Map by Martin Brown

For the people who have suffered and lost during the Covid-19 pandemic, those who have cared for and provided aid to others during the pandemic, and those brave whistleblowers, doctors, scientists, journalists and sleuths who have persisted in seeking and sharing the truth.

Contents

The true laboratory is the mind, where behind illusions we uncover the laws of truth.

S IR J AGADISH C HANDRA B OSE

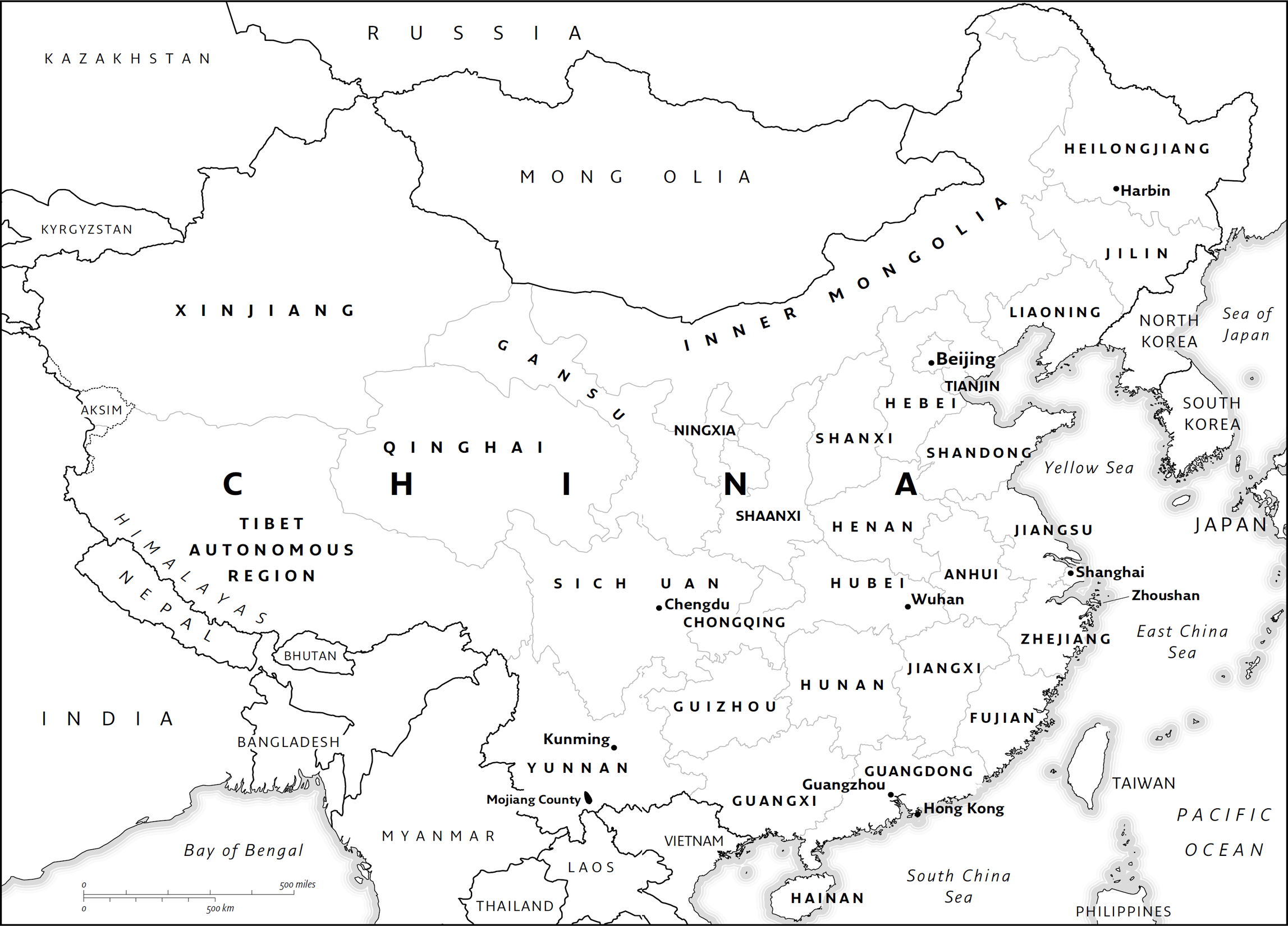

The authors of this book, Alina Chan, a scientist in the United States, and Matt Ridley, a science writer in the United Kingdom, have found ourselves inexorably drawn into the mystery of how the Covid-19 pandemic began. Over the past year, we have each pursued surprising revelations and rumours swirling around the origin of the virus. These took us deep into details of bats and SARS viruses in southern China, sick pangolins confiscated from smugglers, and cutting-edge gain-of-function virus research carried out in laboratories in Wuhan and elsewhere. In particular, Alinas life has been forever changed after plunging into the question of the origin of SARS-CoV-2, the causative agent of Covid-19, in May 2020. Her social media has since been transformed into an open forum where prominent scientists and internet sleuths spar, publicly, on the topic.

In April 2020 Matt wrote an essay for the Wall Street Journal about the viruss origin, headlined The Bats Behind the Pandemic, focused on the puzzling similarity of part of the SARS-CoV-2 genome to that of a virus from a pangolin a small ant eater while most of the genome resembled that of a bat virus. (A genome is the full genetic sequence of a creature.) He then read the preprint of a paper by Alina and two colleagues, Shing Hei Zhan and Ben Deverman, which came to the stark conclusion: Our observations suggest that by the time SARS-CoV-2 was first detected in late 2019, it was already pre-adapted to human transmission to an extent similar to late epidemic SARS-CoV. Noticing that Dr Zhan was an expert on genomic analysis and the other two were specialists in viral vector engineering at the elite Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, Matt judged that this preprint a scientific paper yet to be peer-reviewed for publication was probably a careful and reputable study. It had come to an electrifying conclusion: the virus causing the pandemic was evolving more slowly than one newly arrived in the human species from another animal normally would. This implied it was already well adapted to human beings from the moment it was first detected in Wuhan in December 2019.

On 21 May 2020, Matt wrote to Gary Rosen, an editor at the Wall Street Journal, proposing an article to revisit the origin question, centred on the new paper: There is one new paper in particular that has really thrown the issue back into the melting pot, he wrote. A team of scientists finds that unlike SARS, this virus showed very little rapid adaptation/evolution in the early weeks of the epidemic, implying it was already settled into its final form. This implies that the source was almost certainly not via pangolins and probably not the wet market. It was more likely brought to the market by a person not an animal. So we dont know where it came from and that implies the source is still out there. Bad news.

The newspaper commissioned him to write the article, so he contacted Dr Zhan and sent him a series of questions to try to understand the implications of the work for the origin of the virus. Clearly, one of the ways that a virus could have become well adapted for humans, in the words of the papers title, was by having spent time in human cells or in a so-called humanised animal in the laboratory. Humanised animals, usually mice, have had their genomes altered to include a key human gene, in this case the entry receptor for certain SARS-related coronaviruses. At the time, a laboratory accident or leak still did not seem likely to Matt. He wrote to Dr Zhan: Id like to focus on the issue of the lack of an apparent adaptive period of rapid genetic substitution, and its implication that the virus had been circulating in human beings for longer than expected. (I am not focusing on the lab-leak possibility, though I will probably mention it among other possibilities.)

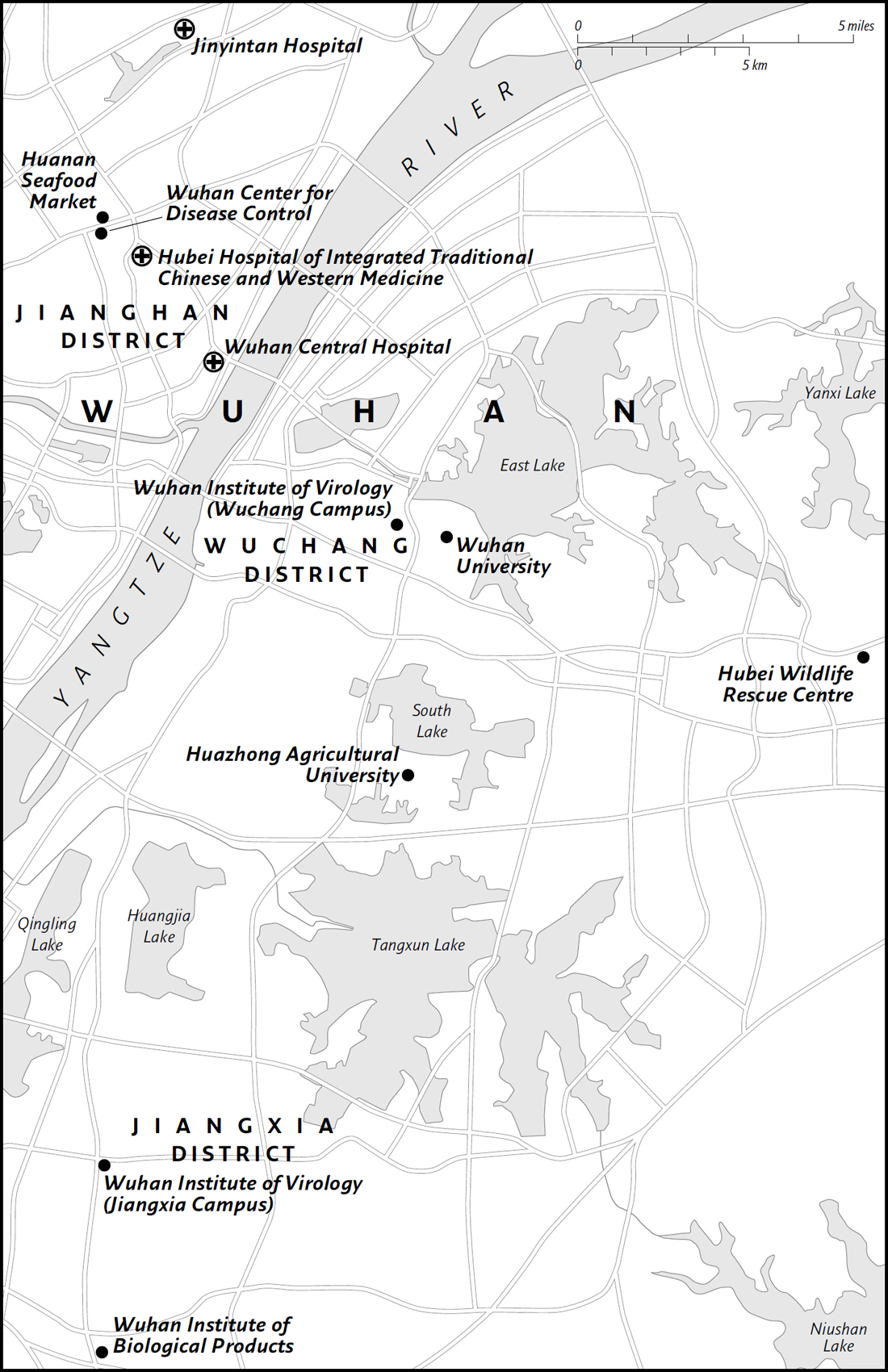

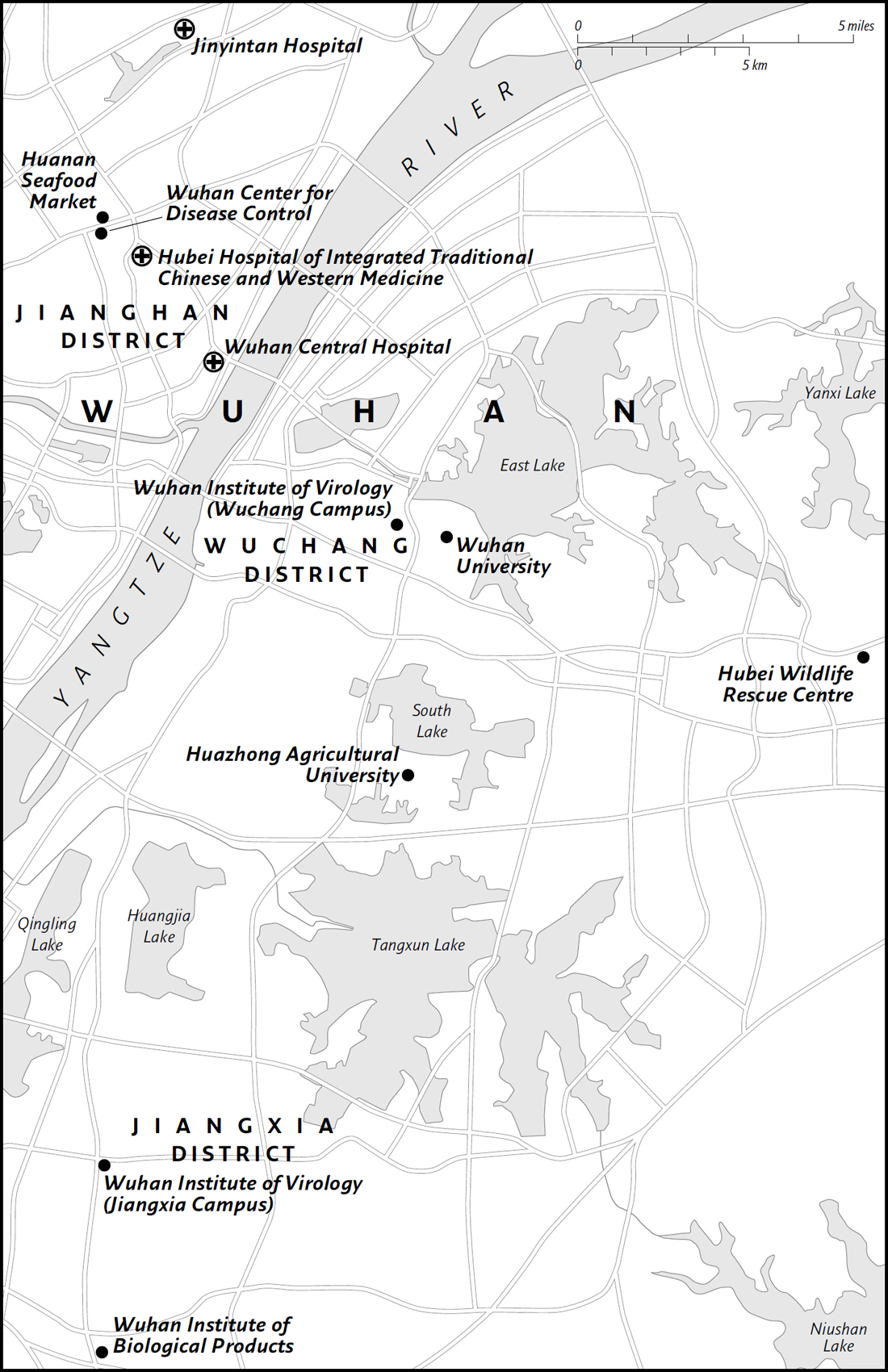

He received a lengthy, detailed and fascinating reply from Dr Zhans co-author, Alina. To Matts surprise, Alina did not pour cold water on his growing suspicions that a laboratory leak could not be ruled out. Indeed, she alerted him to a low-key announcement that week from the Chinese authorities that no animals in the Huanan seafood market in Wuhan had tested positive. This was consistent with the findings she and her colleagues reported in their paper that the market samples are genetically identical to human SARS-CoV-2 isolates and were therefore most likely from human sources. On 29 May 2020, the Wall Street Journal published Matts essay under the headline So Where Did This Virus Come From? The article began: New research has deepened, rather than dispelled, the mystery surrounding the origin of the coronavirus responsible for Covid-19. Bats, wildlife markets, possibly pangolins and perhaps laboratories may all have played some role, but the simple story of an animal in a market infected by a bat that then infected several human beings no longer looks credible.

Over the next several months, increasingly intrigued by the failure to turn up evidence of a chain of infections in a market, a village or anywhere else, Matt came to rely more and more on Alinas advice and insight as he pursued the story of the viruss origin. Eventually, he proposed that they join forces to write this book. By the time they finished writing it, because of the pandemic, they still had not met in person.

The importance of finding the origin of Covid-19

How the Covid-19 pandemic started may be the keenest mystery of our lifetime. The saga will forever punctuate the history of humanity. It has led to the deaths of millions of people, sickened hundreds of millions and dramatically changed the lives of almost every person on the planet. The impact of this invisible virus can also be measured in weddings and gatherings cancelled, jobs lost and businesses bankrupted, schools closed and parents balancing childcare and work, clinical visits missed and treatments put on hold, and innumerable people living more isolated lives than before. If we do not find out how this pandemic began, we are ill-equipped to know when, where and how the next pandemic may start.

In 2019, with more than seven billion human beings crowding the planet, crushed into dense cities, travelling frequently and far, the world was akin to a forest of dry tinder poised for a pandemic to ignite. Yet infectious diseases were in rapid retreat. The great killers of the past were under better control. Smallpox was extinct, polio endangered, typhoid rare, plague suppressed, malaria retreating, tuberculosis at a lower level than for most past centuries. Even AIDS, which emerged in the 1980s, was killing fewer people every year thanks to new treatments and public health interventions.

With each passing year the scientific tools and resources available for tracking and controlling outbreaks became ever more ingenious. A new pathogen could be detected, isolated and analysed with unprecedented speed and precision. Its genome could be sequenced, its structure elaborated and its weaknesses probed as never before. From time to time a new scare would threaten: SARS, MERS, Ebola, Zika. However, many imagined that infectious and deadly pandemics would, in the near future, be consigned to history. Few envisaged that a pandemic of Covid-19 proportions was about to begin.