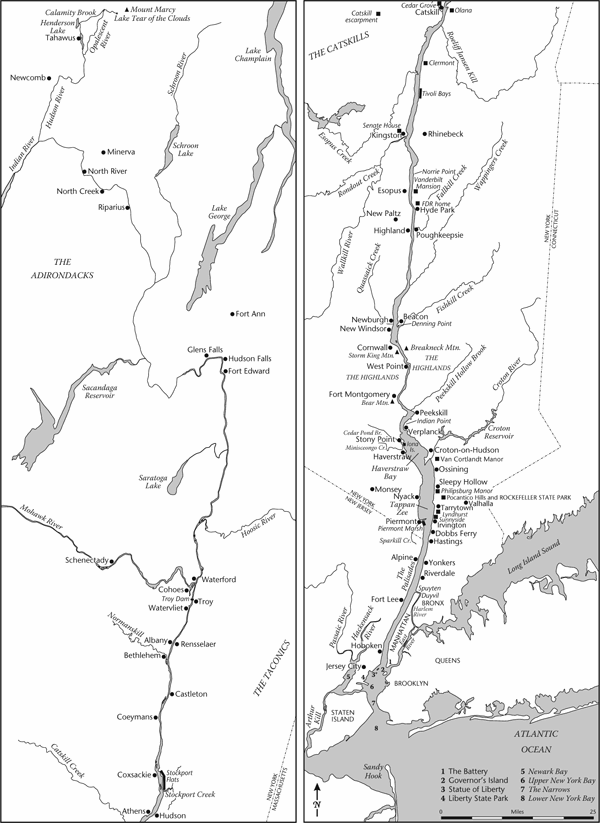

The Hudson

Winslow Homer, Hudson River, Logging. Watercolor and graphite on paper, 14 x 20 5/8 inches, 1892. In the collection of the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C., Museum purchase (03.4).

To my family and friends, and in particular to Franny Reese, without whom, in so many ways, this book could not have been written; to Wes, Davis, and Lia for their love; and to the Hudson, river of mystery, for its continual inspiration

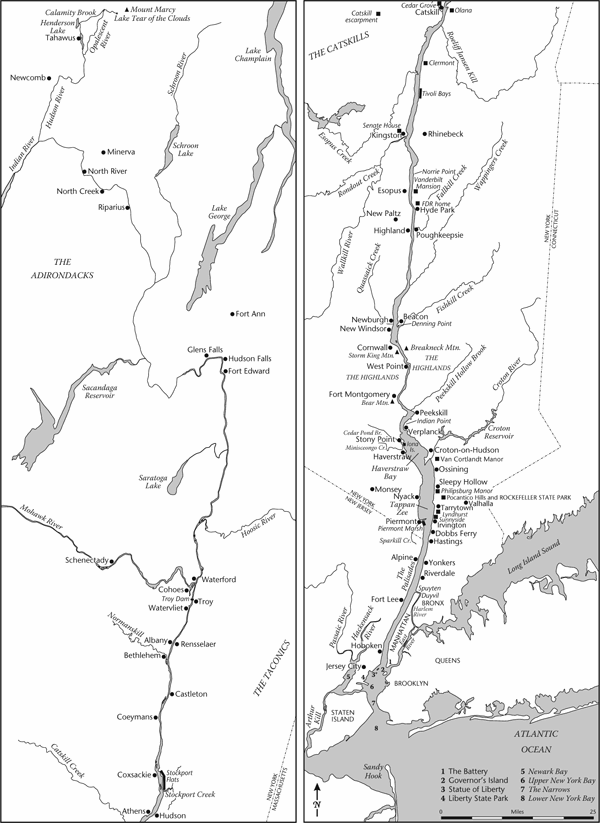

W HEN I WAS a child my father took me and eight or nine of my brothers and sisters white-water rafting near North Forks in the Adirondacks; the water was so clean it tempted me to drink it, but the guides said it was better not to. I thought about that often in the ensuing years, and in 1984, I had the opportunity to do something about it. That year I began working as an attorney for the Hudson River Fishermens Association in Garrison. We worked out of a small farmhouse below Osborns castle in the river stretch between Bear Mountain and Storm King. It was then also that I fell in love with the Hudson Highlands rising in fairy-tale splendor from the rivers banks. The grand homes of the nineteenth-century railroad robber barons seem to nestle in every gully between these sugarloaf peaks. The fishermen operate a patrol boat, the Riverkeeper, which plies the river searching for polluters.

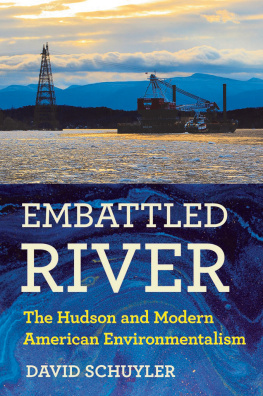

The Hudson is home to one of the most vigilant, sophisticated, and aggressive environmental communities to protect any resource in the world. Since the early 1960s an uncompromising collection of environmental associationsthe Natural Resources Defense Council, the Hudson River Fishermens Association, Clearwater, and Scenic Hudson, to name a fewhave fought to maintain the rivers biological and aesthetic integrity.

Today there is a citizen group at every bend and on both banks ready to do battle with any potential polluter or developer. Many of these battles have ended in victory. Hudson River environmentalists have succeeded in stopping the construction of two major Hudson River highways, two nuclear power plants, and the proposed pumped storage facility on Storm King Mountain. We have forced one utility to create a $17 million endowment for the river and to spend another $20 million to research and build special equipment to avoid fish kills at its power plants. The Hudson River Fishermens Association has brought many polluters to justice. Their willingness to hire lawyers to fight has contributed substantially to our countrys environmental case law. Successful cases against Exxon for its secret water thefts, the Westway project, General Electric for its PCB discharge, Anaconda Wire and Copper for its toxic discharges, and Con Ed for fish kills at its Indian Point Power Plant have created a black letter jurisprudence that forms the foundation of American environmental law. The Hudson River Storm King case is the first case in many environmental law textbooks. That decision gave American environmentalists the standing to sue polluters who injured their aesthetic values. Prior to Storm King, environmentalists could bring actions only where they could prove direct economic damage.

The fight to preserve the rivers viewshed and its astounding biological productivity continues. Once the butt of Tonight Show quips, the Hudson surprisingly is, gallon per gallon, among the planets most productive water bodies. The Hudson is the last estuary on the East Coast of North America and perhaps in the entire North Atlantic drainage that still retains strong spawning stocks of all its historical fish species. I have seen the evidence of this productivity first hand.

Although the Hudson itself is too turbid for good visibility, Ive often gone scuba diving in its tributaries. My favorite is the Croton River, where Ive snorkeled or scuba dived from the rail yard at its mouth upstream to Quaker Rock below the first dam. The pool there is about 12 feet deep during high water in the spring. If I go to the bottom and hug a big rock to stabilize myself in the current, I can sit and watch the pool fill up with fish. Thousands and thousands of alewives or sawbellies come up the Croton on their spawning run from the Atlantic in the early spring. You can see great striped bass that swim up to feed on the herring schools or to spawn. Just above the rail yard the Croton River bottom is carpeted with barnacles. Blue crabs are common during some seasons and you see glass shrimp and other marine invertebrates and crustaceans almost anytime during the spring or summer. Atlantic eels 5 feet long hide between the rocks and in crevices, having migrated from their spawning grounds in the North Atlantic. They feed in the Hudson River for a couple of years and then run back to the Sargasso Sea to spawn. Ravenous schools of snapper bluefish, which I used to catch on Cape Cod as a boy, snatch mayflies in their vicious little teeth, competing with the Crotons abundant trout populationsrainbow, brown, and brook. The freshwater specieslargemouth bass, smallmouth bass, white perch, yellow perch, bluegills, beautiful pumpkinseed sunfish that are as colorful as any of the tropical fish that adorn pet store fish tankscongregate in large numbers in the aerated waters beneath the spillway.

Because of its hydrological connection to the Gulf Stream, tropical fish are common in the estuary. In the Croton, one sees odd creatures like sea horses and a fish called a moongazer, which emits an electric shock when you touch it. Jack Crevalle and Atlantic needlefish, whose home waters are in Florida and the Caribbean, are abundant in the Hudson. Giant carp, weighing 30 to 50 pounds and having the appearance of giant mustachioed goldfish, darken the bottom as they swim overhead in pairs or trios. We also have proper goldfish in the Hudson, though they are less abundant than in former times. They grow extraordinarily largeup to 4 poundsand at least one man, Everett Nack of Claverack, New York, supplemented his income by capturing them for collectors.

The underwater observer is struck by the Hudsons diversity and by its abundance; the impression is of being thrown into a stocked pet store aquarium. Hudson fisherman Tom Lake wrote me that he had caught a permit in the Hudson, the rivers 200th confirmed species. Years ago, I was out with a commercial fisherman under the Tappan Zee Bridge pulling up 10,000 pounds of fish on every lift. The nets were filled with each tide every 6 hours, day and night, week after week, month after month, all springtime. The State Department of Environmental Conservation asked the commercial fishermen to drive their boats slowly in the shallows because at high speeds they were hitting so many fish. In spring the fishermen pulled their nets early because the bountiful striped bass fouled their nets, making it unprofitable to fish for shad. Striped bass from the Hudson cannot be sold, because they are contaminated with PCBs.

Because of its relative diversity, health, and abundance, the Hudson is the Noahs Ark of the East Coast and perhaps of the entire North Atlantic. As the great estuaries of the North Atlanticthe Chesapeake, the St. Lawrence, the Sea of Isov, the Rhine, Long Island Sound, Narragansett Bay, and the Carolina estuariesdecline, the Hudson grows in importance. It is the gene poolthe last safe harbor for species that face extinction elsewhere.

The Hudsons defenders have won many battles to save the river, but ironically, our success on the Hudson has increased the rivers allure to developers and industry. The most challenging fights are yet to come. The big challenge to the Hudsons viability today comes not from a single giant project but the death of a thousand cuts, the decline of the river as condominiums occupy every available piece of shoreline.

Next page