All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Random House, an imprint and division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Random House and the House colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Names: Greenhouse, Linda, author.

Title: Justice on the brink : the death of Ruth Bader Ginsburg, the rise of Amy Coney Barrett, and twelve months that transformed the Supreme Court / Linda Greenhouse.

Description: New York, N.Y. : Random House, 2021. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021013364 (print) | LCCN 2021013365 (ebook) | ISBN 9780593447932 (hardcover) | ISBN 9780593447956 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH : United States. Supreme CourtHistory. | JudgesSelection and appointmentUnited States. | Ginsburg, Ruth Bader | Barrett, Amy Coney. | Political questions and judicial powerUnited States.

Classification: LCC KF 8742 . G 743 2021 (print) | LCC KF 8742 (ebook) | DDC 347.73/26090512dc23

PROLOGUE

THE CHOSEN ONE

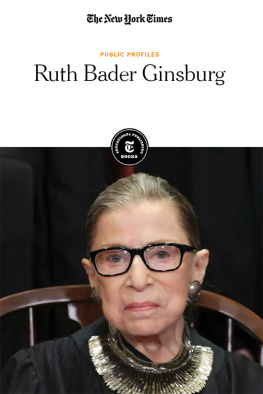

T he late October sky had grown dark, but the lights aimed at the White House were so bright that on the Truman Balcony it might have been high noon. She stood bathed in the glow, the president of the United States by her side, he bundled in a heavy coat against the evening chill and she in a short-sleeved black dress that brushed the top of her knees. Her light brown hair fell straight to her shoulders. She looked younger than her forty-eight years. Barely an hour earlier, by a near party-line vote of 52 to 48 (with all Republican senators except Susan Collins of Maine voting in favor and all the Democrats voting against), the Senate had confirmed her to a Supreme Court seat that had been empty for the mere five weeks since the death of the woman who had occupied it for twenty-seven years, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg.

Not for 151 years had the Senate confirmed a Supreme Court nominee without a single vote from the minority party. For the Democratic senators, who had refused on principle to show up for the Judiciary Committee vote, filling a Supreme Court vacancy on the very eve of a presidential election was an illegitimate exercise of power. But to Senator Mitch McConnell, Republican of Kentucky, the majority leader who during the past four years had shepherded more than two hundred of President Donald Trumps nominees to their life-tenured seats on the federal bench, it was the reason he was there.

Moments before climbing the stairs to the balcony, the newly confirmed nominee had stood on the South Portico of the White House in front of two hundred invited guests seated on the South Lawn. Her husband held a Bible as Justice Clarence Thomas administered the Constitutional Oath, required of all federal officials. She had chosen the courts most outspoken conservative, its only Black member, for this special honor. No other Supreme Court justices were present. In addition to the Constitutional Oath, federal judges also take the Judicial Oath, in which they promise to do equal right to the poor and to the rich. Chief Justice John Roberts would administer that oath the next day in a discreet ceremony at the Supreme Court.

But there was nothing discreet about this night. The election was eight days away. In many states, voting was already under way, and some ten million Americans had already cast their ballot for president. The Truman Balcony tableau, Democrats would grumble the next morning, was the ultimate photo op, breathtaking in its audacity; the country had never seen anything like it. True enough. But on the other hand, was it really so astonishing? The country was witnessing something new, yes. But what was really on display was the culmination of a project launched years before, one that had been set on a path carefully planned, tended, and laid out for all to seeexcept, of course, that most people werent looking, or, if they were, they mistook occasional setbacks for lasting defeat. It was a project to take back the Supreme Court, and the woman on the balcony was its instrument. She was Amy Coney Barrett, the chosen one.

There are few inevitable events in politics, but in retrospect its tempting to see Amy Barretts nomination to the Supreme Court as one of them. Long before President Trumps announcement of her selection in the White House Rose Garden on September 26the celebratory event that became a notorious COVID-19 superspreaderhe had made it clear that he would name her to the Supreme Court if he got the chance. When Justice Anthony Kennedy retired two years earlier, Judge Barrett, who had taken her seat only months before on the federal appeals court in Chicago, appeared on the presidents short list for the vacancy. But Trump chose instead another appeals court judge, Brett Kavanaugh. Im saving her for Ginsburg, he explained, words intended to assure any disappointed members of his base that while the devoutly Catholic mother of seven had been passed over for this vacancy, she would not be overlooked the next time.

The question, of coursereally the only questionwas whether there would be a next time. Not since Richard Nixon had there been three Supreme Court vacancies in a presidents first term. But no one could rule it out. The recent history of Supreme Court nominations was filled with the unexpected. Justice Antonin Scalia, revered on the right almost to the point of worship, had died unexpectedly in February 2016, near the start of President Barack Obamas final year in office. Barely an hour after word came of the justices death, well before most Americans had even heard the news on that Saturday afternoon, Senator McConnell had declared that he would not permit the president to fill the vacancy. The American people should have a voice in the selection of their next Supreme Court justice, McConnell said. Therefore, this vacancy should not be filled until we have a new president.

It was an eyebrow-raising, norm-shattering proposition. While it was generally assumed that the Supreme Court confirmation door would close at some point during an election year, no one had questioned the propriety of filling a seat only a few months in. After all, Anthony Kennedy, President Ronald Reagans eventual choice for the court after the prolonged battle that ended in the defeat of Robert Bork, was not confirmed until February 1988, another presidential election year. McConnells challenge sounded like just so much bluster. But his word held. The Senate never gave a hearing to Obamas nominee, Merrick Garland, chief judge of the federal appeals court in Washington, D.C., a widely admired figure who had drawn praise in the past from leading Republicans, suddenly grown silent.

Eleven days after taking office, Trump nominated Neil Gorsuch, a judge on the federal appeals court in Denver, for the Scalia vacancy. When Democrats threatened a filibuster to protest filling what they deemed a stolen seat, the Republican majority changed the rules and abolished the filibuster for Supreme Court nominations. Gorsuch was confirmed by a vote of 54 to 45 (60 votes would have been required to break a filibuster) and took his seat in April 2017, in time for the final round of arguments in the 201617 term. His tenure as the courts junior justice was brief. Trumps second Supreme Court nominee, Brett Kavanaughlike Merrick Garland a judge on the United States Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit, usually referred to as the D.C. Circuitwas confirmed to the Kennedy vacancy the next year.