The Family Crisis as a Public Event

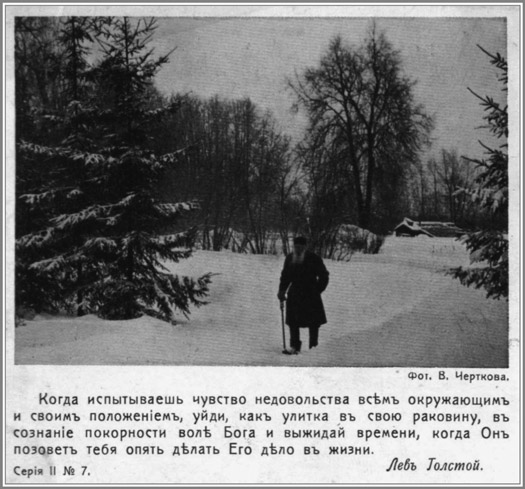

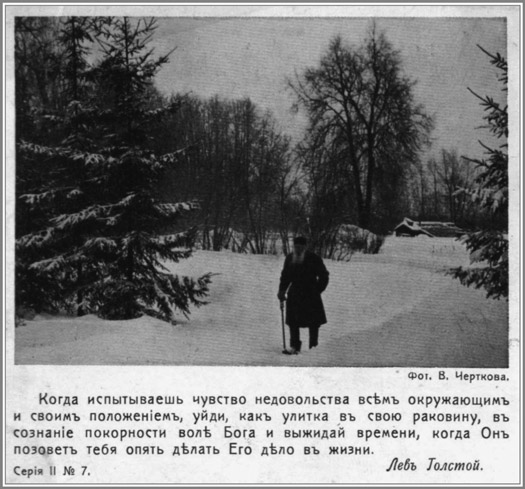

One of a series of postcards produced by Vladimir Chertkov featuring photographs and proverbs of Tolstoy. This one reads: When you feel dissatisfaction with your surroundings and your situation, go away, like a snail into its shell, conscious of your submission to the will of God, and wait for that time when he will again call you to do his work in life.

And every one that hath forsaken houses, or brethren, or sisters, or father, or mother, or wife, or children, or lands, for My Names sake, shall receive an hundredfold, and inherit everlasting life.

ST. MATTHEW 19:20

Though buffeted on the eve of World War I by heavy seas, the family ship did not go down. Yet many who abandoned ship did so with relief, with a sense of deliverance, and with the hope of embarking on a personal adventure, only to end in horror.

MICHELLE PERROT

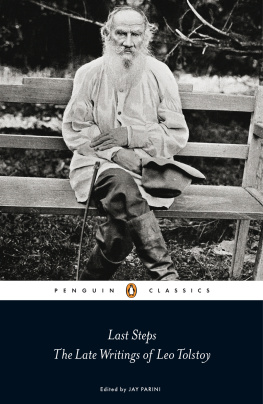

When Lev Tolstoy left his house in October 1910, he had no destination in mind. His immediate objective was to go somewhere where he would not be found for a few days, then to head further into the great world, as he called it. At the nearby railway station he purchased tickets for two different destinations, hoping to cover his tracks. He had arranged to keep his daughter Aleksandra informed of his journey, on condition that she tell no one else where he was, and had told her that any telegrams received from him would be signed not with his real name, but with Nikolaev. Thus Tolstoy set forth into the public domain, casting off his famous name to take on one more befitting the vagrant life he imagined.

A popular Russian legend holds that in 1825 Tsar Alexander I abandoned the throne to become a monk in the depths of Siberia, adopting the name Fyodor Kuzmich. If Tolstoy ever imagined that he could accomplish something similar, he was confronted instead with the realities of the early twentieth century: a long inquiry into his personal life and a public examination of who he was in the most quotidian sense. When the public set out to find Tolstoy after he left his home, they were not only looking for him physically, but were also searching for his identity. Much of this search focused on the Yasnaya Polyana he had left, where, it was believed, the secrets of his home life would reveal the motivations for his actions. Family members, servants, friends, and visitors were interviewed in the hope that they might provide inside information to explain what had happened. When those closest to the events began providing conflicting information, however, it became clear that the private self that was sought had long ago been lost in the morass of Tolstoys overgrown persona, even in his own home.

If literature was a second government in Russia, as it has aptly been described, Tolstoy was without question its tsar in the early twentieth century. He made much of his discomfort with this role, but it did not stop him from also becoming the patriarch of a secular church. Tolstoyanism was part of a tremendous industry built around his writing, but it extended far beyond literary celebrity and came to refer to a whole lifeway that found adherents from the 1880s well into the twentieth century. The namesake of this movement had renounced his wealth and privilege to become an ardent moralist, advocating pacificism, vegetarianism, nonviolence, and menial labor, and these views were soon adopted by followers around the globe, many of whom organized communes where they lived on the land and shared their labor. The movement spread throughout the world, including Japan, India, Bulgaria, Canada, and the United States. In Russia it became a significant cultural and political force, producing vegetarian kitchens in major cities and communes throughout the country.

Tolstoy was eminently aware of the pitfalls of having a movement named after him and was quick to tell people that he was not himself a Tolstoyan. But he also knew very well that many of his actions, including his departure, were deeply Tolstoyan gestures and would be interpreted that way by the public. His wife was convinced that most everything he did was Tolstoyan and that she had long ago lost the Lyova she had married.

Tolstoy admitted that he felt he had lost himself in the process as well, and comments in his diary after his departure suggest that he too was searching for that same real self, which he did not believe he could find at home. Much of his writing over his last years describes a longing for an unmediated, authentic self that could act outside of his own history and representation. His attempted escape would not readily lend itself to this process, however: Tolstoy ventured into the great world as a modern celebrity, and his departure only further stimulated the newspapers to narrate. This was a familiar dynamic for all involved. Tolstoys plowing and bootmaking may have been sincere attempts to ethically center himself in everyday activity, but he knew very well that they had also come to serve as archetypal gestures suitable for quick caricatures of his moral persona. His departure could be read as a closing bow to his audience; as he set forth to walk the walk in his homemade boots, he stepped in the long shadow of his representation, along a path already marked by his persona.

Another postcard featuring images of Tolstoys peasant ways. Ilya Repin, two of whose images are shown here to the right, contributed much to this iconography.

The public search for the real Tolstoy was in fact stimulated by this persona, and it continued, and even intensified, after his death. Family diaries and private letters were quickly published, offering what for that time were considered shocking intrusions into the realm of the private. The public laid claim to these materials as if by eminent domain and found itself arbitrating the family dispute over Tolstoys legacy. The family acknowledged this authority by producing open letters for the newspapers discussing the execution of his willappealing to the public to take their part in a rancorous dispute over Tolstoys papers. The documents that they produced as evidence, however, are marked by such a long-standing anticipation of this intrusion that they can scarcely be read as private papersparticularly where they touch on the issues most relevant to Tolstoys departure and legacy. Deciding how to best honor Tolstoys will became an exercise in the hermeneutics of these documentsof determining how they could best yield the information (legal, but also spiritual and psychological) necessary to come to appropriate terms with his legacy. The Russian public found itself orienting not only to the traditionally legitimate claims of blood relations but also to others that were complex and ill-defined, including its own significant interest in the matter. Some wanted nothing of a heritage that denied the patriarchal rights of the family, while others celebrated the bestowal of his gifts on the family of man. This chapter describes how Tolstoys estate was divided among these public and private allegiances.

News of Tolstoys departure turned the attention of the startled public first on Yasnaya Polyana. The great writer of the Russian land had abandoned one of the most fabled estates in all Russia, plunging his family, and his wife of forty-eight years, into crisis. Speculation over what might have inspired his sudden and secret departure centered on family issueshad there been a decisive argument, perhaps over Tolstoys refusal to accept the Nobel Peace Prize, or to accept one million rubles for the rights to publish his collected works? This curiosity was piqued by further sensational reports: Sofia Andreevna had responded to her husbands farewell note with dramatic resolve, attempting suicide by twice running from the house and throwing herself into a pond, then declaring her intention to starve herself to death. Reporters were soon snooping around Yasnaya Polyana for clues, and the newspapers were filled with pictures and drawings of the estate, as well as photos of family members and other principal characters. The family members resisted this attention at first, but after two days of closed consultation they realized that their story would be told with or without their participation and decided to release a statement to the press. They recognized that they themselves were in the spotlight, and came to understand their own stake in the representation of the events that were transpiring. On October 31, Andrei L'vovich made an announcement to a reporter for Novoe vremia, initiating what was to become a long public airing of the family linens: This sad occurrence shook our whole family. This is an entirely intimate matter, not suitable for discussion in the press, but unexpectedly for us in the Moscow and Tula papers there appeared descriptions of our family grief, and moreover in a sensational tone, and thus I decided to relate everything I know so that correct information about what has happened at Yasnaya Polyana might appear in Novoe vremia.