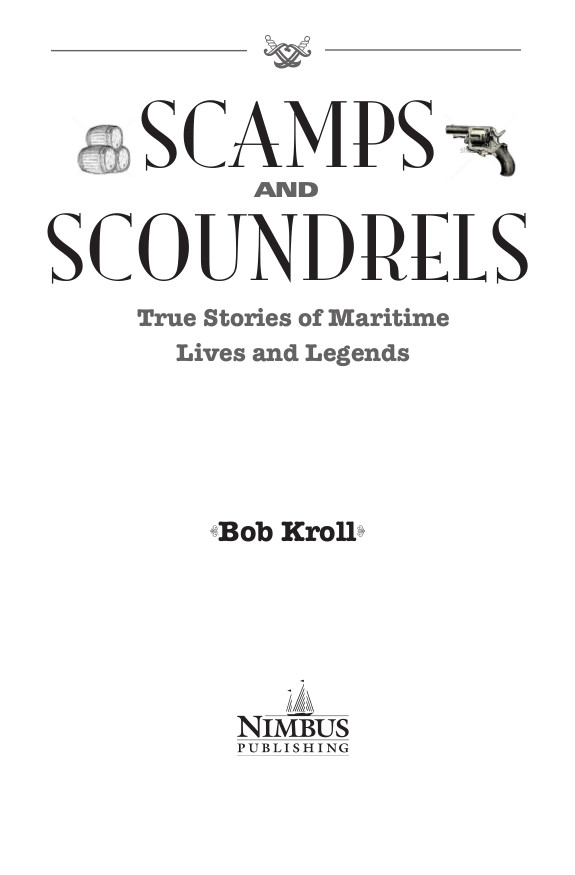

Title Page

Copyright

Copyright 2013, Bob Kroll

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission from the publisher, or, in the case of photocopying or other reprographic copying, permission from Access Copyright, 1 Yonge Street, Suite 1900, Toronto, Ontario M5E 1E5.

Nimbus Publishing Limited

3731 Mackintosh St, Halifax, NS B3K 5A5

(902) 455-4286 nimbus.ca

Printed and bound in Canada

Author photo: Mary Reardon

Interior and cover design: Jenn Embree

NB #: 1094

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Kroll, Robert E., 1947-, author

Scamps and scoundrels : true stories of Maritime lives

and legends / Bob Kroll.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-77108-034-7 (pbk.).ISBN 978-1-77108-035-4 (pdf).ISBN 978-1-77108-037-8 (mobi).ISBN 978-1-77108-036-1 (epub)

1. Maritime ProvincesBiography. 2. Maritime ProvincesHistoryMiscellanea. I. Title.

FC2029.K763 2013 971.50099 C2013-903462-5

C2013-903463-3

Nimbus Publishing acknowledges the financial support for its publishing activities from the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CBF) and the Canada Council for the Arts, and from the Province of Nova Scotia through the Department of Communities, Culture and Heritage.

Dedication

For Karen

Contents

Preface

M y ancestors lived in obscurity. Yours probably did too. We will not see our family names on urban street signs or carved into signposts along country roads. We will not find the lives of our ancestors recorded in history books or televised in film documentaries. There is little lustre to most of our family names and little glamour to the daily doings of our ancestors.

With some digging into historical records, we might find our ancestors names on military muster roles, on ships passenger lists, or among the names drawn for house lots in the first weeks of a settlement. The names of our ancestors might be found on deeds, wills, and church registers. Some may only appear on the back pages of a family Bible or chiselled into cold stone in a cemetery. And a few of us might even discover an ancestor among the dusty files of the criminal courts.

For most of us, our ancestors were everyday men and women who preserved their names in the lives of their children and their childrens children. They were common people who wrote their lives in the mud and rocks of the Maritime provinces; people who wore gristle from bone in relative obscurity and left to history not much more than a ragged scrap about their lives and the family legacy of their names.

I collected and wrote the following stories for these ordinary people. I tried to gather the ragged scraps of their lives and braid them into a narrative that reflects the everyday of the long ago. I also tried to capture the colour of the times in which they lived and the flavour of their language.

Some of the stories are tender. Some are humorous. Some are tragic. Others are brutal. Still others reflect men and women caught in the maelstrom of living. The stories are true. The people were real.

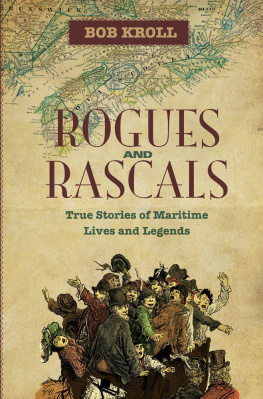

As in my previous collection of true stories of Maritime lives, Rogues and Rascals, the historical sources for the following are principally government documents, newspapers, court cases, coroner reports, grand jury books, police blotters, family papers, diaries, scrapbooks, local histories, and secondary sources.

It took more than thirty years to research these stories. I did not do it alone. Heidi MacDonald helped research Prince Edward Island, and B.J. Grant covered off New Brunswick.

B. K.

Jack Sauce and Billy Be-Goddamned

You Cant Fight City Hall

Ben Shorer risked his life cutting firewood for the Halifax settlers and mast spars for His Majestys government. He had a small schooner that he sailed along the Nova Scotia coast and into various coves and inlets. He and others would anchor, row ashore, and knock down a few trees, then limb them and chunk up the branches into firewood. They would cut tree trunks to length for building boards, and longer ones for mast spars. It would take the logging crew nearly a week to get a load. And thats where the part about Ben Shorer risking his life comes in.

This was in the years between 1749 and 1757, and Ben was working outside the protection of the palisade that surrounded the settlement of Halifax. He carried a musket and an old navy pistol, but they hardly afforded the protection he would need if a few Mikmaq warriors and a patrol of French soldiers happened by. England was still at odds with France, and the French were allies with the Mikmaq, and neither cared much for the English.

One would think Bens firewood and mast spars came at a premium, due to his working away from home under circumstances that increased the chance of losing his life. But the government took a different view. It discounted Bens services and undervalued his products. Sometimes the government paid less than Bens asking price. At other times, it didnt pay him at all.

On March 29, 1757, Ben Shorer petitioned the Nova Scotia government for money it owed him for firewood and mast spars. Charles Lawrence was governor of the province, and when he read Bens petition, he refused. Governor Lawrence offered no explanation. He just ordered the government paymaster not to pay. And when Ben complained, perhaps a little too loudly, the provost marshal visited Bens lumberyard and charged him with unlawfully selling beer and spirits.

In his petition, Ben claimed the charge was bogus, a way for the government to get out of paying what it owed. He also noted that his trial before a judge, without a jury being present, was unjust. The only witness against Ben was one of his own servants, and that man had held a grudge against Ben from the first days of his indenture in Bens household. On top of that, the judge did not give Bens testimony any credence, and when Ben linked the charge with the government owing him money, the judge gavelled him into silence.

Ben was convicted, fined five pounds, and sentenced to a public whipping of thirty-nine lashes. The whipping was later dropped, but the fine stuck, and Ben had to sell his schooner to pay it.

Theres a lesson in this story, one most of us already knowno matter how just your cause or how right you are, you cant fight city hall.

Like Ben Shorer, John Grant learned that lesson the hard way. On March 5, 1757, he complained to the Lords of Trade that Governor Lawrence was financially cheating the province. Grant cited several instances in which the governor and his cronies used government bounties for their own benefit. He explained that bureaucrats would draw up exorbitant estimates for government work and contracts. Then, without going to public tender, the governor issued those contracts to his friends.

Ten days later, Governor Lawrence got even. He ordered John Grants house pulled down and offered the Halifax merchant no compensation. Grant fired off another petition, and this time the governor retaliated by ordering other merchants not to trade with John Grant, going so far as to encourage them to end their friendships with him. Since Halifax businessmen depended on government contracts, most complied with the governors order. John Grant went out of business and was socially ostracized.