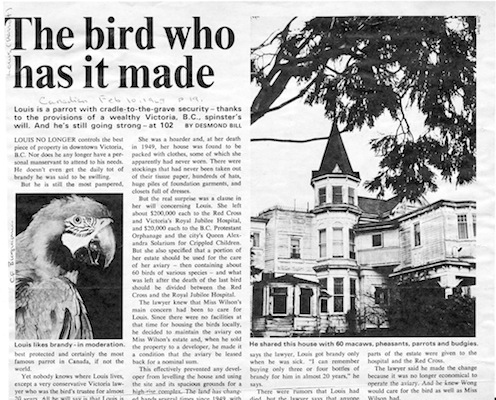

LOUIS THE PARROT NO LONGER rules the roost in Victoria. Once, he was the most famous media personality in town and had a manservant to tend to his every need. He ate walnuts, hard-boiled eggs, and brandy, and lived on a prime chunk of downtown real estate.

But Victorians liked Louis. They liked his regal lifestyle and his thumbing his nose at the way of progress. They were happy to see him live out his long life in splendour. This was some recompense, they felt, for the sad life his mistress had had to live.

Louis the Parrot.

Louiss story is really that of Victoria Jane Wilson, who acquired Louis when she was still a little girl. She was born in 1877 in Victoria. Her father, Keith Wilson, was a real estate tycoon, and her mother, Mary, was descended from early fur traders in Victoria. Growing up, Victoria Jane had a comfortable, but very closeted, existence.

Her father, for reasons best known to himself, did not want her to meet strangers, especially men. Perhaps he thought fortune hunters would try to grab her.

Whatever the reason, her seclusion became something of a scandal in Victoria.

James Nesbitt had a story to tell about this. As a boy, he would deliver newspapers to the Wilson household. Victoria Jane was there every day to get the paper from him. But she rarely said a word. No wonder, for fifty feet away stood her father, glowering at the paperboy. As Nesbitt said, he was standing there making sure that the paperboy did not run after his daughter.

On the few occasions when Victoria Jane did leave the house, her father would follow her. He would be hovering in the background, occasionally dodging behind poles if she happened to talk to someone. No wonder she grew up to be a painfully shy recluse.

Birds became her true love. Enter Louis. She was given Louis when she was five, and he quickly became the love of her life. Many other birds followed. Over the years, she bought budgies, love birds, Panamanian parrots and various other species.

Eventually, her aviary was one of the largest of its kind in Victoria. It occupied the entire top floor of her house. But no matter how many birds she acquired, Louis always remained her favourite. He was, in fact, the major impetus in her one attempt to break free.

In the early 1900s, she bought a Hupp Yeats electric car. She wanted to learn how to drive and take Louis for a spin. She did take a few driving lessons. But Louis didnt take to motor cars. He didnt like the noise, and the fumes irritated his skin. So, sadly, the car went into the garage for good. By the time she died, the car had become sealed in the garage, and a wall had to be knocked down to get it out.

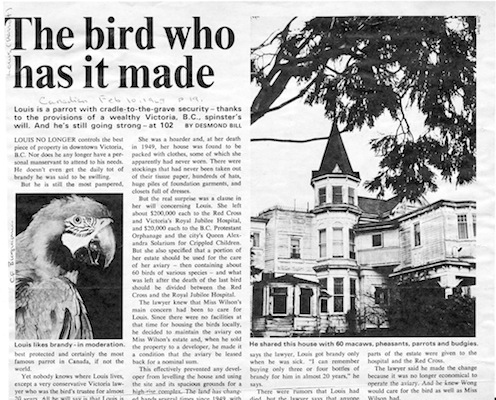

The story of Louis the Parrot became internationally famous. This photo of Louis with his caretaker appeared in Life magazine.

As the years wore on, her parents died. First her mother went in 1917. Now Victoria Jane had to look after her father. But seclusion had taken its toll. Long before her father died in 1934, she had become a full-fledged recluse, seldom going out or seeing people.

She did ease up a bit after his death. Nesbitt reports that she gave small, intimate dinner parties at the Empress and the Priory. She also liked to go on the occasional shopping spree for clothes and perfume. But it was too little, too late.

When Victoria Jane died in 1949, it was discovered she had an unusual bequest in her will. She left a substantial sum for the care of her birds. No institution would take them, so her lawyer decided they would be best off if they were left just where they were.

Her former servant, Wah Wong, was paid to take care of the birds. The Wilson property was sold. But the lawyer made it a condition that the house be leased back to the estate, so the birds could keep their home. This, of course, made it impossible to develop the property. The property changed hands several times, but the birds remained.

Over the years, the birds died, and eventually Louis was the only one left. But parrots live far longer than humans. No one knew exactly how old Louis was, but it was a sure bet that he would outlast all the humans around him. And he was definitely the favourite.

Louis in Canadian, February 10, 1969.

Eventually, a solution was found. In 1966, seventeen years after Victoria Janes death, Louis went to live with Wong. Money was provided for his care. And with Louis gone, the developers were free to develop the estate.

A big new hotel was built on the site of Louiss former home. For a few years, there was a restaurant on top of the Chateau Victoria called the Parrot House. But times change and memories fade.

Not long after the transfer, Wong died. While the family continued to care for Louis, he must have missed his friend. The Wong family would not talk, but there was a report that a few years later, Louis, too, had died. And, bowing to fading memories, the Parrot House changed its name. Louis, it would seem, was gone for good.

A good story, though, never dies. Who knows? Louis himself might still be around.

Postscript

The Hallmark Society is an organization dedicated to heritage preservation in the Capital Regional District. It has named its most prestigious honour the Louis Award, in memory of Louis and his demolished home. The award recognizes an exceptional heritage building restoration, one that demonstrates unusual attention to authenticity and structural integrity, and that has had an exemplary impact on a neighbourhood or region. As it recognizes only the truly exceptional, it is not awarded every year. The recipients are given something Louis would have approved of: walnuts and brandy.

The Yuquot

Whalers Shrine

IN THE EARLY 1990s SEVERAL groups of Mowachaht elders left their homes on Vancouver Island and travelled to New York. They had been invited by the American Museum of Natural History to see a mysterious object that had left their community ninety years ago. This object, the Yuquot Whalers Shrine, is composed of an original small building and its contents: 88 carved human figures, 4 carved whales, and 16 human skulls. It was collected in 1904 by George Hunt, acting on the instructions of a museum curator, Franz Boas. The shrine had been built over several generations by Mowachaht ancestors, but few living band members had seen it. The question hanging over the elders was this: should the shrine come back home? But an outsider might well ask another question: why is it in New York at all?

Strange as its presence might seem in New York, it is in fact far from unusual. The American Museum of Natural History has an enormous northwest Native art collection, the largest in the world. And New York is not alone. Museums throughout the world have substantial collections of this art. So the shrine is part of a huge transfer of art and artifacts, from the Pacific Northwest to the rest of the world. The question really is, why did this transfer occur? In their original home, the art and artifacts had meaning and relevance. To the rest of the world, they did not. To understand why this happened requires examining the eighteenth century, when the first contacts between Native people and Europeans occurred in the Pacific Northwest. Only by studying their relationship, and its subsequent developments, can the answer be found.