Acknowledgements

My thanks go to all those intrepid divers who have explored so many of the sunken shipwrecks in the Graveyard of the Pacific. Having experienced the underwater world a few times, I am in awe of your courage and tenacity.

Thanks also to the handful of nautical writers who have documented the stories of the people and ships that have braved the serrated coasts of western Vancouver Island. I am proud to stand among you.

Chuck Syme, a historical tour guide who specializes in the Gold River area of Vancouver Island, sent me his CD-ROM The Wreck of King David, which contains his excellent long poem about the ships last day and the suffering of her sailors. Thanks so much, Chuck, I enjoyed listening to your tale immensely. Thanks also to the authors of so many websites dealing with the individual tales of shipwrecks in this region. You made my research so much easier.

My gratitude goes to Heritage House publisher Rodger Touchie, who asked me to write this book, and to managing editor Vivian Sinclair for putting up with me again. It is always a pleasure working with you two and your team. Finally, thanks to Lesley Reynolds, my editor for this book, for her careful work.

About the Author

Anthony Dalton is the author of eight non-fiction books, many of which are about the sea or about ships and boats. These include Baychimo: Arctic Ghost Ship and Alone Against the Arctic , both published by Heritage House. Anthony teaches workshops across Canada and divides his time between homes on the mainland and in the Gulf Islands of British Columbia.

Bibliography

Bark Janet Cowan Wrecked. The New York Times , January 13, 1896.

Belyk, Robert C. Great Shipwrecks of the Pacific Coast . New York: Wiley, 2001.

Incidents of Soquel wreck. Victoria Daily Colonist , January 27, 1909, p. 10.

Mason, Adrienne. West Coast Adventures . Canmore, AB: Altitude Publishing Canada Ltd., 2003.

McClary, Daryl C., The SS Pacific founders off Cape Flattery with a loss of 275 lives on November 4, 1875. The State of Washington, Washington Department of Archaeology and Historic Preservation, 2009. http://www.historylink.org, file 8914.

McDowall, Duncan. HMCS Thiepval , The Accidental TouristDestination. Canadian Military History 9, no. 2 (summer 2000): 6978.

Neitzel, Michael C. The Valencia Tragedy . Victoria: Heritage House, 1995.

Rogers, Fred. Shipwrecks of British Columbia . Vancouver: J.J. Douglas, 1973.

_____. More Shipwrecks of British Columbia . Vancouver: Douglas & McIntyre, 1992.

Syme, Chuck. The Wreck of the King David . CD-ROM. Courtney, BC: Pickford Productions, 2008.

27 Lost with Bark. The New York Times , December 29, 1905.

United States Commission on Valencia Disaster. Wreck of the Steamer Valencia: Report to the President of the Federal Commission of Investigation . Seattle: Washington Government Printing Office, 1906.

Wells, R.E. The Loss of the Janet Cowan . Sooke, BC: R.E. Wells, 1989.

Contents

Copyright 2010 Anthony Dalton

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, audio recording or otherwisewithout the written permission of the publisher or a photocopying licence from Access Copyright, Toronto, Canada.

Originally published by Heritage House Publishing Co. Ltd. in 2010 in paperback with ISBN 978-1-926613-31-4.

This electronic edition was released in 2011.

e-pub ISBN: 978-1-926936-31-4

e-PDF ISBN: 978-1-926936-53-6

Cataloguing data available from Library and Archives Canada

Edited by Lesley Reynolds

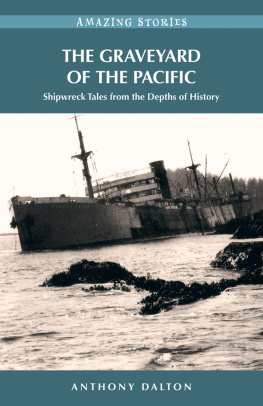

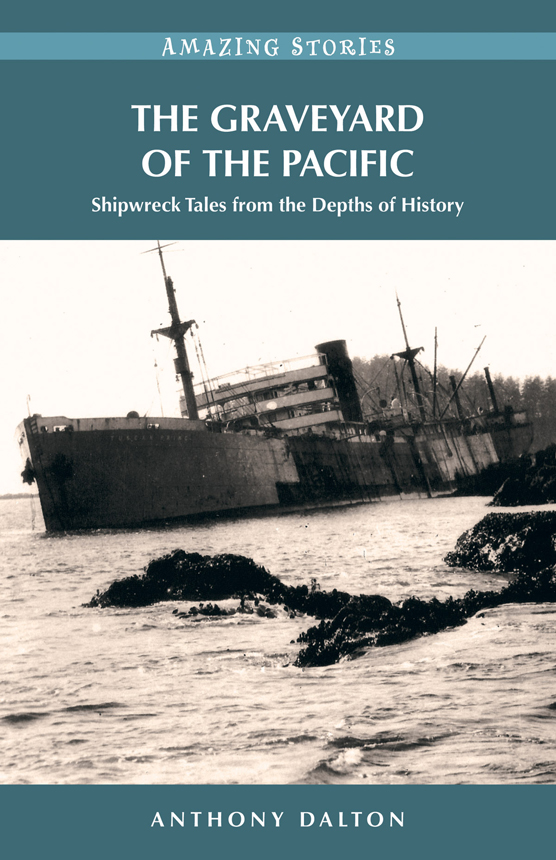

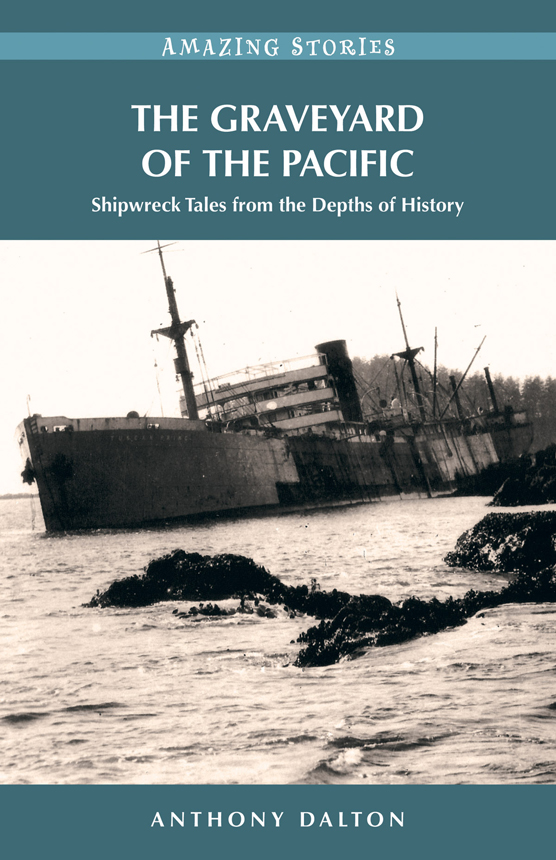

Cover photo of Tuscan Prince , aground on Village Island in Barkley Sound, courtesy of the Maritime Museum of BC

Heritage House acknowledges the financial support for its publishing program from the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund (CBF), Canada Council for the Arts and the province of British Columbia through the British Columbia Arts Council and the Book Publishing Tax Credit.

www.heritagehouse.ca

For all those who challenge the sea

Epilogue

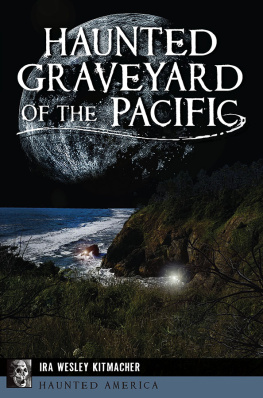

Today most of the shipwreck sites along the southwestern coast of Vancouver Island are well documented. Amateur and professional divers have explored many of them countless times, and local museums contain a rich variety of artifacts taken from the sites.

Inevitably, time, powerful storms and the ever-moving seas have conspired to tear the wrecks apart and bury their remains under accumulations of silt. Marine growth also obscures most of the debris, creating artificial reefs that become new habitat for sea creatures. The Barkley Sound wreck sites of HMCS Thiepval , Vanlene and Nikka are reasonably accessible and popular with knowledgeable divers.

Perhaps because of the increasing interest in shipwrecks, the waters of British Columbia, particularly around Vancouver Island, have become a mecca for divers from all over the world. The province is often listed as one of the top dive sites in North America. Those same waters are, however, extremely dangerous to all but the most skilled of underwater explorers. Fortunately, there are accredited dive schools and escorted dive programs for the less accomplished.

Although new shipwrecks are rare in todays technological world, occasionally a ship will still go astray and find herself in peril. They are rarely lost, however, and deaths by shipwreck today are uncommon.

Introduction

On cold, windy, wintry nights, when rain and snow bring visibility down to almost zero over the seas off the southwestern coast of Vancouver Island, one can almost hear the moans and groans and screechings of dying ships. Mixed with the unearthly sounds of tortured wood and metal are the low, mournful wailings of the ghosts of the long-dead passengers and crews who died on or close to the rocky shores. They were mostly men, but among them were a handful of women and a few children.

Most were within hours of the end of their voyages. Some were coming from California, others from far-distant foreign ports. A few were just setting out on their voyages. Without exception, none of them expected to be shipwrecked in the Graveyard of the Pacific. None of them were prepared to die so close to their destinations or their points of departure. Of the few who made it to shore, many died of exposure before they could be rescued.

It was because of these ill-fated ships and people, and for all those who would follow, that the now-famous West Coast Trail was originally developed. Between 1888 and 1890, the government strung a telegraph line through dense bush on the west coast of Vancouver Island, using traditional Native trails and linking villages and a couple of towns with the recently built lighthouses at Cape Beale and Carmanah Point.

Following the Valencia tragedy of January 1906, when far more than 100 people lost their lives, public opinion persuaded the government to do more in case of another equally deadly shipwreck. As a result, the Pachena Point lighthouse was built and a few life-saving stations were established. The barely visible telegraph trail was also greatly improved and marked so that shipwrecked mariners could find their way to safety.

Much later, the installation of radar on ships and the invention of other greatly improved navigational devices significantly reduced the number of shipping disasters on the coast until the life-saving trail was no longer considered necessary. It was abandoned and allowed to deteriorate. In 1973, the old trail became part of the brand new Pacific Rim National Park and was upgraded. Hikers now enjoy the trek along coastal trails where the ghosts of long-dead mariners may still roam.