A.K. Voronsky - Scoundrels and Toadies

Here you can read online A.K. Voronsky - Scoundrels and Toadies full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

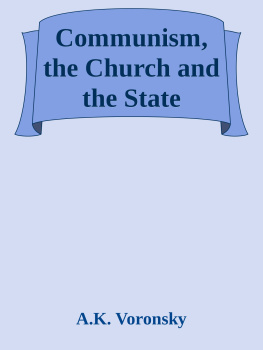

- Book:Scoundrels and Toadies

- Author:

- Genre:

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Scoundrels and Toadies: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Scoundrels and Toadies" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Scoundrels and Toadies — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Scoundrels and Toadies" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

During the years of my homeless, underground wanderings; of sleeping in conspiratorial apartments; of prison cells and transfers along the way to exile; during years of forced inactivity among the swamps and fog of the gloomy North, and of lonely and wearisome nightsI harbored a stubborn and inexhaustible hatred for the literary toadies inhabiting the newspaper and journal world of that time. Their venal adaptability, cowardly wiliness and open flattery went hand in hand with their self-confident insolence, monstrous superficiality, dubious know-it-all behavior, loose familiarity and hail-fellow-well-met attitude. Whenever I accidentally found myself in their midst, I always began to feel that the human heart and mind had created nothing of value. The most cherished thoughts and impulses suddenly faded, and I began to feel bored; indeed a gray emptiness engulfed me, so great was their cynicism.

When the first revolution was pushed back and bodies of executed prisoners swayed in the predawn wind; when prison fetters rattled beneath vaulted cells in the north, south, east and westthese newspaper satirists, scathing review- ers, and authors of bold articles and short pieces, before anyone else and in plain view of allrenounced what they had seemingly so fervently defended not so long ago. And they did even worse. Using the printing press for the fun and profit of all the spirits who had barely recovered from the revolutionary shocks, but who had already become fat and brutish, they mocked, reviled, denounced and slandered those who had not surrendered to the enemy. During the war years they performed one of the most despicable of comedies: they wrote about the second patriotic war, about the new tsar-emancipator, about the courageous and mighty victories of the glorious Russian troops. They wrote in this vein right up until the moment when these same troops used bayonets and rifle-butts to drive them out of their editorial offices, studies, cabarets and cafs. Scattering with a flutter of coattails, overcoats and pigtails, losing their galoshes, pince-nez and newsrags, they disappeared in an instant. Some fled abroad, others sat it out God knows where. These were the best of times. Then I fell victim to an illusion which was completely logical during those amazing days. It seemed to me that the newspaper and magazine vermin had scurried away for all time. I praised both the bayonets and divine obscenities of the soldiers who had crawled out of the trenches. I praised them because they had driven away the hacks and brigands of the pen.

...Now I know that I was naive. The very moment that we began to ac- quire a new economy, a new culture and a new art, the literary toadies and scoundrels began to raise their heads, at first timidly and then with ever greater confidence. But what is worse, the former literary do-nothings were joined by new, younger ones. There was life in the old dogs yet! It turns out that it was much easier to shatter tsarism, drive out the landowners and capitalists, repulse the attacks of the twenty tongues and lay the foundations to the edifice being newly erected than to crush this scoundrel.

The devil only knows what holes and cracks he crawls out of. But he has already laid out his notebooks, straightened out his pince-nez and found a new suit. He speaks with a deferential, ingratiating, but velvety and sonorous voice. He scurries here and there, first with a pleasant smile, then with a furrowed brow, sometimes with a weighty naturalness, sometimes with a grandiose or light offhandedness; he is satisfied, satiated and indefatigable. He has already become impudent. Throwing back his hair, he becomes inspired, dashes off some lines, then makes some arrangements and organizes some endeavor. One minute he flies by in an automobile with a well-known communist, the next minute he moves around the editorial office authoritativelyand then hes gone; hes already busy with some new people. Nothing fazes him; he is driven away from one place and he shows up in another, he is unassailable and indestructible. Not long ago he busied himself with organizing some kind of ultramodern theaterbut that collapsed. Then he gathered some artists around himself and tried to create a new tendency, but that fell through. Then he started to write a novel, but never reached the end. He did, however, receive an advance for a conspectus of the novel which was submitted in good time. He belonged to some secretariats, founded a journal, fussed over an exhibition, and gave some lectures about worker- and village-correspondents.

There are many varieties of literary scoundrels, but there are two main types: some energetically foonction, while the others foonction altogether quietly. But the quiet toady deserves something too. Not long ago I met such a type; he crawled into the editorial office like an ingratiating louse. Twisting his beard, he latched onto the sleeve of the editor, and holding him lightly by the elbow, pulled at the buttons of the mans jacket. The editor was a bit taken aback, but then the eyes of the quiet scoundrel were on the verge of shedding tears of entreaty. Then his eyes began to take everything in with an all-enveloping stare, they shone moistly and sweetly, and their attractive and engulfing power was stronger and more irresistible than the gaze of a boa constrictor. The poor editor was unable to resist. The quiet scoundrel received some kind of commission. When he had left, I asked the editor why he hadnt refused, for the fellow was an obvious rascal. The editor sighed in agreement: yes, of course, and the worst kind!

Everyone knows that passionate literary debates are still taking place. There are two literary camps, and here the scoundrel and rogue are having a field day.

How is this done? Very simply!

A smart fellow walks into the editorial office. He is free-and-easy, but modest. He has small, but sharp and shifty eyes. He wants to publish something. After a few days the editors return his manuscript, letting him know that they hold different, and you could even say, absolutely opposing views.

Indeed, the sharp-witted rascal agrees as fast as lightning, maybe you are right. Ill rework it....

?...

Let us further assume that the reworking has not even been successful. Two or three weeks pass. The scoundrel takes up arms in the other camp. Thats all there is to it. And about a week later, at one of the literary gatherings you hear, with gaping mouth and bulging eyes, his impassioned speech about the social command of the proletariat or something else in the same vein. Today he is a fervent Freudian, and tomorrow he will adhere to the strictest Plekha- novian orthodoxy, although he has heard about Plekhanov fourth-hand. Today he will extol Pilniak, and tomorrow he will accuse a genuine proletarian poet of petty-bourgeois deviations. He has already become hardened and merciless, he is ideologically consistent to the last neuron of his nervous system.

But his main energy is devoted to following the situation with his restless and attentive eyes; depending on which way the wind is blowing, his ideology and his entire appearance change accordingly. Cold irreconcilability and patronizing self-assurance give way to an obliging readiness to sacrifice his skin for you.

We have no small number of literary simpletons, of people who make mistakes, get carried away, who underestimate, bite off more than they can chew, or fall flat on their face; people who are infected with circle or group attitudes, or with communist-boasting. The scoundrel and intriguer is from another category: he is quite different. He never gets carried away, because he is too calculating. His inner core is as cold and amorphous as aspic. But he is always running ahead. He adapts himself to unknown and incidental people. Therefore he almost always is excessive in his statements. He extols the poet or prose writer who should still study his craft and jealously hide his filled-up pages and notebooks from others; but he mutters something incoherent and ill-willed about a major young talent; he is immoderate in his praise and damnation, he will go on at great length about Leninism, yes, of course, about Leninism, until you dont feel quite right; he, the scoundrel feels no qualms about referring in a speech, in a debate or in an article to a private conversation, or to one which he has overheard. He doesnt know the difference between a literary debate and a denunciation. By the way, the literary simpleton doesnt know the difference here, but the scoundrel and intriguer knows. Oh, how well he knows!

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Scoundrels and Toadies»

Look at similar books to Scoundrels and Toadies. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Scoundrels and Toadies and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.