and dusting himself off he thanked my father, but refused further help (in the quintessentially British form of the offer of a cup of tea) and hastily limped off in the other direction.

The whole thing took less than five minutes. The crowd of Saturday shoppers began to flow again, and after a moment my father and I merged with it. I dont even recall much talking about the incident with him. But Ive never forgotten it.

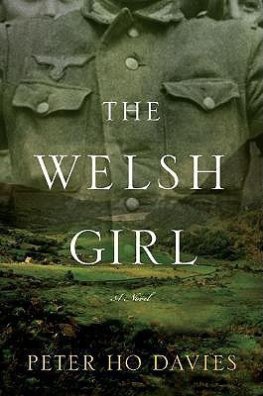

Here is a revision of that story, a version of it that I told near the start of my 2007 novel, The Welsh Girl , transposed to 1930s Germany and told from the point of view of a German Jew, called Rotheram (the Anglicized version of Roth that he eventually adopts), grappling with the decision to emigrate:

Hed been dead set against leaving, even after seeing a fellow beaten in the street. It had happened so fast: the slap of running feet, a man rounding the corner, hand on his hat, chased by three others. Rotheram had no idea what was going on even as the boots went in, and then it was over, the thugs charging off, their victim curled on the wet cobbles. It was a busy street and no one moved, just watched the man roll onto one knee, pause for a moment, taking stock of his injuries, then pull himself to his feet and limp hurriedly away, not looking at any of them. As if ashamed , Rotheram thought. Hed barely realized what was happening, yet he felt as if hed failed. Not a test of courage, not that, he told himself, but a test of comprehension. He felt stupid standing there gawking like all the rest. Too slow on the uptake to have time to fear for himself. When he told his mother, she clutched his hand and made him promise not to get involved in such things. He shook her off in disgust, repeated that he hadnt been afraid, but she told him sharply, You should have been.