CHAPTER

Who Was Henry Hudson?

HISTORIANS HAVE CONSISTENTLY DRAWN A blank when searching for clues to the early life of English sea captain Henry Hudson. He is, without doubt, one of the most enigmatic figures in the history of seventeenth-century polar exploration.

Hudson is thought to have been born either in Hertfordshire or somewhere in Greater London around 1570; some say he may have been born much farther north, in Northumberland. The mystery remains unsolved.

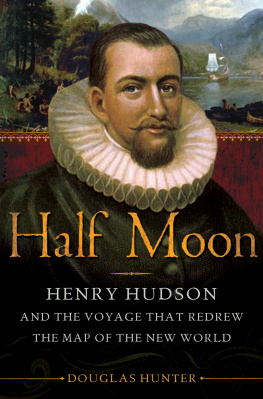

What he looked like is also unknown. Although there have been a few paintings and sketches of the man, these images are falsenothing more than guesswork on the part of the artists. No accurate pictorial record exists.

The first historical knowledge of Henry Hudson dates to 1607, when he was already in his thirties. So what was his life like during his formative years, and what was he doing during his twenties? There are no answers, only conjecture and supposition.

Henry Hudson is thought to have been the son of a sea merchant. The family is believed to have had connections, through Henrys grandfather, to the London-based Muscovy Company, an established English trading consortium in whose service Henry Hudson is believed to have gone to sea while he was still a boy. It is possible that young Henry served for a while as a cabin boy or common seaman under the great navigator and North Atlantic veteran Captain John Davis. If he did so, that would account for his considerable knowledge of northern regions and his undeniable sailing and navigation skills. Davis made three voyages to what is now the Canadian Arctic between 1585 and 1588 and would have known something about the treacherous strait between Baffin Island and the mainland. If Henry Hudson sailed with him, he would have learned much from Davis about navigating in ice.

However he came by his skills, at the dawn of 1607 Henry Hudson was, by the standards of the day, an educated man. He could read and write. He had a working knowledge of mathematics. He could understand and follow directions on maps and nautical charts, he was an experienced sailor who had advanced to the rank of ships captain, and he had a few influential friends. Those friends were important to Hudson because he was determined to make his name as an explorer. He needed to have a high profile to win future commissions.

Unfortunately, despite his status as a respected captain, Henry Hudson would prove to be devious in his dealings with his employers and would show that he was a poor judge of men. A captain was expected to stamp his authority on every aspect of his ship and his crews. In that, Henry Hudson was something of a failure. He often vacillated at sea, causing confusion among his officers and crews. He could be unnecessarily judgemental and often dangerously unfair in his decisions.

Away from the sea, Hudson appears to have been a happy family man, although obviously restless. He had a wife, three sons, and a granddaughter. Having a family, however, would not have prevented Hudson from accepting ocean-going commissions. It was not unusual in those days for seafarers to be away from home for many months at a timesometimes a year or longerwith no communication from home for most, if not all, that time. Hudsons wife, Katherine, might not have liked it, but she would have understood.

Henry Hudson is believed to have married Katherine (there is no record of her last name) in the early 1590s. They lived in some comfort, for the times, in a three-storey brick house in Londons St. Katherines district, within walking distance of the Tower of London. The house would have been a narrow structure with small rooms, but it would have been far more comfortable than the accommodation owned or rented by most mariners. That the Hudson family was well off financially is suggested by the fact that they had a live-in maid to take care of the house and their three sons, Oliver, John, and Richard. Little is known of Oliver, other than that he was married and had at least one child, a daughter.

By the early eighteenth century, British and other European sailing ships had roamed much of the globe. They knew the extent of the worlds oceans and the outlines of the continents. Spanish ships had been crossing the Atlantic to Central and South America for over two hundred yearsand they had explored significant parts of the South Pacific. Portuguese ships had rounded southern Africas Cape of Good Hope and crossed the Indian Ocean to trade with Asia. The Dutch had sailed and traded as far afield as modern-day Indonesia, and the British had left their national flag on the foreign soils of Africa, India, and North America.

What was missing from the nautical charts of the times was a clearly defined sea route across the top of the worldfrom Europe to Asia via a northeast or northwest passage, both of which would be icebound for most of each year.

Captain Henry Hudson, not yet a household name in England but building a reputation all the same in nautical circles, believed strongly in the existence of a northwest passage. He was also prepared to admit the possibility of a similar route to the northeast, across the northern shores of mighty Russia. If at all possible, he wanted to be the man to discover one or the other of these elusive northern passages.

CHAPTER

Discoverys Crew and Captain: What Happened to Them?

CAPTAIN HENRY HUDSON AND HIS small crew of castaways disappeared into history: none were ever seen or heard from again. Cast adrift by his mutinous crew in the southeastern half of Hudson Bay in June 1611, Hudson was accompanied by the following crew members: John Hudson, the captains teenaged son, who acted as ships boy and had served aboard all four of his fathers expeditions; Philip Staffe, the ships carpenter, who had remained loyal to his captain, whether he agreed with Hudsons decisions or not (although there were reports of Staffe openly refusing to obey orders, such as the one to build the house on the shore of James Bay, for the most part he had accepted the captains commands); the loyal John King, who had been promoted to mate after Robert Bylots demotion; Thomas Woodhouse, the young mathematician; Arnold Ludlowe, who had been injured by the spinning capstan when Discovery lost her anchor; Michael Butt, also injured by the spinning capstan; and, finally, loyal crew members Adrian Moore and Syracke Fanning.

Robert Juet, sometime first mate, sailed with Henry Hudson on three expeditionary voyages. Despite that, the two men had never got along. Juet was older than Hudson and an experienced sailor. Certainly guilty of aiding and abetting the Discovery mutiny in 1611, Juet was most likely one of the ringleaders. He died at sea of starvation during Discoverys homeward voyage after the mutiny. His body was committed to the Atlantic Ocean somewhere to the west of Ireland.

Robert Bylot is something of an enigma. Although he did not take part in the mutiny, he did nothing to prevent it or fight against the mutineers. He sailed home with the survivors and should have been hanged by association with the mutiny but was discharged without even a slap on the wrist. He became a respected and knowledgeable Arctic sailor, returning to Hudson Bay in 1612 as navigator under the command of Captain Thomas Button with Resolution and Discovery. In 1615 he was promoted to captain and, in an ironic twist of fate, was given command of Discovery. He made two more voyages to the Arctic, during which he proved himself to be a highly skilled ice pilot. He died, it is thought, in late 1616 after his return from the second voyage as Discoverys master. Bylot Island, off the north coast of Baffin Island, is named for him.

Abacuck Prickett was not a sailor. He had been placed on board by one of Hudsons benefactors, Sir Dudley Digges, to report on the voyage. Still, he would have been subject to the captains orders, no matter how unpleasant. Was he a mutineer, or was he an innocent bystander too ineffectual to stand by his captain? History says he was a mutineerbut he got away with it. He returned to Hudson Bay in 1612 as an able seaman, aboard

Next page