A catalogue record for this book is available from the National Library of New Zealand.

The moral rights of the author have been asserted.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

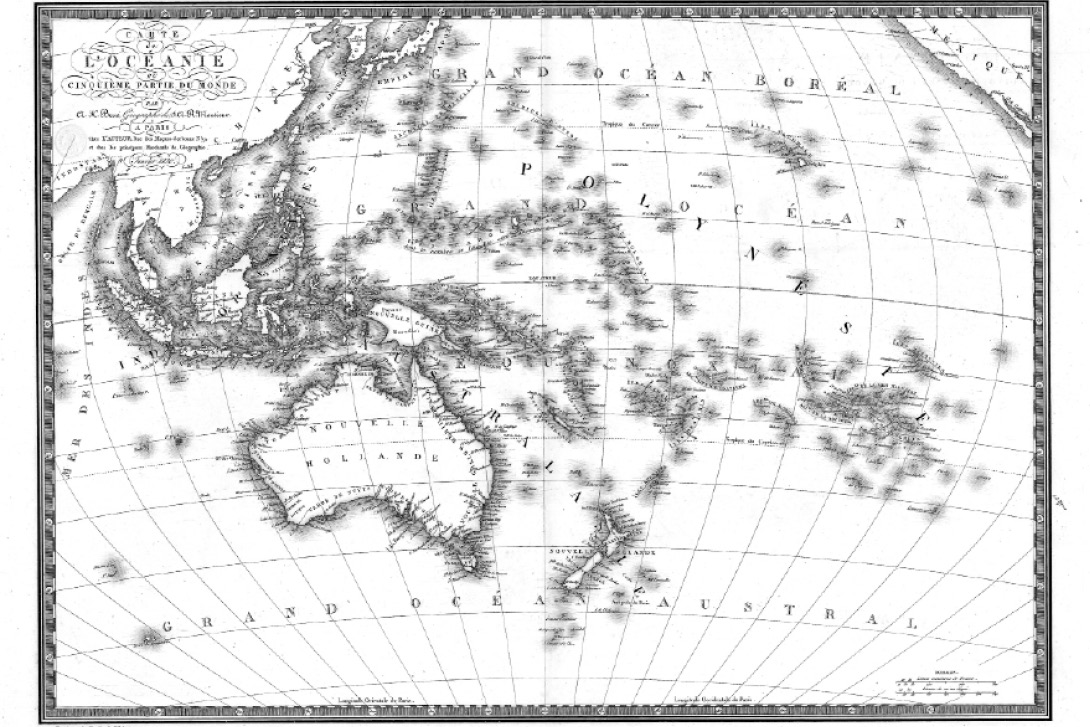

Map of Oceania drawn in 1820.

Foreword

The Pacific Ocean was the last region to be discovered and explored by Europeans. Even for those who lived along its shores, it was a world of mystery, danger and legend. Venturing into its vastness was often considered unwise, and in most cases the earliest settlers, mostly from Asia and its outlying islands, had sailed into it to avoid some invasion or some threat from their own region, hoping that they might find a new and safer home on an uninhabited island. This had taken centuries and the islands of the Pacific eventually each presented their own private world, with their own legends, their way of life and their traditions.

The Europeans came much later, with discoveries, often unexpected, gradual exploration, followed by venturesome trade, settlement, exploitation and colonisation. The great powers tried to exclude each other and create their own empire first the Spanish and the Dutch, then the British, the French, the Germans and in time the Japanese. But in between, there were raiders, pirates, thieves, private individuals who worked and often cheated in the hope of building their own little world, exploiting an ocean which was only slowly being controlled and brought into the theoretical orderliness that dominated the rest of the world.

This is a small collection of the tales that have been told of the men, and in some cases the women, who sought to benefit from the discoveries of the early explorers, scoundrels and rogues with little conscience but great craftiness, and of those who as a result found themselves victims of situations they could hardly imagine. It shows that humankind, in whatever period and whatever part of the world, may have its heroes, but it always has its villains.

Chinese Explorer or Conman?

T o the people who lived along the coasts, the Pacific Ocean was the edge of the world. They stared out at this immensity of water, sometimes placid, more often angry, as they might at eternity itself. It might hold promise for a few; for some it was a world of legend, with mythical heroes and monsters, but it held terror for most. Wise indeed were those who merely took it for granted, something about which one did not speculate, a foreign world that was incomprehensible or meaningless. One could fish and sail along the shore, usually in some frail craft, but one would be unwise to venture out too far, out of sight of land, for one might never return.

To the Chinese, living in what most believed was the centre of the world, the Middle Kingdom, the sea was one of the limits of the universe. No one could live out there, certainly not human beings. It was a world of strange aliens, possibly the abode of the Immortals, but certainly one of mystery. For centuries, the Chinese built their empire across Asia, leaving the ocean to itself.

Those who lived close to the great rivers, such as the Yangtze and the Yellow River, the Huang He, and saw them roaring towards the ocean, swollen by heavy inland rains, overflowing and flooding into the rice fields, believed that there was a giant maelstrom out in the ocean, the Wei Lu, a great hole into which poured the water, taking with it any unfortunate craft that had ventured too close to it. If there was no such plughole, then the waters would rise up everywhere and flood the world. It was much more logical to believe in this Wei Lu, where the waters poured down into the earth and, after being cleansed in the underworld, re-emerged as bubbling springs in the mountain ranges or rose in spiralling clouds over the horizon. This belief remained widely held for centuries, because as late as the 13th century of the modern era the historian Chau Ju Kua, the author of Zhu Fan Zhi , or A Description of Barbarous People , reminded his readers of the Great Hole of Wei Lu, where waters drain into the world from which men do not return.

The old legends also spoke of Fu Sang, a paradise somewhere beyond the horizon, a magical place where enchanters dwelt, where silkworms grew two metres long, and where the herb of eternal youth might be found. Immortality is a theme that was often found in the old legends that were narrated around the fire or discussed in temples.

Stories these might be, but some began to dream of going to see for themselves. Around the year 219 B.C., the Emperor Shi Huang Ti raised the question with one of his courtiers, Hsu Fu, or Xu Fu, who had a reputation as a skilled man and also as a sorcerer. Shi Huang Ti could look back on his own life with a great deal of satisfaction: he had started in 245 B.C. as a mere local ruler, but in less than 20 years he had unified China under his rule. He had reorganised the country, extended its frontier to the edges of Vietnam and Korea, had had a great wall built to keep out intruders, and was now ruling a vast empire with great efficiency and ruthlessness. His dynasty, the Qin or Chin, would give the country its name, and as a ruler he was both admired and feared.

Emperor Shi Huang Ti

However, one thing worried him, as he grew older, and that was the prospect of death. His name, he knew, would become immortal, his body would be preserved in a great mausoleum and guarded by an army of small soldier-like figurines, but his life would have ended, and he would know nothing of what the future might hold. He had heard, however, like most of the Chinese, of wondrous islands far off in the Pacific Ocean, where there grew a magic herb that ensured eternal life. The plant of immortality might be a myth, but it was worth a try, a feeling that grew after at least one assassination attempt and the onset of middle age. His courtier suggested that he could sail off in the name of the emperor, using his own great talents to deal with whatever magic islands he might encounter. Shi Huang Ti agreed and supplied him with the ships, made mostly of bamboo, and the crews and supplies he would need.

Hsu Fu is reported to have set out on his first expedition early in the year 219 B.C. He is said to have sailed from the ancient city of Lang Yu in Shantung province with a small fleet of large bamboo ships and to have begun his search for the islands where the Immortals lived, with the mission of persuading them to share their wonderful herb to preserve the life of the great Chinese emperor. He probably thought it a wise move, as he was only in his early thirties and he feared the struggles for succession that would inevitably occur after the emperors death and which, as one of the elderly rulers prized courtiers, would probably cost him his life.